National Grammar Day Generates a Conversation on Insider Jokes

In case you missed it—and you probably did unless you are an English nerd like me—National Grammar Day was March 4th. It came to my attention a few years ago, perhaps because I was teaching an Advanced Grammar class (as I am also doing this year). The “holiday” began in 2008, so it is relatively short on tradition. Martha Brockenborough started the tradition rolling because she felt deeply about proper grammar—this prompted her to start the Society for the Promotion of Good Grammar (SPROGG) and institute National Grammar Day as March 4 (March forth—an imperative). The society has its own website, though posts to it seem few and far between.

As an English nerd, I have tried to take this day and society seriously; however, a quick look at the established website and its posts make that extremely difficult. Most of the posts demonstrate the ways in which “poor” grammar can create unintended humor. See for yourself:

Instead of the proper respect and seriousness, what National Grammar Day did prompt was some semi-serious thought concerning the nature of insider humor and what work such humor actually performs. Grammar jokes belong to one of a great many “niche” jokes—that is, they require that a listener or reader know something about the subject matter in order to appreciate the humor. Mathematics jokes fall into this category of insider humor, as do jokes from other disciplines such as chemistry, engineering, and physics.

Some jokes are universal. Example: Passing gas in almost any situation outside a bathroom—and only private bathrooms at that—seems to provoke universal laughter. These and other slapstick jokes usually do not require insider knowledge in order to tickle the funny bone. Grammar jokes proliferate on the Internet and have always been present as texts even before the Information Superhighway. They are simply easier to access now. Not all of these require as much insider knowledge as some other disciplines because native speakers of English can recognize anomalous errors of Standard English that form the joke. Thus the insider group is relatively large: anyone who has English language proficiency. Yet for the student/scholar of English, the jokes have a richer meaning. For example:

Play and Purpose: Teaching Humor in Introductory Literature Courses

When I am asked to teach a new course, I often revert back to my coaching days. I approach its purpose and structure with all the seriousness and lofty intentions of an English Premier League (EPL) manager. As in soccer, I feel the pressure and necessity of a solid performance. Prior to kickoff, I spent many a late night watching films, meeting with those who held superior knowledge of the game, reviewing formation and dependable goal scorers. All in all, I thought I created a well-researched, slam-dunk course. (Please pardon my mixed sports metaphor – this is my first post – and I am currently suffering from a case of the recently diagnosed DB – dissertation brain.) This semester, as head of an introduction to literary genres team, with humor as my reliable captain, I wanted my students and my course not only to be good, but great. Ryan Giggs great. Or, for those of you less-than-enthusiastic fans, Cristiano Ronaldo great.

Pedagogically, I wanted to build an historical context and contemporary appreciation for my freshman students through an introduction to various types of humor, including farce, satire, dark comedy, parody, slapstick and screwball humor. In our first few meetings, I lectured a bit, and we watched various YouTube videos, SNL skits, and The Daily Show segments, which afforded them comical examples and repartees.

Classic Three Stooges video

Huffington Post’s List of 25 Best SNL Commercial Parodies of All Time

and Salon.com’s 10 Best Segments from Stewart and Colbert:

We read articles on humor, its theories, and laughter’s physiological benefits (see Wilkins and Eisenbraum’s abstract). I was trying to convince my students of humor’s merit, of its historical purpose and value in our modern daily lives. For many reasons, I felt protective of humor, and I wanted them to take the study of it seriously.

In order to accomplish this goal, as well as my course objectives, I stacked my team. My strikers right out of the gate were Swift and Twain. Behind them were O’Henry, O’Connor, Thurber, and Stewart. Two newcomers, Gionfriddo and Alexie, provided necessary depth to my defense. I believed that with the right combination of gentle guidance and direct instruction, my students would grasp the dichotomous nature of my course: play and purpose. While I wanted to set a mutually understood context for laughter, (necessary, I believe, for them to ‘get’ the jokes), I deeply desired for them to see the author’s purpose behind the chuckle: to question and critique social structures and ideology imbedded into America’s framework, as well as their own lives. For the first two weeks of the course, my game plan failed. I had spent so much time trying to force them to understand the legitimacy of humor that I had overlooked the aspect of playing with the language, the situations posed to us by various readings.

Sunday Stand Up: George Carlin’s “Seven Dirty Words”

Tracy Wuster

Today, May 12th, would have been George Carlin’s birthday. Born in 1937, Carlin was one of the key figures of the stand-up renaissance of the 1960s and 1970s. Carlin is listed as #2 on the Comedy Central list of the 100 most influential comedians of all time and was awarded the Mark Twain Prize in American Humor.

“Seven Dirty Words” originated on Carlin’s 1972 album, Class Clown, and was revisited on 1973’s, Occupation: Foole. Carlin was arrested on July 21, 1972 for performing the routine in Milwaukie. The case was dismissed when Carlin’s routine was judged indecent, not obscene. Carlin’s explication of the words led to a court case that eventually ended at the Supreme Court in Federal Communications Commission vs. Pacifica Foundation—a decision that is a modern touchstone in the debate over obscenity (here is part of the FCC transcript of Carlin’s monologue).

Every once in a while, I try to think what those seven words are–can you think of them?

In the Archives: “Yankeeana” from the London and Westminster Review (1838)

Tracy Wuster

Much of the writing on the subject of “American humor” in the nineteenth century–when the idea of a distinctly American humor took shape–came from British critics writing in British journals on the subject of “American Humour.”

Whereas American literature, philosophy, and theology had largely been imitative of European models, British critics consistently saw American “humour” as a new development in American national literature. American humor was increasingly framed as a worthwhile expression of American national life, in addition to being a product that the British reading public consumed with increasing eagerness. American humor expressed important aspects of American life: the scale and grandness of the land through exaggeration, the democratic variety of people through its diversity, and the immaturity of the country and its people through its exuberance and occasional profanity. To use a popular critical metaphor, the British saw humor as a national growth of a young nation, the first literary fruits of the national soil.

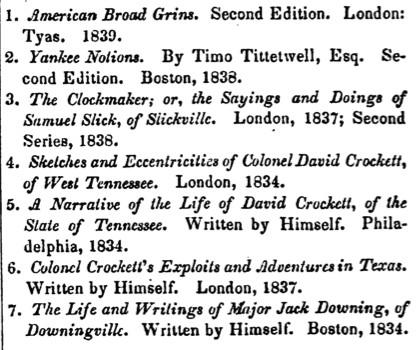

One of the first major critical assessments of American Humour can be found in John Robertson’s “Yankeeana” from The Westminster Review of December 1838 (reprinted in The Museum of Foreign Literature, Science, and Art, Vol. VII, January to April 1839 in Philadelphia). Printed under the initials W.H., this piece examined the works of the following humorists:

This argument is based on the critical assumption that humor as a genre was national in expression, that “it is impregnated with the convictions, customs, and associations of a nation.” American humor expressed the conditions of the people, a list that included: institutions, laws, customs, characters, scenery, Democracy, forests, freedom, universal suffrage, bear-hunts, Puritans, the American revolution, and the “influence of the soil and the social manners of the time.” Such peculiar characteristics of a nation infuse themselves into men, who express the national character through their literature—starting with humor.

Although it takes the author awhile to get to his point, give it some time. Here is the text, in full:

These books show that American literature has ceased to be exclusively imitative. A few writers have appeared in the United States, who instead of being European and English in their styles of thought and diction, [these writers] are American—who, therefore, produce original sounds of far-off echoes,—fresh and vigorous pictures instead of comparatively idealess copies. A portion of American literature has become national and original, and, naturally enough, this portion of it is that which in all countries is always most national and original—because made more than any other by the collective mind of the nation—the humorous.

We have many things to say on national humour, very few of which we can say on the present occasion. But two or three words we must pass on the heresies which abound in the present state of critical opinion on the subject of national humour: we say critical, and not public, for, thank God, the former has very little to do with the latter.

“Lord Byron,”–says William Hazlitt, in a very agreeable and suggestive volume of ‘Sketches and Essays,’ now first collected by his son,–“was in the habit of railing at the spirit of our good old comedy, and of abusing Shakspeare’s Clowns and Fools, which he said, the refinement of the French and Italian stage would not endure, and which only our grossness and puerile taste could tolerate. In this I agree with him; and it is pat to my purpose. I flatter myself that we are almost the only people who understand and relish nonsense.” This is the excuse for the humour of Shakspeare, his rich and genuine English humour!

In Lord Byron the taste which the above opinion expresses is easily accounted for; it was the consequences of his having early formed himself according to the Pope and Gifford school, which was the dominant one among the Cambridge students of his time. Scottish highland scenery, and European travel, aided by the influences of the revival of a more vigorous and natural taste in the public, made his poems much better than the taste of the narrow school to which he belonged could ever have made them; but above the dicta of his school his critical judgment never rose. We thought the matter more inexplicable as regards William Hazlitt, a man superior to Byron in force and acuteness of understanding–until we found the following declaration of his views:–“In fact, I am very much of the opinion of that old Scotch gentleman who owned that ‘he preferred the dullest book he had ever read to the most brilliant conversation it had ever been his lot to hear.’ ” A man to whom the study of books was so much and the study of men so little as this, could not possibly understand the humour of Shakspeare’s Clowns and Fools, or national humour of any sort. The characters of a Trinculo, or Bardolph, a Quickley, or a Silence, are matters beyond him. That man was never born whose genuine talk, let it be as dull as it may, and whose character, if studied aright, is not pregnant with thoughts, deep and immortal thoughts, enough to fill many books. A man is a volume stored all over with thoughts and meanings, as deep and great as God. A book, even when it contains the “life’s blood of an immortal spirit,” still is not an immortal spirit, not a God-created form. Wofully fast will be his growth in ignorance who prefers reading books to reading men. But the time-honoured critical journals have critics–

“The earth hath bubbles as the waters hath”–

and William Hazlitt, with his eloquent vehemence, was one of the best of them.

The public have of late, by the appreciation of the genuine English humour of Mr. Dickens, shown that the days when the refinement which revises Shakspeare and ascribes the toleration of his humour to grossness and puerility of taste, or relish for nonsense, have long gone by. The next good sign is the appreciation of the humour of the Americans, in all its peculiar and unmitigated nationality. Humour is national when it is impregnated with the convictions, customs, and associations of a nation. What these, in the case of America, are, we thus indicated in a former number:–“The Americans are a democratic people; a people without poor; without rich; with a ‘far-west’ behind them; so situated as to be in no danger of aggression from without; sprung mostly from the Puritans; speaking the language of a foreign country; with no established church; with no endowment for the support of a learned class; with boundless facilities for “raising themselves in the world;” and where a large family is a fortune. They are English men who are all well off; who never were conquered; who never had feudalism on their soil; and who, instead of having the manners of society determined by a Royal court in all essential imitative to the present hour of that of Louis the Fourteenth of France had them formed, more or less, by the stern influences of Puritanism.

National American humour must be all this transformed into shapes which produce laughter. The humour of a people is their institutions, laws, customs, manners, habits, characters, convictions,—their scenery, whether of the sea, the city, or the hills,—expressed in the language of the ludicrous, uttering themselves in the tones of genuine and heartfelt mirth. Democracy and the ‘far-west’ made Colonel Crockett: he is a product of forests, freedom, universal suffrage, and bear-hunts. The Puritans and the American revolution, joined to the influence of the soil and the social manners of the time, have all contributed to the production of the character of Sam Slick. The institutions and scenery, the convictions and the habits of a people, become enwrought into their thoughts, and of course their merry, as well as their serious thoughts. In America, at present, accidents of steamboats are extremely common, and have therefore a place in the mind of every American. Hence we are told that, when asked whether he was seriously injured by the explosion of the boiler of the St. Leonard steamer, Major N. replied that he was so used to be blown-up by his wife, that a mere steamer had no effect upon him. In another instance laughter is produced out of the very cataracts which form so noble a feature in American scenery. The captain of a Kentucky steam-boat praises his vessel thus:—”She trots off like a horse—all boiler—full pressure—it’s hard work to hold her in at the wharfs and landings. I could run her up a cataract. She draws eight inches of water—goes at three knots a minute—and jumps all the snags and sand-banks.” The Falls of Niagara themselves become redolent with humour. “Sam Patch was a great diver, and the last dive he took was off the Falls of Niagara, and he was never heard of agin till t’other day, when Captain Enoch Wentworth, of the Susy Ann whaler, saw him in the South Sea. ‘Why,’ says Captain Enoch to him—’why, Sam,’ says he, ‘how on airth did you get here, I thought you was drowned at the Canadian lines.’—’Why,’ says Sam, ‘I didn’t get on earth here at all, but I came slap through it. In that are Niagara dive I went so everlasting deep, I thought it was just as short to come up t’other side, so out I came on these parts. If I don’t take the shine off the sea-serpent, when I get back to Boston, then my name’s not Sam Patch.'”

The curiosity of the public regarding the peculiar nature of American humour, seems to have been very easily satisfied with the application of the all-sufficing word exaggeration. We have, in a former number, (‘London and Westminster Review’ for January 1838, p. 266.) sufficiently disposed of exaggeration, as an explanation of the ludicrous. Extravagance is a characteristic of American humour, though very far from being a peculiarity of it; and, when a New York paper, speaking of hot weather, says:—”We must go somewhere—we are dissolving daily—so are our neighbours.—It was rumoured yesterday, that three large ridges of fat, found on the side-walk in Wall street, were caused by Thad. Phelps, Harry Ward, and Tom Van Pine, passing that way a short time before:—the humour does not consist in the exaggeration that the heat is actually dissolving people daily—a common-place at which no one would laugh—but in the representation of these respectable citizens as producing ridges of fat. It is humour, and not wit, on account of the infusion of character and locality into it. The man who put his umbrella into bed and himself stood up in the corner, and the man who was so tall that he required to go up a ladder to shave himself, with all their brethren, are not humorous and ludicrous because their peculiarities are exaggerated, but because the umbrella and the man change places, and because a man by reason of his tallness is supposed too short to reach himself.

The cause of laughter is the ascription to objects of qualities or the representations of objects or persons with qualities the opposite of their own:—Humour is this ascription or representation when impregnated with character, whether individual or national.

It is not at all needful that we should illustrate at length by extracts the general remarks we have made, since the extensive circulation and notice which American humour has of late obtained in England have impressed its general features on almost all minds. But we may recall them more vividly to the reader, and connect them more evidently with the causes in which they originate, by showing very briefly how institutions infuse themselves into men, how the peculiarities of the nation re-appear in the individual, and how, in short, the elements of the society of the United States are ludicrously combined and modified in the characters, real and fictitious, of Sam Slick, Colonel Crockett, and Major Jack Downing.

Sam Slick is described as “a tall thin man, with hollow cheeks and bright twinkling black eyes, mounted on a good bay horse, something out of condition. He had a dialect too rich to be mistaken as genuine Yankee.” His clothes were well made and of good materials, but looked as if their owner had shrunk since they were made for him. A large brooch and some superfluous seals and gold keys, which ornamented his outward man, looked “New England” like. “A visit to the States had, perhaps, I thought” —says the traveller, who describes him, as he fell in with him on the road—”turned this Colchester beau into a Yankee fop.” The traveller at one time thought him a lawyer, at another a Methodist preacher, but on the whole was very much puzzled what to make of him. Sam Slick turns out to be an exceedingly shrewd and amusing fellow, who swims prosperously through the world by means of “soft sawder” and “human natur.” Ho is a go-ahead man, convinced that the Slicks are the best of Yankees, the Yankees the best of the Americans, and the Americans are generally allowed to be the finest people in the world. He is an enthusiast in railroads. Of the “gals” of Rhode Island he says they, beat the Eyetalians by a long chalk—they sing so high some on ’em they go clear out o’ hearin, like a lark. When a man gets married, he says, his wife “larns him how vinegar is made—Put plenty of sugar into the water aforehand, my dear, says she, if you want to make it real sharp.” The reader will recognise several of the peculiarities of American society in “Setting up for Governor:”—

” ‘I never see one of them queer little old-fashioned teapots, like that are in the cupboard of Marm Pngwash,’ said the Clockmaker, ‘that I don’t think of Lawyer Crowningshield and his wife. When I was down to Rhode Island last, I spent an evening with them. After I had been there a while, the black househelp brought in a little home-made dipt candle, stuck in a turnip sliced in two, to make it stand straight, and set it down on the table.’—’Why,’ says the Lawyer to his wife, ‘Increase, my dear, what on earth is the meaning o’ that? What does little Viney mean by bringin in such a light as this, that aint ftt for even a log hut of one of our free and enlightened citizens away down east; where’s the lamp?’—’My dear,’ says she, ‘I ordered it—you know they are a goin to set you up for Governor next year, and I allot we must economise or we will be ruined—the salary is only four hundred dollars a year, you know, and you’ll have to give up your practice—we cah’t afford nothin now.’

“Well, when tea was brought in, there was a little wee china teapot, that held about the matter of half a pint or so, and cups and sarcers about the bigness of children’s toys. When he seed that, he grew most peskily ryled, his under lip curled down like a peach leaf that’s got a worm in it, and he stripped his teeth, and showed his grinders like a bull-dog. ‘What foolery is this?’ said he.—’My dear,’ said she, ‘it’s the foolery of being Governor; if you choose to sacrifice all your comfort to being the first rung in the ladder, don’t blame me for it. I didn’t nominate you—I had not art nor part in it. It was cooked up at that are Convention, at Town Hall.’ Well, he sot for some time without sayin a word, lookin as black as a thunder cloud, just ready to make all natur crack agin. At last he gets up, and walks round behind his wife’s chair, and takin her face between his two hands, he turns it up and gives her a buss that went off like a pistol—it fairly made my mouth water to see him; thinks I, them lips aint a bad bank to deposit one’s spare kisses in, neither. ‘Increase, my dear,’ said he, ‘I believe you are half right, I’ll decline to-morrow, I’ll have nothin to do with it—I won’t be a Governor on no account.

“Well, she had to haw and gee like, both a little, afore she could get her head out of his hands; and then she said, ‘Zachariah,’ says she, ‘how you do act, aint you ashamed? Do for gracious sake behave yourself:’ and she coloured up all over like a crimson piany; ‘if you havn’t foozled all my hair, too, that’s a fact,’ says she; and she put her curls to rights, and looked as pleased as fun, though poutin all the time, and walked right out of the room. Presently in come two well-dressed house-helps, one with a splendid gilt lamp, a real London touch, and another with a tea tray, with a large solid silver coffee-pot, and tea-pot, and a cream jug, and sugar bowl, of the same genuine metal, and a most an elegant set of real gilt china. Then in came Marm Crowingshield herself, lookin as proud as if she would not call the President her cousin; and she gave the Lawer a look, as much as to say, I guess when Mr. Slick is gone I’ll pay you off that are kiss with interest, you dear you—I’ll answer a bill at sight for it, I will, you may depend.

“‘I believe,’ said he, ‘agin, you are right, Increase, my dear, its an expensive kind of honour that bein Governor, and no great thanks neither; great cry and little wool, all talk and no cider—its enough I guess for a man to govern his own family, aint it, dear?'”

Of Colonel Crockett we shall not say one word further than to direct the attention of our readers to a passage which they may have seen before, but which they will not regret seeing again, so full is it of meanings regarding both the man and the influences by which he was made what he was. The humours of an English election are somewhat different from those described by Crockett, and he evidently knows little of anything like the loyal affection which the electors of the mother country have for “her Majesty’s likeness in gold.”

“I met with three candidates for the Legislature; a Doctor Butler, who was, by marriage, a nephew to General Jackson, a Major Lynn, and a Mr. McEver, all first-rate men. We all took a horn together, and some person present said to me, ‘Crockett, you must offer for the Legislature.’ I told him I lived at least forty miles from any white settlement, and had no thought of becoming a candidate at that time. So we all parted, and I and my little boy went on home.

“It was about a week or two after this, that a man came to my house, and told me I was a candidate. I told him not so. But he took out a newspaper from his pocket, and show’d me where I was announced. I said to my wife that this was all a burlesque on me, but I was determined to make it cost the man who had put it there at least the value of the printing, and of the fun he wanted at my expense. So I hired a young man to work in my place on my farm, and turned out myself electioneering. I hadn’t been out long before I found the people began to talk very much about the bearhunter, the man from the cane; and the three gentlemen, who I have already named, soon found it necassary to enter into an agreement to have a sort of caucus at their March court, to determine which of them was the strongest, and the other two was to withdraw and support him. As the court came on, each one of them spread himself, to secure the nomination; but it fell on Dr. Butler, and the rest backed out. The doctor was a clever fellow, and I have often said he was the most talented man I ever run against for any office. His being related to Gen’l. Jackson also helped him on very much; but I was in for it, and I was determined to push ahead and go through, or stick. Their meeting was held in Madison county, which was the strongest in the representative district, which was composed of eleven counties, and they seemed bent on having the member from there.

“At this time Colonel Alexander was a candidate for Congress, and attending one of his public meetings one day, I walked to where he was treating the people, and he gave me an introduction to several of his acquaintances, and informed them that I was out electioneering. In a little time my competitor, Doctor Butler, came along; he passed me without noticing me, and I suppose, indeed, he did not recognise me. But I hailed him, as I was for all sorts of fun; and when he turned to me, I said to him, ‘Well, doctor, I suppose they have weighed you out to me; but I should ltke to know why they fixed your election for March instead of August? This is,’ said I, ‘a branfire new way of doing business, if a caucus is to make a representative for the people!’ He then discovered who I was, and cried out ‘D—n it, Crockett, is that you?’—’Be sure it is,’ said I, ‘but I don’t want it understood that I have come electioneering. I have just crept out of the cane, to see what discoveries I could make among the white folks.’ I told him that when I set out electioneering I would go prepared to put every man on as good footing when I left him as I found him on. I would, theretore, have me a large buckskin hunting-shirt made, with a couple of pockets holding about a peck each; and that in one I would carry a great big twist of tobacco, and in the other my bottle of liquor; for I knowed when I met a man and offered him a dram, he would throw out the quid of tobacco to take one, and after he had taken his horn, I would out with my twist, and give him another chaw. And in this way he would not be worse off than when I found him; and I would be sure to leave him in a first-rate good-humour. He said I could beat him electioneering all hollow. I told him I would give him better evidence of that before August, notwithstanding he had many advantages over me, and particularly in the way of money; but I told him that I would go on the products of the country; that I had industrious children, and the best of coon dogs, and they would hunt overy night till midnight to support my election; and when the coon fur wa’n’t good I would myself go a wolfing, and shoot down a wolf, and skin his head, and his scalp would be good to me for three dollars, in our state treasury money; and in this way I would get along on the big string. He stood like he was both amused and astonished, and the whole crowd was in a roar of laughter. From this place I returned home, leaving the people in a first-rate way; and I was sure I would do a good business among them. At any rate I was determined to stand up to my lick-log, salt or no salt.

“In a short time there came out two other candidates, a Mr. Shaw and a Mr. Brown. We all ran the race through; and when the election was over, it turned out that I beat them all by a majority of two hundred and forty-seven votes, and was again returned as a member of the Legislature from a new region of the country, without losing a session. This reminded me of the old saying—’A fool for luck, and a poor man for children.'”

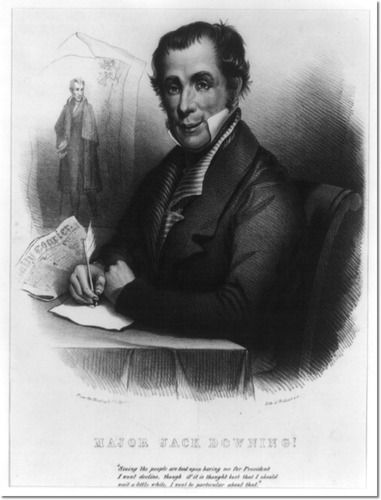

Major Jack Downing is, like Sam Slick, a fictitious character, while Crockett, though now dead, was a real one. But in the letters of Major Jack Downing, there is reality enough to show that they express much that is highly characteristic of America. Here is a caricature of some of the toils of a President.

“I cant stop to tell you in this letter how we got along to Philadelphy, though we had a pretty easy time some of the way in the steam-boats. And I cant stop to tell you of half the fine things I have seen here. They took us up into a great hall this morning as big as a meeting-house, and then the folks begun to pour in by thousands to shake hands with the President; federalists and all, it made no difference. There was such a stream of ’em coming in that the hall was full in a few minutes, and it was so jammed up round the door that they could’nt get out again if they were to die. So they had to knock out some of the windows and go out t’other way.

“The President shook hands with all his might an hour or two, till he got so tired he could’nt hardly stand it. I took hold and shook for him once in awhile to help him along, but at last he got so tired he had to lay down on a soft bench covered with cloth and shake as well as he could, and when he could’nt shake he’d nod to ’em as they come along. And at last he got so beat out, he couldn’t only wrinkle his forard and wink. Then I kind of stood behind him and reached my arm oand under his, and shook for him for about a half an hour as tight as I could spring. Then we concluded it was best to adjourn for to-day.”

In the following passage, with which we conclude, there is some playful banter on the present President of the United States.

“But you see the trouble ont was, there was some difficulty between I and Mr. Van Buren. Some how or other Mr. Van Buren always looked kind of jealous at me all the time after he met us at New York; and I couldn’t help minding every time the folks hollered ‘hoorah for Major Downing’ he would turn as red as a blaze of fire. And wherever he stopped to take a bite or to have a chat, he would always work it, if he could, somehow or other so as to crowd in between me and the President. Well, ye see, I wouldn’t mind much about it, but would jest step round ‘tother side. And though I say it myself, the folks would look at me, let me be on which side I would; and after they’d cried hoorah for the President, they’d most always sing out ‘hoorah for Major Downing.’ Mr. Van Buren kept growing more and more fidgety till we got to Concord. And there we had a room full of sturdy old democrats of New Hampshire, and after they all had flocked round the old President and shook hands with him, he happened to introduce me to some of ’em before he did Mr. Van Buren. At that the fat was all in the fire. Mr. Van Buren wheeled about and marched out of the room looking as though he could bite a board nail off. The President had to send for him three times before he could get him back into the room again. And when he did come, he didn’t speak to me for the whole evening. However we kept it from the company pretty much; but when we come to go up to bed that night, wo had a real quarrel. It was nothing but jaw, jaw, the whole night. Mr. Woodbury and Mr. Cass tried to pacify us all they could, but it was all in vain, we didn’t one of us get a wink of sleep, and shouldn’t if the night had lasted a fortnight. Mr. Van Buren said the President had dishonoured the country by placing a military Major on half-pay before the second officer of the government. The President begged him to consider that I was a very particular friend of his; that I had been a great help to him at both ends of the country; that I had kept the British out of Madawaska away down in Maine, and had marched my company clear from Downingville to Washington, on my way to South Carolina, to put down the nullifiers; and he thought I was entitled to as much respect as any man in the country.

“This nettled Mr. Van Buren peskily.—He said he thought it was a fine time of day if a raw jockey from an obscure village away down east, jest because he had a Major’s commission, was going to throw the Vice President of the United States and the heads of Departments into the back ground. At this my dander began to rise, and I stepped right up to him, and says I, Mr. Van Buren, you are the last man that ought to call me a jockey. And if you’ll go to Downingville and stand up before my company with Sargeant Joel at their head, and call Downingville an obscure village, I’ll let you use my head for a foot-hall as long as you live afterwards. For if they wouldn’t blow you into ten thousand atoms, I’ll never guess again. We got so high at last that the old President hopt off the bed like a boy; for he had laid down to rest him, bein it was near daylight though he couldn’t get to sleep.”

H.W.

[1] John Robertson, “Yankeeana.” The Westminster Review (December 1838). Quoted in The Museum of Foreign Literature, Science, and Art, vol. VII—New Series (Philadelphia: E. Littell & Co., 1839), 75-6.

In the Archives: Ambrose Bierce, “Wit and Humor” (1911)

Tracy Wuster, In the Archives

While Ambrose Bierce was considered, during his lifetime (and since), as an American humorists, he has been hard to fit into a general schema of American humor. Bierce doesn’t make it into Constance Rourke’s American Humor: A Study of National Character, maybe because he was opposed to the common man and the writer of dialect that figures so prominently in Rourke’s view of American humor. As Blair and Hill point out in America’s Humor, Bierce was a wit whose pen functioned as a scalpel often aimed at the common man and colloquial speech, presaging a movement toward wit and urbanity, toward alienation and fantasy, away from the native soil of 19th century humor. Interestingly, Bierce’s views on humor do not seem to have gotten much attention from humor studies scholars.

In The Devil’s Dictionary (1906), his attitude toward the humorist becomes clear:

HUMORIST, n. A plague that would have softened down the hoar austerity of Pharaoh’s heart and persuaded him to dismiss Israel with his best wishes, cat-quick.

Lo! the poor humorist, whose tortured mind

See jokes in crowds, though still to gloom inclined—

Whose simple appetite, untaught to stray,

His brains, renewed by night, consumes by day.

He thinks, admitted to an equal sty,

A graceful hog would bear his company.Alexander Poke

SATIRE, n. An obsolete kind of literary composition in which the vices and follies of the author’s enemies were expounded with imperfect tenderness. In this country satire never had more than a sickly and uncertain existence, for the soul of it is wit, wherein we are dolefully deficient, the humor that we mistake for it, like all humor, being tolerant and sympathetic. Moreover, although Americans are “endowed by their Creator” with abundant vice and folly, it is not generally known that these are reprehensible qualities, wherefore the satirist is popularly regarded as a soul-spirited knave, and his ever victim’s outcry for codefendants evokes a national assent.

Hail Satire! be thy praises ever sung

In the dead language of a mummy’s tongue,

For thou thyself art dead, and damned as well—

Thy spirit (usefully employed) in Hell.

Had it been such as consecrates the Bible

Thou hadst not perished by the law of libel.Barney Stims

WIT, n. The salt with which the American humorist spoils his intellectual cookery by leaving it out.

Bierce seems to have written sparsely about humor and wit directly in his voluminous writings. One piece, though, is of special note in the discussion of wit and humor. Published in The Collected Works of Ambrose Bierce, Vol. X: The Opinionator (1911), the essay “Wit and Humor” may have been a revision of “Concerning Wit and Humor” from the San Francisco Examiner (from either or both June 26, 1892 and March 23, 1903; 12).

His essay on “Wit and Humor,” obviously sides with the wit–not that there are any in America. Like many essays on humor in the nineteenth century (see Hazlitt or Lowell or Repplier, for examples) the distinction between wit and humor is central for Beirce, but unlike those others, Bierce is willing to more clearly distinguish between the two, and his essay is shorter and more readable than many. Interesting that the piece is not regularly, or so far as I can tell, ever reprinted in collections on humor. Enjoy

****

(98)

Wit and Humor

If without the faculty of observation one could acquire a thorough knowledge of literature, the art of literature, one would be astonished to learn “by report divine” how few professional writers can distinguish between one kind of writing and another. The difference between description and narration, that between a thought and a feeling, between poetry and verse, and so forth–all this is commonly imperfectly understood, even by most of those who work fairly well by intuition.

The ignorance of this sort that is most general is that of the distinction between wit and humor, albeit a thousand times expounded by impartial observers having neither. Now, it will be found that, as a rule, a shoemaker knows calfskin from sole-leather and a blacksmith can tell you wherein forging a clevis differs from shoeing a horse. He will tell you that it is his business to know such things, so he knows them. Equally and manifestly (99) it is a writer’s business to know the difference between one kind of writing and another kind, but to writers generally that advantage seems to be denied: they deny it to themselves.

I was once asked by a rather famous author why we laugh at wit. I replied: “We don’t–at least those of us who understand it do not.” Wit may make us smile, or make us wince, but laughter–that is the cheaper price that we pay for an inferior entertainment, namely, humor. There are persons who will laugh at anything at which they think they are expected to laugh. Having been taught that anything funny is witty, these benighted persons naturally think that anything witty is funny.

Hello, I Must Be Going: The Musicianship of the Marx Brothers

Few artists create something so wholly original that they themselves become their own genre. This is certainly true of the Marx Brothers. The family of Jewish immigrant entertainers came from the vaudeville stage tradition – which included sight gags, one-liners, and musical and dance numbers – yet the brothers remain utterly unique, even among the vast variety inherent in vaudeville. There is a certain serendipity in these geniuses developing their craft at a pivotal moment in emerging media. The Marx Brothers were able to perfectly bridge an old-fashioned stage routine with the relatively newer medium of talking film, bringing an otherwise antiquated form of entertainment into the modern age seamlessly.

Few artists create something so wholly original that they themselves become their own genre. This is certainly true of the Marx Brothers. The family of Jewish immigrant entertainers came from the vaudeville stage tradition – which included sight gags, one-liners, and musical and dance numbers – yet the brothers remain utterly unique, even among the vast variety inherent in vaudeville. There is a certain serendipity in these geniuses developing their craft at a pivotal moment in emerging media. The Marx Brothers were able to perfectly bridge an old-fashioned stage routine with the relatively newer medium of talking film, bringing an otherwise antiquated form of entertainment into the modern age seamlessly.

Part of their genius lies in their audacity, and it is the manic chaos they created that keeps their work from becoming dated. The films were made mostly in the 1930’s and 1940’s although, other than the occasional plot device, the gags are almost sui generis, entirely detached from any current outside events or influences. By creating these exaggerated characters, and playing them consistently in each film, they create their own world, which can be picked up and dropped into any time and any place. This creates a timelessness to their work and is the reason the films still play just as well today as ever. Part of this success was the fortuitous timing of talking films, but only these four brothers possessed the right kind of mad genius and grounded talent to have seized upon it so well.

The brothers were essentially born into show business, and were each musical from the start. In fact, their original act (including brother Gummo, who soon quit to fight in World War I) was primarily a musical one. Billed, in various incarnations, as The Four Nightingales or The Six Mascots, they played theaters, concert halls and other venues throughout the country as a vocal group. In response to audience behavior and events outside one particular venue Groucho began to incorporate off the cuff one-liners into their act, which immediately became more popular with audiences than the act itself. Eventually, the brothers morphed from a musical act with occasional comedy into a comedy act with occasional music. The Marx Brothers formula as we now know it was born, as was the classic line-up of Groucho, Chico, Harpo and Zeppo.

Musical numbers remained a constant element of the formula. Groucho was an accomplished guitarist, studying the instrument for most of his life. But Groucho’s contribution to the musical numbers in the films was mostly as a comedic vocalist. He did not demonstrate the flashy virtuosity of Chico’s piano or Harpo’s harp, but his numbers became centerpieces of the films and some of the most memorable moments.

Two of his best-known numbers appear as a medley in 1930’s Animal Crackers, where Groucho plays the famed Captain Geoffrey T. Spaulding.

One morning I shot an elephant in my pajamas. How he got in my pajamas I don’t know.

“Hello, I Must Be Going” and “Hooray For Captain Spaulding” create a mock grand musical number complete with company chorus that heralds the arrival and celebrates the exploits of the famed African explorer. As always, Groucho’s unique dance moves are as graceful as they are ridiculous.

This fact I emphasize with stress,

I never take a drink unless –

Somebody’s buying…

I hate a dirty joke I do

Unless it’s told by someone who –

Knows how to tell it.

The Harold Arlen and Yip Harburg penned “Lydia, the Tattooed Lady” from 1939’s At the Circus became one of Groucho’s signature songs, and one which he continued to sing for the remainder of his life at appearances. (The occasional songwriting team of Arlen and Harburg wrote several songs together, most notably “Over the Rainbow.”) Continue reading →

Seeking: New Contributing Editors/Best Political Humor of the Season

Tracy Wuster

We here at Humor in America are seeking to add one or two contributing editors to replace several departing editors. The task of an editor is fairly straightforward: contribute content once per month on an area of humor studies. Our departing editors work in the fields of visual humor and stand-up, but we are open to adding solid work in almost any area of humor studies.

You will be scheduled to post a piece once per month, although I am extremely flexible about scheduling. The goal is to make your work for the site useful for your own academic interests and valuable to our readers. If you are interested, please contact Tracy Wuster at wustert@gmail.com. If you have expressed interest before, please do so again to remind us of who you are and let us know you still might be interest.

For more information, see our “Write for Us!” page, and feel free to ask questions.

****

In other news, we have an open slot for a day shortly before the election, and I was hoping to post a sampling of the best political humor of the political season. What I need from you is an email with nominations–what humor (cartoons, TV satire, internet meme, video, commentary, joke, tweet, etc.) was your favorite or was most interesting in how humor and politics interact. Please email me at: wustert@gmail.com

In the meantime, here is one nomination, from Joss Whedon, on Romney and Zombies:

Thanks.

Voter ID Laws and the Question of Political Satire

Tracy Wuster

Most of the time, politics is a serious business. People tend to take the government fairly seriously–our laws, our government, our rights. True, traditionally Congress has been an object of fun, and politicians–from Abraham Lincoln to Sarah Palin–have been the butt of jokes. But the importance of political humor–from parody to cartoons to satire–might best be seen as a reflection of how seriously people take politics.

In this highly political year, I have been very interested in questions of how political humor functions in American society. Recently, I discussed the satire of the RNC and DNC conventions on the Daily Show. Similarly, Self Deprecate’s contributions to our site and his site have tackled the current state of political humor.

One political issue that I have been increasingly concerned with this year is distinctly not funny: voter suppression. While proponents of voter ID and other voting laws argue that voter fraud is a real issue (apart from their clownish attempts to prove voter fraud by committing voter fraud), critics of these laws have argued that they are better explained as politically motivated efforts to suppress the votes of people of color, the poor, and the elderly. As John Dean argued in a blog post entitled, “The Republican’s Shameless War on Voting“:

There is absolutely no question that Republicans are trying to suppress non-whites from voting, throughout the Southern states, in an effort that has been accelerating since 2010. It is not difficult to catalogue this abusive Republican mission, which unfortunately has spread, in a few instances, to states above the Mason-Dixon Line as well.

Other stories back up this argument:

Harold Meyerson on the Washington Post

Charles Blow in the New York Times

Recent developments in voter laws in Texas, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and other states also testify to the seriousness of this issue. Those with any historical sense hear echoes of past efforts to restrict suffrage for political gain and based on cultural prejudice. Serious stuff.

Where does the humor come in?

Let’s start with Gary Trudeau’s “Doonesbury” strip from July 23 of this year:

And from the next day:

And check out the rest of the series: here, here, here , and ending with this one:

But that wasn’t all…