An interview with Chris Gilbert, author of “Caricature and National Character: The United States at War”

Want to order the book? Here is a discount code: ZOOM40

Tell me about your start in humor studies. How and when did you begin pursuing it as a subject? who or what has influenced you as a scholar of humor?

In some ways, my “study” of humor began at a very early age. I like comics as a kid. I also really liked television cartoons—The Simpsons, of course, but also shows like Pinky and the Brain and The Ren & Stimpy Show when I was fairly young, and then South Park and Family Guy when I was in high school. And I was a huge fan of The Far Sidecomic strip and the magazines MAD and Cracked. You can most certainly see these influences on some of the things I have written about as an academic—MAD, for one example unrelated to my book, as well as the obvious: editorial cartoons. But these influences were there, too, in my interests as an undergrad and in my decision to more formally start studying the role of humor in public culture, for instance in the comic antics of Kurt Cobain. I wrote my undergraduate thesis on Cobain for a course in rhetorical criticism, and focused my attention on how he used humor in interviews and public appearances and concerts to disrupt his celebrity and throw wrenches in the spokes of the corporate system of music production and hero—never mind anti-hero—worship.

I also wrote about the humor behind Hunter S. Thompson’s so-called Gonzo journalism, in addition to the comic artworks of Thompson’s longtime collaborator, the British caricature artist and illustrator, Ralph Steadman. I should also note that I’ve always dabbled in pen-and-ink drawings myself. In grade school and then again in middle school, I was known as the kid who could draw. That reputation has stuck to this day, with both friends and family members asking me whether or not I drew the picture of Uncle Sam by Francis Gilbert Atwood for my book when they first saw the cover. All of this is to say that a deep immersion in various things that can be seen as comically artful and, by extension, humorous paved the way for the intellectual pursuits that have motivated me since I was a burgeoning academic.

Tell me about the genesis and creation of this project. What questions did you set out to answer, and how did your project develop to answer them?

The initial impetus for this project grew out of my fascination with the extent to which editorial cartoons have long served so many rhetorical purposes in U.S. American wartimes. Since the Founding Period, they have been used for propaganda, military recruitment, criticism, and so on. What I realized more and more, though, as I looked into editorial cartoons in specific moments of both armed conflict and political crisis (which, in our history, often go together) is that they are frequently at the center of images and ideas about cultural identity. Consider Ben Franklin’s early artwork that dabbled in depictions of something like national union in his appeal to join or die.

Consider Thomas Nast, an Irish immigrant, in the Civil War era making caricatures of Americanism with a nationalistic kind of liberalism that pushed him toward the heart of principles that we all like to say are part and parcel of who we are. Liberty. Freedom. Opportunity. And consider that Nast’s work over and again appealed to the better angels of civic virtue as they come up against the vices, and even the violent spasms and paroxysms, that emanate from our political differences, i.e., xenophobia, racism, sexism, and other forms of prejudice that undermine—or, sadly, underwrite—collective pride.

Then there’s the collection of editorial cartoons about American Empire at the turn of the twentieth century and their mockeries of our emerging war machine as an arsenal of democracy unto itself that swelled during the two world wars. I could go on with references to the Cold War and the post-9/11 milieu and the rhetorical mire of our present moment, making connections between notions that the might of militarism blends with the righteousness of presumed manifest destiny. Suffice it to say, though, that in this entire complex history is a certain comic spirit that imbues caricatures of American cultural identity, and thereby national character, from war posters through reflections on cultural warfare in comic illustrations to revilements of warism and its collateral damages in editorial cartoons. Quite simply, I wanted to know why, in addition to how this trajectory of wartime caricature lends a powerful and dynamic endurance to comicality in our national character.

.

Your book—Caricature and National Character—focuses on how political cartoons during times of war help us understand American character. Can you give us an example that demonstrates your approach?

It is so hard not to point you to the cover of my book since the image there encapsulates what might be seen less as either a democratic or an imperialistic leap of faith, propelled by a war mentality, than a leap of foolishness. That’s what caricature captures, in a rhetorical sense: combinations of wisdom and folly, sense and nonsense. That Uncle Sam is blindfolded further betrays a sort of metaphor for caricature as a means of making comic imagery into a looking glass for our ways of seeing—and our ways of not seeing.

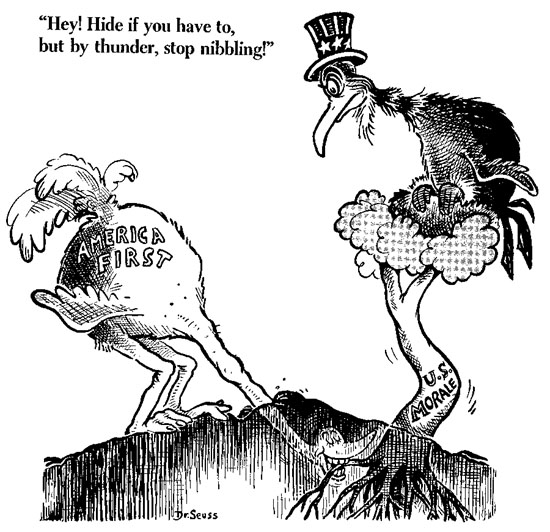

To say that the U.S. or any other nation has something like a “national character” is to suggest that we need to see ourselves in particular ways through the lenses of our historical principles and peculiar institutions. It is to imagine ways of being as they are impelled by ways of seeing various points of shared identification that exist, however blatantly or flagrantly or latently, in our collective consciousness. Such a comic imagination carries through every chapter of Caricature and National Character. We see it in the view of citizens at arms in Flagg’s “I Want YOU!” poster. We see it in Dr. Seuss’s image of an ostrich with its head in the sand. We see it in Ollie Harrington’s goad for us to look at who we are through the eyes of children. We see it in Telnaes’ entire framework for reimagining the prideful arrogance of a democratic nation that—much like the Uncle Sam that fills out the cover of my book—is on its way toward the Fall, precipitating the death of democracy on the precipice of a people’s own making.

I guess what I am getting at here is that my combination of cultural critique and rhetorical analysis relies on an assemblage of caricatures that grapple with ways of seeing how national character gets represented and recast for the sake of comic judgment. Variations on persistent themes matter a great deal here, which is why no single image will do.

.

What influence do you hope your book might have on conversations in humor studies? In other fields?

One hope is simply that readers either revisit or rethink editorial cartoons! They are still very much alive and, well, animated in our public culture.

I also hope that Caricature and National Character provokes renewed conversations about editorial cartoons, and caricature more broadly, in terms of public communication that is usually considered to be so utterly time-bound and so utterly topical that it is misrepresented as something to be seen once and then set aside. It is a fairly conventional perception that editorial cartoons provide a quick jolt or a laugh, but then give way to other modes of understanding around what is going on in the world. They are usually only conferred special purchase when they are controversial. A central element of my argument in this book as that caricatures in editorial cartoons and other comic illustrations are extraordinary precisely because of how ordinary they are in the conveyance of what matters to bodies politics both at specific moments in history and across the annals.

Then there is the aspect of caricature that goes beyond any discernible sense of humor. Perhaps scholars and other readers will look at the rhetorical force of caricature not just vis-à-vis human folly in the comic sense but also in terms of the hardline, hard-nosed, hard-hearted, and even fanatical ideologies that more than ever seem to lead so many of us to look at other people as little more than strangers and enemies in our midst. Along these lines, I would be delighted to discover that Caricature and National Character urges us to recognize that humor can certainly be used to preach to the choir, that it can constructively be used to sustain what Jim Caron dubs a “comic public sphere,” but that it can also be used, if not misused, to promote festive styles of hatred and crude carnivals of—to borrow a phrase from Hunter S. Thompson—fear and loathing. This latter dimension of humor requires our attention.

Finally, it is my sincere hope that scholars in other fields and readers beyond those interested in humor per se might turn to some of the arguments I make in this book to work out the variety of ways in which warism is baked into our official politics, our media cultures, our images and ideas about how to (in a weirdly Wilsonian way) keep the world safe for democracy. On the scholarly front, I wonder what people will think about where to go with comic imaginations if we are to turn toward rhetorical means of protecting and defending democratic institutions without recourse to the wiles of political officials or the soft powers of strong states. In more lay terms, I wonder what we might do to take pause with caricatures that situate our perspectives and opinions and beliefs on the comic edge of a distorted mirror that doubles as the oddly, distortedly, yet no less picture-perfect portrayal.

.

What trends do you see (or wish you saw) in humor studies? What do you hope for the future of the field?

There is such a rich tradition in humor studies of scholars really showcasing that which is humorous, comical, comedic, and the like, and doing so in a way that more often than not demonstrates the unique value that these modalities bestow upon humanity. I say this because I came to humor studies with an honest sense that others in the intellectual community shared my sense of just how vital what we study is to any understanding of everything from the progenation of rhetoric (let alone philosophy) through the establishment of so many societal divisions between upper and lower, sacred and profane, civil and brutish, etc. to the everyday dealings of human beings as homo ridens. I say this, too, because my hope for the future of humor studies is that it will continue on its trajectory of garnering more and more attention, more and more scholarly respect, and more and more acclaim as a site for dynamic academic inquiry.

Still, I do think there is even greater room for humor at the heart of cultural studies and rhetorical analysis. These days, perhaps more than ever, that which is humorous, comical, comedic, and the like is problematic—and I mean this in the Foucaultian or Deleuzean sense that something needs to be problematized—in that these things need to be subjected to new questions about why they are important, why they are relevant, and even why they are at issue with conventional ideas regarding what makes, say, this or that iteration of humor humorous, or even what makes humorhumor, and then again how we understand it as “good” or “bad” or somewhere in between. Some of the best scholarship on humor is not caught up in definitional or conceptual hairsplitting—at least not solely. Rather, it is tied to matters of politics, identity, communication, justice, judgment, and more. People are looking differently, for instance, at the comic spirits in activism and outreach that persist to deal with some of the darkest aspects of the human condition, i.e., racial bigotry. I and others are re-imagining the relationship between pleasure and pain as it is manifest in things like satiric films and stand-up comedy acts. I and others are also rethinking comedies of human survival in the face of literal catastrophe. This includes earthly devastations with regard to climates and species. It includes cultural crises such as racism, gun violence, and political divisions that traverse the boundaries of life on the streets, so to speak, and the policy measures that stem from seats of government. I can only imagine that humor studies will see redoubled efforts by scholars to connect their subjects and objects of interest to these all too real circumstances of life and death.

.

What’s next for you?

It feels a little strange to start talking about a second book just months after my first book was published, especially because I want to honor the work I did and the energy I expended to put the ideas of Caricature and National Character out into the world. But I have a hard time sitting still, and so am already in the initial stages of developing a new manuscript. It is very much in keeping with what I just mentioned about problematizing studies of humor, and it will be about what I am characterizing as instances when comedy goes wrong. The project will have a historical angle. However, it will be more focused on recent times than Caricature and National Character, which has its origin stories in the years leading up to and then carrying on from the First World War. Beyond the second book, I have a number of side projects in progress as well as a feeling that some rest and relaxation might serve me well in the waning days of summer! Nevertheless, as I often suggest when I sign off: more soon.

Laughing with Laugh Tracks

Teaching American Humor: Laughing with Laugh Tracks

My life would be better with a laugh track. My writing would be better, too. So would your reading experience–well, with a laugh track and a few drinks…

I am with the majority opinion on this issue, at least according to most producers of American situation comedies for the last sixty years. The reasoning behind the laugh track, as I see it, goes like this: A laugh track makes people laugh; people who laugh enjoy situation comedies; people who enjoy situation comedies see plenty of commercials; people who see commercials while in a good mood tend to buy things; a laugh track makes people laugh, and so on… Those who buy and sell commercials fund sitcoms, and they have never been inclined to trust writers or audiences. Neither do I.

I have skillfully written two first-rate jokes thus far. But, of course, you can’t really know that because this post does not have a laugh track. I spent several hours trying to insert laugh track audio here and failed. That’s funny–I think–but how can any of us be sure?

Teaching the American sitcom requires some discussion of laugh tracks. I admit that I have only glossed over laugh tracks in courses on American humor thus far. This has been a mistake. I have awakened to an obvious point: laugh tracks provide a compelling way for students to consider a more challenging array of characteristics of the art form–from the aesthetic to the mundane, from the heart of performance to the mechanics of production, from the implicit honesty of comedy to the manipulative potential of technology. From now on, I will begin all coursework focused on the sitcom with the laugh track.

Here is how I came to this astounding awakening; it’s all about The Big Bang Theory. I like the show (though I can’t decide whether I should consider it a “guilty pleasure” or an appreciation of solid, if broad, writing). The laugh track, however, drives me crazy. It is loud and intrusive. I don’t believe it at all. I am not alone. Any quick Google search of “laugh tracks” will provide over 31,000,000 hits. Type in “Big Bang Theory,” and you will find 127,000,000 hits, virtually all of which refer to the show (I didn’t check out all of them, by the way. I simply reached that conclusion using the scientific method based on my observations of the first two pages). Here is a fact: lots of people care about the television show; almost nobody cares about the scientific theory. A search of the show title combined with “laugh tracks” gets 181,000 hits. Lots of people hate the laugh track (lots of people hate the show, too). YouTube has plenty of clips of the show with the laugh track removed. Here are two examples:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PmLQaTcViOA

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ASZ8Hks4gko

These clips draw out two basic responses from interested parties: one, that the show is hurt by the laugh track (so the complaint concerns its use rather than the inherent quality of the show itself); two, that the laugh track lamely attempts to cover up a lousy show. There is no reconciling of these opposing positions, but the removal of the laugh track is disingenuous in that it creates a show wherein the comedic timing has been wholly distorted. The Big Bang Theory is filmed in front of a live audience, and the performance reflects the interaction between audience and cast. The producers of the show claim that the audience responses are genuine and have not been “sweetened,” a term to imply that the laughter has been engineered in production to enhance audience responses. This claim is disingenuous as well. Any production process will inevitably “sweeten” the final product–from placement of microphones to volume applied. All steps in the process of preparing a show for airing are a form of “sweetening.” Simply because the producers do not use canned laughter (laughter recordings NOT from an live audience) does not mean that no laughter manipulation occurs. Of course it does. As always, The Onion provides the best satirical take on laugh tracks with the show by simply raising the volume of the laugh track so that it wholly overpowers the show itself: Big Bang Theory with laugh track enhanced by The Onion

John Oliver, FIFA, American Humor, and Topic Sentences

John Oliver got rid of Sepp Blatter. That would be a bold statement if I cared at all about Sepp Blatter or FIFA. I do not. I do care, however, about John Oliver, my favorite funny person from Great Britain (currently; it is a long list). More importantly, for this venue, is the contribution that John Oliver with his work on Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (HBO) is making to American humor. As one who has been distraught over the loss of The Colbert Report and the impending departure of Jon Stewart from The Daily Show, I have been worried that we were facing the end of a golden age in American television political and social satire. I think it will last a bit longer, and I am sure that John Oliver is key to its future.

John Oliver got rid of Sepp Blatter. That would be a bold statement if I cared at all about Sepp Blatter or FIFA. I do not. I do care, however, about John Oliver, my favorite funny person from Great Britain (currently; it is a long list). More importantly, for this venue, is the contribution that John Oliver with his work on Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (HBO) is making to American humor. As one who has been distraught over the loss of The Colbert Report and the impending departure of Jon Stewart from The Daily Show, I have been worried that we were facing the end of a golden age in American television political and social satire. I think it will last a bit longer, and I am sure that John Oliver is key to its future.

The Nightly Show with Larry Wilmore is solid, and Trevor Noah may prove to reinvigorate the Daily Show, so my worries may be overblown. It is Last Week Tonight, however, that holds the most promise. Quite simply, it transforms the basic formula codified by The Daily Show under Jon Stewart (and applied to a specific parodic context by Colbert) and makes it decidedly more argumentative. Last Week Tonight is thesis-driven humor, which marks a dramatic shift in ambition, or, perhaps, confidence. In either case, Oliver will not admit it.

Oliver is nonetheless catching fire. On a recent appearance on CBS This Morning , Charlie Rose asked one question that seemed clear and concise (if you can believe it): “What is the intent of this ‘dumb’ show?” (Oliver had already called it “dumb” based on the introductory clips).

“Just to make people laugh.” OK, John, you get a pass since this is the standard answer for any such discussion of humor. Why a duck? Because ducks are funny, that’s why. But you are lying.

Oliver’s self-deprecation notwithstanding, the fact is that no one in American television has ever put together satirically charged arguments in segments ranging from 12 to 20 minutes (easily 2 to 4 times as long as standard Daily Show bits) that are focused on one issue with such depth and humor. Never. There are easier ways to make people laugh.

In the interview, Oliver would not assert a more elaborate purpose and underplayed any major role for satire itself. As to whether satire served a deeper purpose in his work, he simply said, “I have no idea. Ideally, satire would do no better than anyone.” He went on to explain the show’s long form, weekly approach: “It’s some slow cooking, what we do.”

Yes, slow cooking. It took a year to get Sepp Blatter. That is the pace of satire. C’mon, John, admit it.

To begin a closer look at the Last Week Tonight formula, let’s stick with Blatter and the two episodes that most directly skewer FIFA, the first of which aired on 8 June 2014 and the second on 1 June 2015. A brief look at these two episodes should provide a good indication of the power of Oliver’s thesis-driven comedy and the potential of long-form television satire. Both episodes feature FIFA as the main topic, and each segment runs just over 13 minutes. Here are links to each:

The key to Oliver’s approach could be understood best, perhaps, by considering it as a model for clear, argumentative writing. In fact, I urge all freshman composition instructors in the nation to drop all textbooks and simply use Last Week Tonight to teach the modes of argumentative writing. Let’s consider the most basic element of building effective arguments: Write clear and concise topic sentences. Note the few examples below:

–“FIFA is a comically grotesque organization.” (8 June 2014).

–“There is a certain irony in FIFA setting up any kind of justice system given the scandals that have dogged it over the years.” (8 June 2014).

–“The problem is: all the arrests in the world are going to change nothing as long as Blatter is still there.” (1 June 2015)

–“When your rainy day fund is so big that you’ve got to check it for swimming cartoon ducks, you might not be a non-profit anymore.” (8 June 2014)

–“Peanut butter and jelly are supposed to go together; FIFA and bribery should go together like peanut butter and a child with a deadly nut allergy.” (8 June 2014)

–“That is perfect because hotel sheets are very much like FIFA officials; they really should be clean, but they are actually unspeakably filthy, and deep down everybody knows that.” (1 June 2015)

Note the clarity of the argumentative position in each statement above. They assert positions, all followed by multiple levels of support within the show (follow the links). That, dear readers, is how you build good essays! It is also how to build fresh, ambitious humor.

Cross-Cultural Humor in Central America

I recently escaped the bitter chill of Philadelphia in early March and traveled to Zamorano University (affectionately referred to here as ‘Zamo’), an oasis of warmth situated approximately 45 minutes outside of the capital city of Tegucigalpa, Honduras (or ‘Tegus’ as the locals call it). I was fortunate to be a part of a course studying the language and culture of various groups, ranging in age from children to college students, while traveling. We had the unique opportunity to work with Zamo students on their conversational English through the sharing of ‘dichos’ or proverbs. While translation from Spanish to English often proved difficult, the proverbs presented a way to bridge the language gap. Students had the chance to act out their proverbs, all the while subjecting themselves to the laughter of their fellow Zamo classmates as well as a few giggles from the American students. We also worked with children at REMAR, an orphanage on the outskirts of Zamo. While this trip was momentous in many ways, it was here that I had a humor epiphany.

While there is much research on the understanding of humor through cross-cultural communication in the fields of psychology, sociology, linguistics, and others (Bell, 2002, 2007; Coulson et al., 2006; Hay, 2001; Carrell, 1997), my epiphany came through physical humor, the kind of slapstick we’re accustom to from the likes of Charlie Chaplin or The Three Stooges.

You see, in Honduras, soccer is ingrained into the fabric of everyday life. Boys and girls alike know how to ‘bend it like Beckham’ – seriously. One mention of Mario Martinez’s goal in the 2012 Olympic quarterfinals against Brazil brings nods and smiles to many of the young faces. In case you missed it, take a look:

http://www.businessinsider.com/video-mario-martinez-honduras-brazil-2012-8

At REMAR, the young children place soccer balls at their friends’ feet and emulate the master, volleying the ball between the posts with flawless precision. They then place a ball by my feet, and I cross it through the air and onto the foot of an anxiously awaiting 13-year-old who dreams of playing for FC Barcelona. When they direct me to stand by the goal line and await a pass, I play along. Not only do I miss, but the ball also pops up and hits my face, knocking me to the ground. It is while I am on the ground that I come to a realization: I hear the children laughing. Similarly to the Zamo students’ feelings while acting out their proverbs, I, too, felt a pang of gelotophobia. There existed a major similarity to the classroom activity and the game: slapstick humor, above all else, seems to be universal in cross-cultural communication. We encountered language barriers and a few laughs through the translations, but it was not until the Zamo students acted out the proverbs that a real bond formed between the two groups of students, the native Spanish and English speakers, through laughter. The children at REMAR picked me up and helped to dust me off, all the while laughing and ‘high-fiving’ me for my mishap. They referred to me as ‘Martinez’ for the rest of my time there – a joke – easily translated and understood by all.

Was it our ability to let down our guard, to fumble and be picked up, that made the communication between these diverse groups possible? Is there something in the mishaps of the body that translates better than language? What other types of humor easily translate across cultures? My epiphany, much like my soccer skills, is still under construction, but for now, I’m headed outside to practice.

c 2015 Tara Friedman

American Film Humor in 25 Screenshots, Part 1

It seems to me that the timing is right for an unapologetically mercenary post that plays with both my innate passion for making lists and my desire for starting arguments. This means that this post will be more self-indulgent than usual. –how can that be?

Here is what I propose: a three-part series that argues not for the twenty-five most important American film comedies but, more specifically, the twenty-five most important American film comedy scenes as represented by screenshots. By “important,” I mean “iconic,” “seminal,” “best,” “most hilarious,” “provocative,” or, in other words, “my favorites.” They should be yours, too.

I intend to start with 7 screenshots that indicate essential comedic moments in American film history in this the first of three posts on the topic. I hope to encourage others to chime in with their favorites by commenting on this post and, ideally, including links or files with the screenshots they suggests. I will follow in subsequent posts with the growing list.

For now, the images are not ranked or presented in any order other than my impulses as I think of them or run through my library of screenshots. In the end, I may try to rank them just for the hell of it.

Here are the first seven:

From Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times. In perhaps one of the most iconic moments in film comedy history, the Tramp is consumed by the industrial machine but continues to perform his job. It is a concise but cogent statement of class tensions and the perils of the “factory worker” caught in the cogs of industrialism. It is so iconic that one cannot talk about it without puns and symbolic flourishes. See above.

From Frank Capra’s It Happened One Night. This first appearance of Clark Gable’s torso provides more than the titillation that such a statement implies. The scene is a remarkable and intricate power struggle between two formidable performers in a comedic gem. The scene, the film as a whole for that matter, would go one to influence the romantic comedy formula to this day. If he had only tried a similar approach to Scarlett.

From the Marx Brothers’ Animal Crackers. This is a shot from the big finale scene wherein everybody gets on stage like the closing of a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame awards show–lots of folks on the stage but with only a few who do anything worthwhile. In this case, that is fine because it is the Marx brothers who demand the attention in every scene. This scene demonstrates the wonderful comic interplay between the brothers but also mocks the pretensions of respectable society and the smug coziness of the officer’s advice to the subversive Harpo.

From Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove. This panoramic shot of the big board and the big table captures a more elaborate scene that the other screenshots selected. It is meant to imply the entire sequence of the power brokers at work to save the world–or at least themselves. In short this shot cuts to the core of all American satire by implicating the inherent horror of a star chamber, no matter how comic.

From Mike Nichols’s The Graduate. This is the money shot–well, that sounds wrong. What I mean is that this shot has its own iconic status and provides the core symbol for both the dramatic and comedic aspects of the film. The triangulating power of Mrs. Robinson’s leg, and little big man Benjamin trying to keep up.

From Harold Ramis’s Caddyshack. No apologies for this one. This shot is from arguably the most concise illustration of the American dream at work in the mind of an inherent loser. Yes, Cinderella is the most American of the European fairy tales. He is the working man dreaming of a Masters championship when all he will end up with is more work replacing the flowers he is destroying.

From The Coen Brothers’ Raising Arizona. This shot is a shot within a shot. The McDonnoughs try to record for posterity their new family portrait, complete with their freshly stolen child. “It’s about to pop, honey.” As we say in the business, this is funny.

OK, then.

Please send suggestions for other essential screenshots via comments to this post.

Cracking the Codes of Comedy: On the Anatomy of Jokes, Part 2

Last month I explored the anatomy of jokes by looking simple joke forms, “light-bulb jokes” in particular, in the ongoing context of applying the scientific method to understanding humor. See: Cracking the Codes of Comedy Part 1

Since I named that post “Part 1,” it would seem that I needed to follow up with a “Part 2.” I am a man of my word.

When I made the implied promise to provide a second installment built off of the popularity of the fine book The Humor Code, I expected to finish the book. I have not. That’s on me and in no way a criticism of the book. Things came up.

But I have continued to think about ways to analyze humor in the classroom using simple joke forms. The light bulb joke form still seems to me to be a rather useful joke. It is simple; it is well established in American culture; and it, in a remarkably short space–time and type–can open up a world of cultural relevance.

I discussed in the earlier post several problematic versions of the joke as they employed clear cultural biases that depended directly on choices of audience and targets. That is the approach that I have recently used in the classroom and to interesting results, to my mind.

I used the light bulb joke as a class activity forcing students to read several versions of the a joke, picking their favorite and justifying their choice base on their understanding of humor in general and their own preferences.

First, I should explain that I am fortunate enough to teach at the University of Alabama (“Roll Tide!”–I am contractually obligated to say that). This is important to the set-up for the three versions of the jokes because of my choice of the targets of the jokes: students from Auburn University. No offense intended. Of course, this context can be adapted to any context and help to illustrate the importance of having a target (or victim) of the light bulb joke format, a group at whom the audience is expected to laugh. In a college context, the obvious target group will simply be the peers at the main rival university. For Alabama students, that means Auburn, clear and simple.

The students responded to the jokes online in a group discussion, so their comments were written individually but in full view of classmates and often in response to earlier comments. There were three versions of the joke described in the following way: general; aggressive, and vulgar. I only required students to read and comment on two of the versions to allow those that wanted to avoid the vulgar version to do so with no penalty. I chose to handle to exercise online for the same reason. I simply did not want to tell the vulgar version to a captive audience. The level of vulgarity, I should add, is rather tame when placed in context with material most students encounter and enjoy. Still, that does not mean that the professor needs to tell it to the class directly. “Will this be on the exam?”

I will type the versions here, so those who wish to avoid the vulgar joke can do so as well. I “wrote” all three jokes, but to my mind, I simply drew from obvious choices and did so in an effort to pick three levels of jokes, from the generic to the profane. I wanted students to deal with audience and target issues, especially as to how “laughing at” and “laughing with” contexts form crucial parts of humor as reflective of cultural tensions. However, my jokes unwittingly revealed a more complex discussion regarding joke structure, which I will discuss below. Here they are:

Version One (general):

How many Auburn students does it take to screw in a light bulb?

Four: one to hold the light bulb and three to turn the ladder.

Version Two (aggressive):

How many Auburn students does it take to screw in a light bulb?

Four: one to hold the light bulb and three to turn the cow.

Version Three (vulgar):

How many Auburn students does it take to screw in a light bulb?

None: they want it to be dark when they f**k the cow.

The results were interesting and more nuanced than I had expected. That is a good sign, by the way.

Version One was voted overwhelmingly as the favorite version, which was a complete surprise to me. I figured that students would reject it for its generic nature, too tame and too dull. Not so. It is generic, yes, but its structure is perfect. And that’s the point that they responded to, which surprised me. They enjoyed the simplicity of the joke and that it was universal (as opposed to trite). Furthermore, in a very typical niceness that is common among my students, they preferred a version that they could enjoy without being too mean to Auburn students. In short, they figured because the joke is so benign that they could laugh along with Auburn students without anyone getting their feelings hurt. I should add, however, that this collegiality would not occur during the Iron Bowl, the football game between the two schools that occurs every late November. Things get more complicated in that context. Just listen to sports-talk radio during football season in the South (any day between August and July).

Version Two was the least popular. In fact, it fell completely flat. This response actually ended up being the most instructive part of the exercise. Students rejected the joke for its faulty structure and faulty assumptions. I had written a bad joke. That is not easy for me to admit. But I blew it.

The problem is the cow (it’s always the cow).

As the joke writer, I assumed a clear context that tied cows to Auburn as a “Cow College” (short for a university with a rural location and that has an agriculture program). I also assumed that my University of Alabama students knew of that context and had always seen it for its potential as a point of derision toward Auburn. Auburn, indeed, does have a strong agricultural history, as a land-grant institution that from its inception served agricultural interests in the state. Bama students, however, were mostly bewildered by that context. “What’s up with the cow?” Only after one student made the connection to Auburn being a “cow college,” did the students follow the rationale for the four Auburn students supposedly using a cow to screw in a light bulb. Even so, they never thought it was funny. The reference to Auburn as a “cow college” is simply too dated for them.

Fail. But the failure is more complicated. Even when students became aware of the cow connection, the visual component of the joke remains unclear. So the joke not only misfired due to the weakness of the cow reference but also because the audience could not visualize what the hell was going on in any case. In my mind, the image is clear: one student sits astride the cow, and the others pull and tug at the cow to try to get it to walk in a circle as the rider holds the light bulb as it twists into the socket–“Comic gold, Jerry!” They thus provide the same physical movement as with the ladder version, but their efforts are harder and more ridiculous–dumber.

The presence of the cow in this version is intentionally more aggressive and insinuating than the generic ladder of the first version because of the “cow college” reference and the fact that it shows modern students still tied to a primitive solution (beast of burden) to provide electric light in a modern age. Get it? But none of that matters if the visual is not clearly set up. If the audience cannot “see” the absurdity of the cow in the scene or accept any rationale for it to be there, there is no humor.

Simple jokes are complicated.

Let’s pause for a moment to refer to yet another light bulb joke that implies a very sophisticated reference point for its successful punch line.

How many existentialists does it take to change a light bulb?

Two. One to change the light bulb and one to observe how the light bulb symbolizes

an incandescent beacon of subjectivity in a netherworld of Cosmic Nothingness.

I include this here to point out how important common reference points are to successful humor. Although this joke requires some audience awareness of “cosmic nothingness,” the joke itself is no different than the seemingly more simple “cow” reference in my version above. The same rules apply. You have to “see” the light bulb in reference to the cow; or, “see”the light bulb in reference to cosmic nothingness. For a cow to be floating in a netherworld of cosmic nothingness, well, that’s another joke altogether.

The third version had very little support. Some students pointed out something that I had hoped for–that provocative language and vulgarity do have some place in our cultural relationship to simple jokes. Unlike version two, the vulgar version is structurally sound. It is clear and concise, and the profanity as well as the reference to bestiality, carry the power of surprise and conviction. Yes, it is a very aggressive, mean-spirited, and even vicious attack upon the victims of the joke. Still, it is a good joke structurally. But it is not a very funny one the whole once the shock value fades. It is too mean, too clearly desirous of being smugly mean than being cleverly funny. The vulgarity is, as a result, more gratuitous than humorous. I think, also, that students worry about the cow. I worry about it, too.

Light bulb jokes are useful. Student responses to the ones I have employed in class should help us all get ready to move into material that is more delicate as the semester progresses. Being able to see the nuances of social and historical tensions even within the simplest jokes should allow us to examine the structure of a wider variety of jokes and help us assess the complex nature of the codes of comedy. And cows.

A Cow Picture that Offers Some Overdue Dignity to Cows source: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2293053/Cows-really-predict-rain-Scientists-prove-likely-lie-weather-cold.html

What is Funny: Using Surveys in Teaching Humor

Teaching American Humor:

What is funny?

I begin all courses on humor by polling students on their tastes. What do they find funny and why? It is a logical beginning from a pedagogical standpoint because it emphasizes the importance of their voice in the class while also asserting a key point of any study of humor: it’s always personal. Students bring an array of predispositions to the humorous material the course will cover. They know what they like, but they may not be so sure as to WHY they like it. We need to use that tension throughout the course. I must also make sure that while they explore their personal preferences that they also find connections to audiences across time and mediums. In short, they need to recognize that the personal responses also have historical, social, and political connections.

A questionnaire assessing students’ tastes in humor could take any number of forms and approaches, and I would love to hear other ideas. I am certain that many teachers do something very similar to what I am sharing here.

Here are the core questions focused on getting students to open up about their tastes:

**Do you have a good sense of humor?

Obviously, the class will respond overwhelmingly in the affirmative. “YES!!” they shout, “WE HAVE A GREAT SENSE OF HUMOR!” This is true, of course, and I congratulate them on this fine accomplishment. It does, however, set me up for obvious jokes as we discuss their answers to the next two questions wherein they provide examples in support of their good senses of humor.

**List two favorite funny films.

**List two favorite television situation comedies.

There is a wide range of answers to these questions, though they lean very heavy to the most recent hits. For example, The Hangover (1 and 2) has been popular for three semesters in a row, though I am certain that run will be gone by next fall–unless two or three more sequels are released this summer. But it is in no way dominant as a favorite. As for sitcoms, The Big Bang Theory and How I Met Your Mother rank high, but, as with the films, there are no real favorites. This list is broad, with most shows getting only one or two votes (out of 35-40 students).

The wide range is the hoped-for response. It gives us an opportunity to mention quite a few films and shows and seek common ground among the varied responses. The more substantive question follows:

**Judging from your favorite films and sitcoms, how would you define or classify your taste in humor?

This is a key moment in the self-assessment. Students cannot just name a recent familiar title; rather, they have to justify it by defining the attributes that lead to laughter. Here is a rather typical range of the phrases they provide:

–Dry, Witty, Intellectual, Sarcastic

–Vulgar, Unnatural, Tasteless, Crude

–Simple, Physical, Stupid

–Realistic; Relatable

The two largest responses are consistently the first two above, and they are generally equally represented even though they seem contradictory. A significant group of students always values wit above all else. An equally large group values crudity above all else. Some students see themselves in both. The inherent tensions between these two seemingly opposite taste preferences is the crux of the course, perhaps, as students explore the cultural values that encourage–demand–both strains in American humor.

The next question gets to important issues related to how we experience humor:

**Which is funniest scenario? Choose one:

1. –A man slips on a banana peel.

2. –A man who is showing off his skills as a dancer slips on a banana peel.

3. –A man who has just been dumped by his girlfriend slips on a banana peel as he walks away.

The battle for supremacy is waged between answers 2 and 3. A Few students will choose number 1 because they hesitate to admit any pleasure in the pain of others. A man slipping on a banana peel is enough–small harm, small chuckle. When you add in an element of hubris, then the humor potential jumps up exponentially. The guy showing off deserves humbling; that is an easy choice to make. An equal number of students, however, will opt for the other guy in number 3, the one they call “the loser.” What does he deserve? Well, that hardly matters; we simply love someone falling down, the further the better. In all cases, of course, we are all simply thankful that we are not the victim of the vagaries of banana peels and their inexplicable powers for being so damned slippery. It’s a cold world.

The final question ascertaining students’ taste in humor is the easiest one.

**Which is the funnier scenario? Choose one:

–a group of cows

–a group of sheep

Everybody knows that cows are funnier than sheep. Everybody.

Princess Ivona Brings Absurdist Comedy to San Francisco

Many people assess humor and the funny using the same litmus test employed by Justice Potter Stewart in the 1964 obscenity case “Jacobellis v. Ohio.” In regards to hard-core pornography, Stewart famously stated “I know it when I see it.” While I have no knowledge of Justice Stewart’s expertise in this particular subject, I do tend to think that the ability to make snap judgments stems from experience. That is one reason why so many of us feel capable of instantly ascertaining what is funny and what is not. We’ve spent our whole lives laughing, so we believe that we know it when we see it.

Technically speaking, of course, comedy is also a performance structure. (And if you don’t know an academic when you see one, it’s possible to spot a scholar through the use of such phrases as “technically speaking” and “performance structure.”)

I’ve been intimately involved with one particular Absurdist comedy of late, and it’s reminded me of how some of the best comedies question what and how comedy works, and whether we should know comedy when we see it. Last year I joined with some former colleagues from the Stanford and Berkeley doctoral programs in performance to found The Collected Works and our inaugural project is Princess Ivona, a 1935 play by Polish literary legend Witold Gombrowicz. (While the text is European, I trust that staging this in San Francisco qualifies it as “Humor in America.”)

I’ve noticed throughout the production process that Princess Ivona brings to the fore our uneasiness surrounding comedy and our desire to be on the winning side when it comes to mockery and the mocked. On the lower end of the social hierarchy, there are aunts in the first act, concerned that they are being teased…

2nd AUNT: Your Highness is laughing at us of course. You are welcome to, I am sure.

…and courtiers in the second act, determined to tease the court newcomer, only to find that the tables have been turned on them.

2nd LADY: I understand now. You have arranged it all to show us up. What a joke!

Carnival at Court. Image by Jamie Lyons.

The BCS of American College Football Humor

College football has always been funny. From the inherent cartoonish comedy of young men dressed in animal costumes roaming the sidelines (to be clear, I mean the mascots) to the more nuanced ironies and absurdities surrounding conference realignments. How many schools can be in the Big 10? It’s all very funny stuff for a wide range of comedic interests. And all very American.

Many categories and characteristics and contexts of comedy could be offered up as the most definitive of American culture and its traditions, but surely one of the easiest arguments to make would be in support of placing college football at the top of the list. American college football is, well, exceptional. Of course, we would need a computer system in conjunction with votes from academics and comedic performers to be absolutely sure. And it wouldn’t hurt to have some prime locations for conferences to draw in folks for post-semester debates and parades. But I digress. Here is the fact: college football is an American cultural phenomenon as well as an economic and political, pop-cultural juggernaut that has few rivals as a forum and catalyst for American humor year after year. Disappointed in the overall quality and quantity of humor based on and derived from college football this year? Wait until next year! And don’t forget the off-season–just ask Bobby Petrino.

In celebration of the BCS championship game this evening (January 7), I thought I would simply cull together a few exceptional links to humor built around the cultural obsession that is college football. This, at the very least, should suggest many more possible choices, and I hope others will build on this modest beginning.

Let’s start with two examples of the earliest use of football as fodder for physical humor from masters of the art form: The Marx Brothers and The Three Stooges.

The Marx Brothers’ film Horse Feathers (1932) takes on higher education in general as its target of respectability in this film. The plot revolves around corruption of college football via the recruiting of illegal players to win games. Imagine that! Fortunately, such things do not occur anymore, but it was certainly common enough in the 1930s for the Marx Brothers to use it for a running joke (that’s a college football pun).