An interview with Chris Gilbert, author of “Caricature and National Character: The United States at War”

Want to order the book? Here is a discount code: ZOOM40

Tell me about your start in humor studies. How and when did you begin pursuing it as a subject? who or what has influenced you as a scholar of humor?

In some ways, my “study” of humor began at a very early age. I like comics as a kid. I also really liked television cartoons—The Simpsons, of course, but also shows like Pinky and the Brain and The Ren & Stimpy Show when I was fairly young, and then South Park and Family Guy when I was in high school. And I was a huge fan of The Far Sidecomic strip and the magazines MAD and Cracked. You can most certainly see these influences on some of the things I have written about as an academic—MAD, for one example unrelated to my book, as well as the obvious: editorial cartoons. But these influences were there, too, in my interests as an undergrad and in my decision to more formally start studying the role of humor in public culture, for instance in the comic antics of Kurt Cobain. I wrote my undergraduate thesis on Cobain for a course in rhetorical criticism, and focused my attention on how he used humor in interviews and public appearances and concerts to disrupt his celebrity and throw wrenches in the spokes of the corporate system of music production and hero—never mind anti-hero—worship.

I also wrote about the humor behind Hunter S. Thompson’s so-called Gonzo journalism, in addition to the comic artworks of Thompson’s longtime collaborator, the British caricature artist and illustrator, Ralph Steadman. I should also note that I’ve always dabbled in pen-and-ink drawings myself. In grade school and then again in middle school, I was known as the kid who could draw. That reputation has stuck to this day, with both friends and family members asking me whether or not I drew the picture of Uncle Sam by Francis Gilbert Atwood for my book when they first saw the cover. All of this is to say that a deep immersion in various things that can be seen as comically artful and, by extension, humorous paved the way for the intellectual pursuits that have motivated me since I was a burgeoning academic.

Tell me about the genesis and creation of this project. What questions did you set out to answer, and how did your project develop to answer them?

The initial impetus for this project grew out of my fascination with the extent to which editorial cartoons have long served so many rhetorical purposes in U.S. American wartimes. Since the Founding Period, they have been used for propaganda, military recruitment, criticism, and so on. What I realized more and more, though, as I looked into editorial cartoons in specific moments of both armed conflict and political crisis (which, in our history, often go together) is that they are frequently at the center of images and ideas about cultural identity. Consider Ben Franklin’s early artwork that dabbled in depictions of something like national union in his appeal to join or die.

Consider Thomas Nast, an Irish immigrant, in the Civil War era making caricatures of Americanism with a nationalistic kind of liberalism that pushed him toward the heart of principles that we all like to say are part and parcel of who we are. Liberty. Freedom. Opportunity. And consider that Nast’s work over and again appealed to the better angels of civic virtue as they come up against the vices, and even the violent spasms and paroxysms, that emanate from our political differences, i.e., xenophobia, racism, sexism, and other forms of prejudice that undermine—or, sadly, underwrite—collective pride.

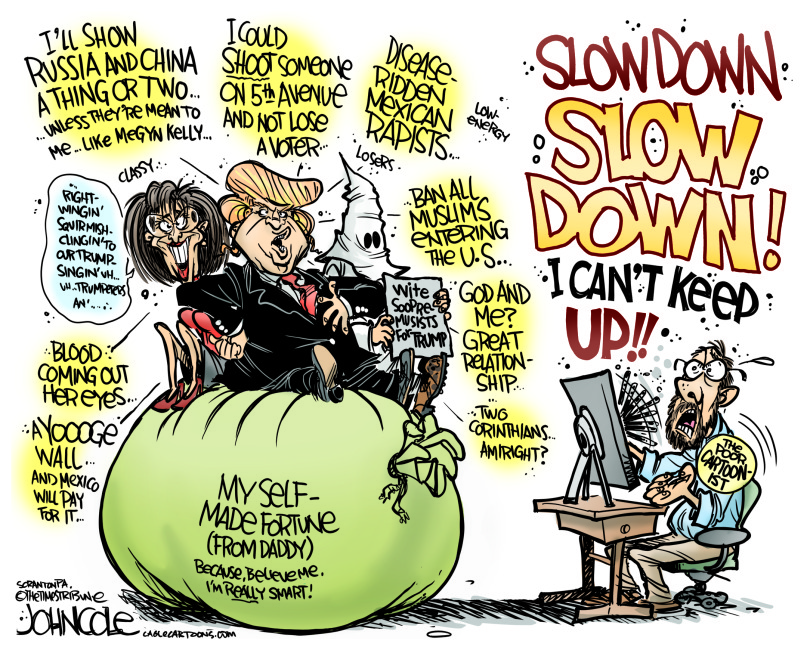

Then there’s the collection of editorial cartoons about American Empire at the turn of the twentieth century and their mockeries of our emerging war machine as an arsenal of democracy unto itself that swelled during the two world wars. I could go on with references to the Cold War and the post-9/11 milieu and the rhetorical mire of our present moment, making connections between notions that the might of militarism blends with the righteousness of presumed manifest destiny. Suffice it to say, though, that in this entire complex history is a certain comic spirit that imbues caricatures of American cultural identity, and thereby national character, from war posters through reflections on cultural warfare in comic illustrations to revilements of warism and its collateral damages in editorial cartoons. Quite simply, I wanted to know why, in addition to how this trajectory of wartime caricature lends a powerful and dynamic endurance to comicality in our national character.

.

Your book—Caricature and National Character—focuses on how political cartoons during times of war help us understand American character. Can you give us an example that demonstrates your approach?

It is so hard not to point you to the cover of my book since the image there encapsulates what might be seen less as either a democratic or an imperialistic leap of faith, propelled by a war mentality, than a leap of foolishness. That’s what caricature captures, in a rhetorical sense: combinations of wisdom and folly, sense and nonsense. That Uncle Sam is blindfolded further betrays a sort of metaphor for caricature as a means of making comic imagery into a looking glass for our ways of seeing—and our ways of not seeing.

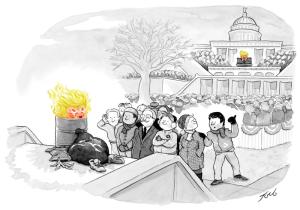

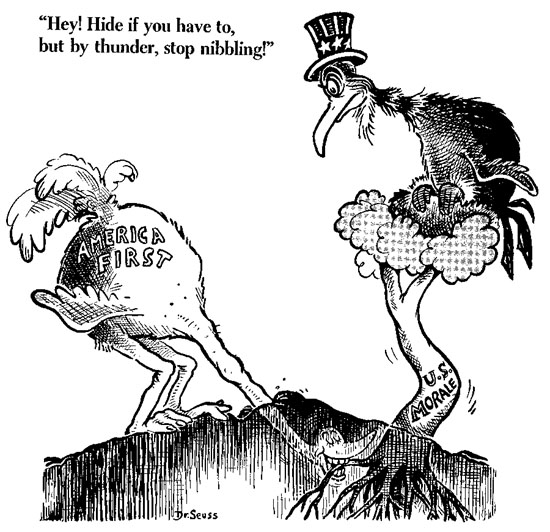

To say that the U.S. or any other nation has something like a “national character” is to suggest that we need to see ourselves in particular ways through the lenses of our historical principles and peculiar institutions. It is to imagine ways of being as they are impelled by ways of seeing various points of shared identification that exist, however blatantly or flagrantly or latently, in our collective consciousness. Such a comic imagination carries through every chapter of Caricature and National Character. We see it in the view of citizens at arms in Flagg’s “I Want YOU!” poster. We see it in Dr. Seuss’s image of an ostrich with its head in the sand. We see it in Ollie Harrington’s goad for us to look at who we are through the eyes of children. We see it in Telnaes’ entire framework for reimagining the prideful arrogance of a democratic nation that—much like the Uncle Sam that fills out the cover of my book—is on its way toward the Fall, precipitating the death of democracy on the precipice of a people’s own making.

I guess what I am getting at here is that my combination of cultural critique and rhetorical analysis relies on an assemblage of caricatures that grapple with ways of seeing how national character gets represented and recast for the sake of comic judgment. Variations on persistent themes matter a great deal here, which is why no single image will do.

.

What influence do you hope your book might have on conversations in humor studies? In other fields?

One hope is simply that readers either revisit or rethink editorial cartoons! They are still very much alive and, well, animated in our public culture.

I also hope that Caricature and National Character provokes renewed conversations about editorial cartoons, and caricature more broadly, in terms of public communication that is usually considered to be so utterly time-bound and so utterly topical that it is misrepresented as something to be seen once and then set aside. It is a fairly conventional perception that editorial cartoons provide a quick jolt or a laugh, but then give way to other modes of understanding around what is going on in the world. They are usually only conferred special purchase when they are controversial. A central element of my argument in this book as that caricatures in editorial cartoons and other comic illustrations are extraordinary precisely because of how ordinary they are in the conveyance of what matters to bodies politics both at specific moments in history and across the annals.

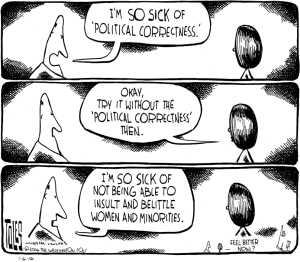

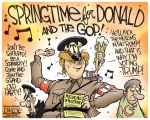

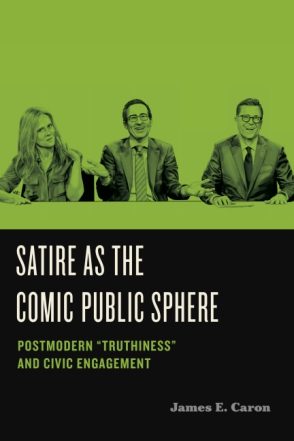

Then there is the aspect of caricature that goes beyond any discernible sense of humor. Perhaps scholars and other readers will look at the rhetorical force of caricature not just vis-à-vis human folly in the comic sense but also in terms of the hardline, hard-nosed, hard-hearted, and even fanatical ideologies that more than ever seem to lead so many of us to look at other people as little more than strangers and enemies in our midst. Along these lines, I would be delighted to discover that Caricature and National Character urges us to recognize that humor can certainly be used to preach to the choir, that it can constructively be used to sustain what Jim Caron dubs a “comic public sphere,” but that it can also be used, if not misused, to promote festive styles of hatred and crude carnivals of—to borrow a phrase from Hunter S. Thompson—fear and loathing. This latter dimension of humor requires our attention.

Finally, it is my sincere hope that scholars in other fields and readers beyond those interested in humor per se might turn to some of the arguments I make in this book to work out the variety of ways in which warism is baked into our official politics, our media cultures, our images and ideas about how to (in a weirdly Wilsonian way) keep the world safe for democracy. On the scholarly front, I wonder what people will think about where to go with comic imaginations if we are to turn toward rhetorical means of protecting and defending democratic institutions without recourse to the wiles of political officials or the soft powers of strong states. In more lay terms, I wonder what we might do to take pause with caricatures that situate our perspectives and opinions and beliefs on the comic edge of a distorted mirror that doubles as the oddly, distortedly, yet no less picture-perfect portrayal.

.

What trends do you see (or wish you saw) in humor studies? What do you hope for the future of the field?

There is such a rich tradition in humor studies of scholars really showcasing that which is humorous, comical, comedic, and the like, and doing so in a way that more often than not demonstrates the unique value that these modalities bestow upon humanity. I say this because I came to humor studies with an honest sense that others in the intellectual community shared my sense of just how vital what we study is to any understanding of everything from the progenation of rhetoric (let alone philosophy) through the establishment of so many societal divisions between upper and lower, sacred and profane, civil and brutish, etc. to the everyday dealings of human beings as homo ridens. I say this, too, because my hope for the future of humor studies is that it will continue on its trajectory of garnering more and more attention, more and more scholarly respect, and more and more acclaim as a site for dynamic academic inquiry.

Still, I do think there is even greater room for humor at the heart of cultural studies and rhetorical analysis. These days, perhaps more than ever, that which is humorous, comical, comedic, and the like is problematic—and I mean this in the Foucaultian or Deleuzean sense that something needs to be problematized—in that these things need to be subjected to new questions about why they are important, why they are relevant, and even why they are at issue with conventional ideas regarding what makes, say, this or that iteration of humor humorous, or even what makes humorhumor, and then again how we understand it as “good” or “bad” or somewhere in between. Some of the best scholarship on humor is not caught up in definitional or conceptual hairsplitting—at least not solely. Rather, it is tied to matters of politics, identity, communication, justice, judgment, and more. People are looking differently, for instance, at the comic spirits in activism and outreach that persist to deal with some of the darkest aspects of the human condition, i.e., racial bigotry. I and others are re-imagining the relationship between pleasure and pain as it is manifest in things like satiric films and stand-up comedy acts. I and others are also rethinking comedies of human survival in the face of literal catastrophe. This includes earthly devastations with regard to climates and species. It includes cultural crises such as racism, gun violence, and political divisions that traverse the boundaries of life on the streets, so to speak, and the policy measures that stem from seats of government. I can only imagine that humor studies will see redoubled efforts by scholars to connect their subjects and objects of interest to these all too real circumstances of life and death.

.

What’s next for you?

It feels a little strange to start talking about a second book just months after my first book was published, especially because I want to honor the work I did and the energy I expended to put the ideas of Caricature and National Character out into the world. But I have a hard time sitting still, and so am already in the initial stages of developing a new manuscript. It is very much in keeping with what I just mentioned about problematizing studies of humor, and it will be about what I am characterizing as instances when comedy goes wrong. The project will have a historical angle. However, it will be more focused on recent times than Caricature and National Character, which has its origin stories in the years leading up to and then carrying on from the First World War. Beyond the second book, I have a number of side projects in progress as well as a feeling that some rest and relaxation might serve me well in the waning days of summer! Nevertheless, as I often suggest when I sign off: more soon.

An interview with Jim Caron, author of Satire as the Comic Public Sphere: Postmodern “Truthiness” and Civic Engagement

Tell us about your start in humor studies. How and when did you begin pursuing it as a subject? who or what has influenced you as a scholar of humor?

My original topic for my dissertation was a folkloric look at the tall tale as a genre, but that morphed into the tall tale as a form in antebellum American comic writing and an influence on Mark Twain. So, in my academic career, I have always been interested in cultural artifacts that make people laugh.

However, the real turning point was being selected in 1989 for a National Endowment for the Humanities summer seminar on humor held at Berkeley and run by an anthropologist, Stanley Brandes. Those six weeks converted me to an interdisciplinary point of view. I spent more time in Kroeber Library (the anthropology collection) than any other library on the campus, mostly being fascinated by ritual clowns in traditional societies (my earlier folklore penchant had turned into an anthropological one). I’ve tried to maintain an interdisciplinary approach ever since.

.

Tell me about the genesis and creation of this project. What questions did you set out to answer, and how did your project develop to answer them?

The first impetus for the book came from submitting a proposal on satire to a projected collection of essays in the MLA teaching series. The proposal was rejected, but my interest in the topic had developed out of my Year’s Work reviews for Studies in American Humor because over the years I had tracked a growing set of publications on satire. Satire in the first decade of the twenty-first century was becoming a hot topic, which meant that for some time prior to writing the book I was immersed in the scholarly conversation about satire.

The second push came from a comment Judith Lee made about an introductory essay I had written for a special issue of StAH on postmodern satire. In the essay, I referred to satire as a special kind of comic speech act, and with her usual perspicacity, Judith said that that idea could be expanded. The foundation work I had done for the rejected proposal was then turned to use for the book, and the introductory essay on postmodern satire became the first draft of parts of the book.

I wanted to understand satire as a postmodern project in some of the artists that I had been faithfully watching on TV or in comedy specials. The entanglement of contemporary satire with the news was always a stimulus to my thinking. I also wanted to address the issues surrounding satire that I had zeroed in on when I wrote the proposal for the MLA collection: satire’s efficacy as a reform agent; satiric intent versus audience uptake; the importance of cultural context for understanding what the satirist intended and what the audience understood. I don’t see how one can tackle satire and not become enmeshed in these issues, and I use the examples in the book to work through them.

.

Your book—Satire as the Comic Public Sphere—develops a new approach to thinking about how satire, especially satire in the current media landscape, might operate. What do you hope that readers take from the book about how to understand satire?

The approach is new in part because I use speech act theory as a heuristic for contemporary examples of satire that play with the news, so I hope others find that tactic useful. The news as a focal point for some satire, however, points to the big claim in the book: that the best way to think about satire since the Enlightenment is to understand its connection to Jürgen Habermas’s concept, the public sphere. Satire parodies the public sphere and functions as its comic supplement. I think that framework makes sense, and I hope it persuades folks. Also, that framework enables understanding that satire functions as comic political speech, not political speech, which is how many scholars treat it. I suspect that there will be lots of resistance to that distinction, so I’ll be interested how it is processed in future scholarship.

The idea of a “truthiness satire” in a postmodern aesthetic provides a way to think about the recent cultural moment in which people, in particular politicians, offer “alternative facts” as competition in the public sphere to evidence and empirical science. Some folks call the resulting situation “post-truth,” but that misunderstands what has happened, implying that no one is interested in the truth any more, or that it can’t be formulated in a meaningful way. That position is essentially a bastardization of postmodern skepticism, which questions transcendental claims for a Truth, but does not doubt that facts exist and should be marshalled in any public sphere debate. I refer to the dismissal of facts and evidence as the “anti-public sphere,” and ridiculing it is the job of truthiness satire. The book is meant to demonstrate the poetics of that ridicule. I also probe the legitimate limits of that ridicule: when does the symbolic violence of satire descend into mere rants or screeds?

Finally, the first part of the book offers an extended definition of satire that is meant to be useful for other cultures besides American and for other time periods besides now. I hope that readers understand the dual goals of the book: one general and not time-specific, the other very time specific.

.

What influence do you hope your book might have on conversations in humor studies? In other fields?

Of course, what I really want is to alter forever the course of scholarly thinking about satire [insert laughter here]. My hope is that the definition worked out in the first part of the book spurs some thinking about satire in general as well as satire’s function in what some call “the project of modernity,” which includes postmodernity.

For the book’s second part, I hope that my examinations of contemporary satirists like Stephen Colbert, Samantha Bee, and John Oliver are persuasive, that demonstrating the dynamic relationship among the discourse of the public sphere, satire as discourse of the comic public sphere, and truthiness as the discourse of the anti-public sphere shows just how and why satire has become so prominent and so important in recent times.

My approach centers on the aesthetics of satire as well as its communicative force in the public sphere, but satire as a cultural artifact has an appeal across disciplines, including rhetorical theory, communication theory, political science and sociology as well as cultural studies, so I hope the book can contribute to conversations in those fields as well as humor studies. That would be in keeping with my original interdisciplinary interest in what makes people laugh.

.

What trends do you see (or wish you saw) in humor studies? What do you hope for the future of the field?

As a contributing editor and associate editor of StAH for about fifteen years, what I’ve seen is a huge and still growing interest in comic artifacts of all sorts by a wide range of disciplines. That has been exciting to witness and to be a part of.

The scholarly trend has moved away from a focus on literary comic artifacts to other media, especially film, TV, and standup. Gender studies and ethnic studies have also been growing in their influence. Earlier historical periods are somewhat overshadowed by examinations of the now and the recent past. The internet beckons as a largely unexplored territory: we are still trying to get a handle on humorous or satiric memes, for example.

I see the study of cultural artifacts that make people laugh as a growth area (to use market terms) for some time to come. The variety of disciplines that are investigating those artifacts is wonderful, and I don’t envision that letting up. There are now several journals devoted exclusively to scholarship on comic artifacts, and I would not be surprised if others showed up in the future. Moreover, there is still much work that can be done in earlier historical periods. Just trying to keep up with recent artistic production will provide work for many scholars as we conduct our various kinds of research across disciplines.

What’s next for you?

I have another book project centered on satire, partly finished. (I seem to be stuck to satire as though it were a tar baby, though I am not complaining.) My research question: what did satire in the US look like before Mark Twain came along and altered everything? There is a long tradition in the scholarship on American humor in the nineteenth century that sees everything through the lens of Mark Twain, and I want to explore another perspective. Mark Twain is like Mount Rainier in Washington state, so dominating the terrain that is it difficult to escape his shadow.

My research in this project centers on the 1850s, and I am happy to say that there is more satire there than is usually discussed, a perfect example of what might still remain to explore in earlier historical contexts. The star of that book will be Sara Willis Parton and her persona Fanny Fern.

Want to hear more? Jim spoke on this panel for the New Book Talks with the AHSA that focused on New Books on Satire.

The Garden of Curses: Down on the Farm with S.J. Perelman and Nathanael West

Joe Gioia

Let me propose that American literary humor, in becoming modern, branched in two during the Great Depression. On one side are absurd, language-driven vignettes, short magazine pieces ranging from whimsical to surreal where the narrator tries to make sense of, or at least describe, a crackpot world. This strand was largely created and mainly defined by S.J. Perelman, whose comic genius engendered two of the Marx Brothers’ best movies, Monkey Business (1931) and Horsefeathers (1932), and a steady stream of brilliant short pieces for (mainly) The New Yorker.

The other branch trades in black comic predicaments of grotesque dysfunction: a ridiculous overabundance of misery, of mental and physical illness and often absurd violence. Laughter here is defensive: relief at seeing something so horrible happen to someone else. This strain was best, and arguably first, articulated by Nathanael West, author of the superb short novels Miss Lonelyhearts (1933) and The Day of the Locust (1939), who was, funny enough, Perelman’s brother-in-law.

In Perelman’s camp we find his older contemporaries, James Thurber and Robert Benchley, neither of whom had the idiomatic snap, that aggrieved brilliance and fine timing, that Perelman gave the form. Woody Allen and David Sedaris are his natural heirs, along with—in the sillier episodes with his oddly-named characters—Thomas Pynchon.

West’s example, heaping outlandish misery upon uncomprehending and helpless characters, has gained more followers: among the most notable being Joseph Heller (whose Catch-22 only gained wide recognition after Perelman praised it), Stanley Elkin, and David Foster Wallace.

And though West’s own work has never quite overcome the cult status given it following his untimely 1940 death, his artistry is now acknowledged, his works collected in a Library of America edition in 1997. The Day of the Locust may still be our best novel about Hollywood, made into a major 1975 film directed by John Schlesinger, starring Donald Sutherland and Karen Black, and creating, in one of its characters, a hopeless dope named Homer Simpson.

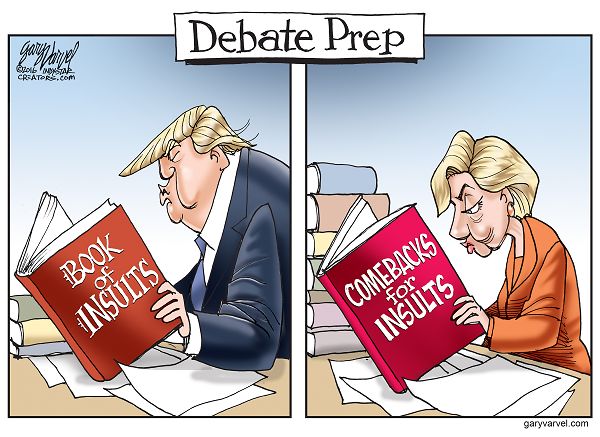

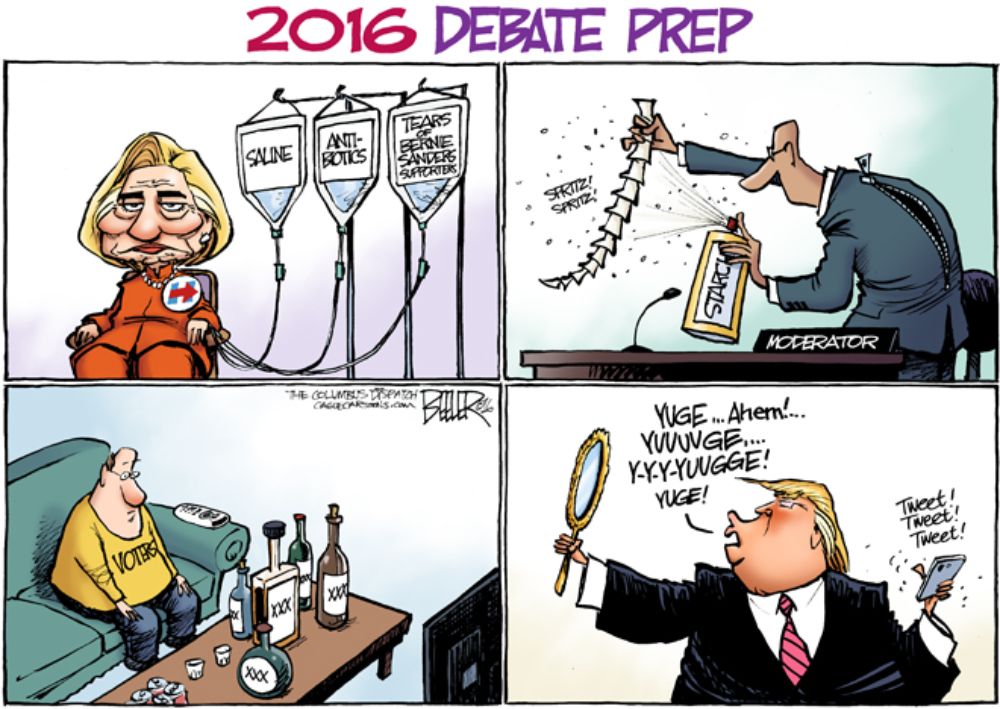

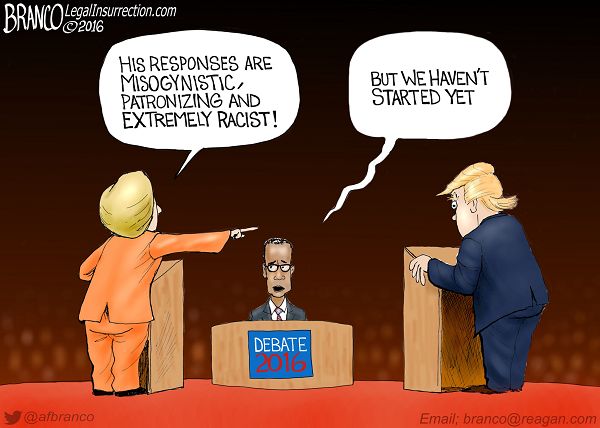

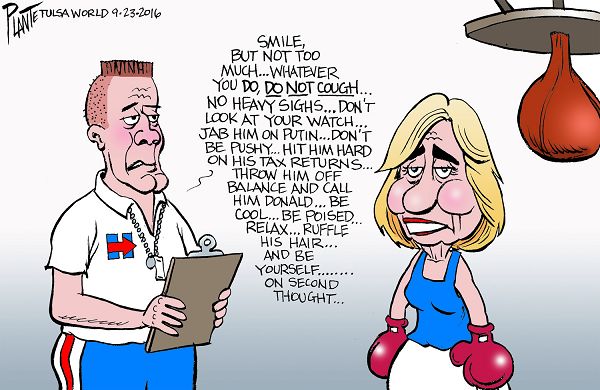

Clinton vs. Trump Debate #1: A Humorous Primer

It’s here. The event of the century. The one we’ve all been waiting for with dread.

A selection of humor to help you prepare:

Trump Planning To Throw Lie About Immigrant Crime Rate Out There Early In Debate To Gauge How Much He Can Get Away With

HEMPSTEAD, NY—Saying he would probably introduce the falsehood in his opening statement or perhaps during his response to the night’s first question, Republican nominee Donald Trump reported Monday he was planning to throw out a blatant lie about the level of crime committed by immigrants early in the first presidential debate to gauge how much he’d be allowed to get away with. More…

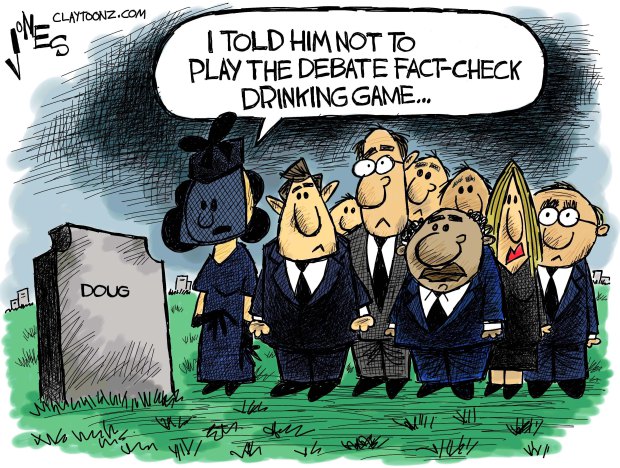

MORE AMERICANS EXPECTED TO SELF-MEDICATE THAN FOR ANY OTHER DEBATE IN HISTORY

With over a hundred million people projected to watch the debate, roughly sixty million of them will be barely sentient after ingesting what they deem to be the necessary dose of intoxicants. More…

Blindfolded Clinton Invites Debate Coaches To Attack Her With Talking Points From All Sides

Standing slightly crouched with her fists raised up in front of her in the middle of her campaign office’s mock stage, a blindfolded Hillary Clinton reportedly implored her high-level staffers to attack her with talking points from all sides Wednesday in preparation for next week’s first presidential debate. More…

TRUMP WARNS THAT CLINTON WILL RIG DEBATE BY USING FACTS

“You just watch, folks,” Trump told supporters in Toledo, Ohio. “Crooked Hillary is going to slip in little facts all night long, and that’s how she’s going to try to rig the thing.” More…

Stay safe out there.

Poll: 89% Of Debate Viewers Tuning In Solely To See Whether Roof Collapses

“Of the 2,000 individuals surveyed, we found that nearly nine in 10 said they would be watching tonight’s debate on the off-chance that they might get to witness the roof of Hofstra University’s Hagedorn Hall suddenly cave in and crush the nominees for president,” said Quinnipiac spokesman Michael Jovan.

Clay Bennett, Chattanooga Times Free Press

Lester Holt Begins Debate By Reminding Audience These The Candidates They Chose

“So, just as a recap: You had numerous options and a full year to decide on the candidates you wanted to be your next president, and these were the two you picked. These two. Right here. All right, now let’s begin.”

Hand-Held Harlequins! : The Super-Humor of DC’s New Girl Powered Action Franchise

“Get your cape on, and let’s take flight! We can be who we like!” – DC Super Hero Girls theme song.

My daughter is a Caped Crusader.

Even in her toddler phase, she always preferred colorful costumes and cataclysmic combat over Barbification or Dora-mania. Yet, as far as we can tell from her second grade peers and pals, she is not a “geek” or a “mean girl.” She’s not a tomboy either, since prim princesses and personified ponies and adamantly American Girls and absolutely anything related to Alex Morgan all fill a good quotient of her 8-year old day. She does quite well in school, just completed her First Communion, plays two sports with aplomb, and has recently survived her first ear piercings, not to mention a fairly brutal soccer-smashed fibula.

Yet, when she really wants to cut loose and get her missy mojo working, she always turns to cosplay. Over the years, she has done turns as Super-girl, Maleficent, Frozen‘s Queen Elsa (Elsa is, ironically, her actual name!) and Leia Organa, but her more recent repertoire includes Batgirl, the Scarlet Witch, the Wasp, and most especially of late, Cat Woman and Agent Carter.

She is hardly alone among her age group in her inclinations toward super-couture, and believe it or not, neither Mom nor I have had much influence on her passionate attraction to wonder-duds. In fact, there isn’t much superhero merch about the house beyond my basement hobbit hole of a Media Studies library. Nor are we a particularly super-duper family, aside from fond memories of the original Super Friends and the occasional spontaneous viewings of The Incredibles or Big Hero 6. For further proof, just ask my 10 year-old son, who completely skipped over all of the superhero genres and contexts that fascinated many of his friends. From his earlest safaris around our home, he has always favored scouts, birding, tennis, and baseball. So super-stuff abides in our lives, but it does not beckon, inundate, or restrict our offspring’s access to other forms of generally pleasant and genuinely good-hearted American middle class fun. Still, on her own time and in her own mind, my daughter is definitely a Super Hero Girl.

Well Trouble’s A Bubble: Dick Van Dyke at 90

Photo by Nicola Buck

Dick Van Dyke celebrated his 90th birthday this past December 13, the way most nonagenarians do – by participating in a flash mob. Fitting for a man whose career is peppered with characters of youthful, childlike vision. In his impressive, 70-plus-year career he’s amassed five Emmys, a Tony and a Grammy.

Van Dyke got his start on radio and quickly moved to the stage. In 1959 he snagged the lead in Bye Bye Birdie, a role he reprised for the 1963 film. Other films followed including Chitty Chitty Bang Bang and Divorce American Style, but it was the 1964 Disney adaptation of Mary Poppins that gave birth to his most remembered film roll, as Bert the chimney sweep. Continue reading →

One Sided Scholarship, or How We (Narrowly) Defined American Humor

This essay begins with a story about the American frontier—one that most of you may already know—and I’d like to use it to try to explain why it is that we remember a few particular 19th Century humorists and NOT the 30 or 40 others who were also writing and publishing popular work during the pre-Civil War years and later.

Post-Revolutionary War America was a place of constantly shifting frontiers both to the west and to the south. In a given year, the western frontier might be Upstate New York and gradually moving westward, with the southern frontier in Virginia gradually moving further and further south; in later years, it became anything west of the Mississippi River as the influx of population pushed the borders westward and southward. In order to understand the humor that comes out of these liminal (border) spaces, one needs to think just a bit about what the frontier(s) were, how things operated there, and who migrated to those spaces. As the “new” settlements became more populated and the opportunities for jobs and wealth became less plentiful, pioneers moved further south and west in search of prosperity. Typically, we think of these folks as the rugged individualists who brought their skills and strength to bear on carving civilization out of the wilderness. In many cases, this was true.

However, in addition to the skilled laborers and farmers, the frontiers also attracted a seedier element–the con man and the pettifogger, the liar and the cheat, the gambler and the speculator–into these newly settled territories. Often they were one step ahead of criminal charges, lynching, or tar-and-feathering, and searching for a fresh start somewhere where they were an unknown quantity, and where new victims for their fraud were readily available. Given the nature of boom-towns on the frontier, it stands to reason that these would serve as topics for humor writers who inhabited that space.

These borderlands—primarily Georgia, Louisiana, and Alabama for the purposes of this study—are the regions from which those authors we call the Southwestern humorists sprang and flourished. When we speak of these humorists today, three or four of them remain and stand in for the whole of southwestern humor from 1830-1865 or so. Thomas Bangs Thorpe, for example, is still often anthologized and read in high schools and colleges occasionally. His “Big Bear of Arkansas” survives as a representative of the rough and ready braggart type of the American frontier. His language is a bit crude, his story quite exaggerated, and its conclusion a bit off-color. George Washington Harris’s Sut Lovingood tales are also occasionally anthologized. Students still respond to Sut with a mixture of horror and fascination, and most of the tales—“Parson John Bullen’s Lizards” comes to mind—demonstrate written slapstick humor at its best; and Sut’s character, while not exactly a con man, walks a fine line between “good fun” and that which is legal and/or moral. Similarly, Johnson J. Hooper’s Simon Suggs remains a memorable and sometimes anthologized character in American humor. If Sut often straddles the line between propriety and crudity, Simon Suggs broad-jumps that line, happily defrauding the country folk and slaves at every opportunity. His tag line is: “It is good to be shifty in a new country.” What these most often remembered and read authors have in common is the use of vernacular language, themes that involve fighting, fraudulent horse swaps, practical jokes that range from the mean spirited to the downright dangerous, and a frame featuring a narrator more refined and educated than the characters of their stories.

Happy Birthday, Samuel Langhorne Clemens. Not you, Mark Twain.

Tracy Wuster

November 30, 2015 will be celebrated as the 180th birthday of one Mark Twain—novelist, humorist, and all around American celebrity. I, for one, will not be celebrating.

You see, I recently finished up a book about Mark Twain, and I know, for a

fact, that Mark Twain was born on February 3,  1863. Or thereabouts. No one knows for certain, but that is as certain as we can be, so that is enough. And not so much born, but created, or launched…inaugurated…catapulted…

1863. Or thereabouts. No one knows for certain, but that is as certain as we can be, so that is enough. And not so much born, but created, or launched…inaugurated…catapulted…

That means that this February 3, 1863 will be Mark Twain’s 153rd birthday, which is not that fancy of a number, but it is getting up there for someone still so famous as to have people writing books about him—and more importantly, people reading books by him.

Sure, everyone knows that “Mark Twain” was really the pseudonym of Samuel Langhorne Clemens. Even early in his career, almost everyone knew that, often using the names interchangeably, as most Americans still do. Not as many people know the names Samuel Clemens used an abandoned before creating Mark Twain: “Grumbler,” “Rambler,” “Saverton,” “W. Epaminondas Adrastus Blab,” “Sergeant Fathom,” “Quintus Curtis Snodgrass,” “Thomas Jefferson Snodgrass,” and “Josh.” Selecting “Mark Twain” was clearly a wise choice, although the name would have had a second, nautical meaning for many nineteenth century folk.

Samuel Clemens mixed up the use of his given name and his chosen name—making the whole distinction a mush of confusion that is either a bonanza of psychological material or, alternately, meaningless. For most people, I would guess the distinction is meaningless trivia, which is fine. I’m just happy people still know and read books by Mark Twain. But, I for one, will still grumble when people wish Mark Twain a “Happy Birthday” each November 30th, and I will still try to correct them by pointing out that the “Mark Twain” they refer to really was born—or created—on February 3rd, 1863.

But what does it matter?