Ethical Conundrums: Gerhard Reinke’s Wanderlust and Las Hurdes

You probably never saw it, but it was a funny show with something and nothing to say. Back in 2003, Jimmy Kimmel’s Jackhole Productions produced six episodes of a show for Comedy Central called Gerhard Reinke’s Wanderlust. Each week, its fictional German host (played by American Adam Gardner) toured some part of the world – usually some part of the third world. Gerhard Reinke was a hapless traveler. He succumbed to some sort of travel-related malady in nearly every show – from bugbites to embarrassing erections.

When a situation demanded caution, he was gullible. Where compassion would have been appropriate, he was shrewd. After cheerily explaining that, “Bolivia’s economic crisis makes it one of the cheapest places in the world!,” he rather cruelly haggles over seemingly low-value currency with a presumably poor woman selling a llama fetus in La Paz’s “witch’s market.”

Though his travel skills were severely lacking, Reinke fared little better as a television host. On the easier side of the show’s humor, his thick German accent led to some cheap laughs when he visited “Wenice Beach” California. But his challenged hosting skills could demonstrate a sharper satirical edge as well. As evidenced in his celebration of Bolivia’s troubled economy, his narration rarely matched the tone demanded of a situation. While Gerhard cheerily described the miseries caused by international economic inequality, he was deadly serious when dealing with insubstantial maladies or undertaking any of his projects (like searching for Bigfoot or writing erotic fiction). Fundamentally, these moments of tonal contradiction evidenced a self-centeredness that appears to trouble the ethical positions of both the tourist and media consumer in a global economy. At the same time, it is a comedy and as such it is better at critiquing than offering solutions.

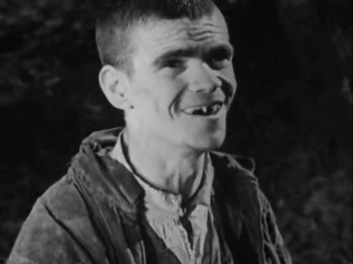

In this way, it is reminiscent of Luis Buñuel’s 1933 film Las Hurdes: Tierra Sin Pan (English: Land Without Bread). This film, also a mockumentary travelogue, offers its audience a view of an economically disadvantaged peasants living in the Hurdes region of Spain. While not as obviously comic as Wanderlust, Buñuel’s humor relies on a similar tonal mismatch. The narrator of this film remains disinterested and at times even amused as he describes and comments on the terrible conditions of the film’s subjects. Gerhard’s relationship to his audience is a bit more complicated. Unlike the disembodied “voice-of-God” narrator of Las Hurdes, Gerhard is a transparently flawed host. Laughing at Buñuel’s narrator feels somewhat like laughing at myself. The laughter directed at Reinke is less reflexive – it is directed at the over-confident “German” doofus. Still, laughing at Gerhard is not entirely unproductive. Although he does not implicate the viewer as directly as does Las Hurdes‘ narrator, we still must accept Reinke’s position as viewer surrogate in our relationship to this media text. And unlike in Buñuel’s film, we here see the figure of the tourist in some of its worst excesses. This kind of misery-tourism might be subtly suggested in Las Hurdes, but it is a major and explicit theme in Gerhard Reinke’s Wanderlust.

In perhaps its most obviously comic moment, Las Hurdes shows a goat scaling a rocky cliff. “One eats goat meat only when one of the animals is killed accidentally,” explains the narrator. “This happens sometimes when the hills are steep and there are loose stones on the footpath.” A puff of smoke billows in from offscreen and the goat falls. The narrator has lied to us. The goat did not trip – it was shot. While the whole film seems to ask what the viewer’s responsibility might be towards disadvantaged Others, this moment suspends those questions to ask more fundamentally what and how we actually know about the people and things we witness from the other side of the screen.

Similarly, though with more broadly comic strokes, Wanderlust mixes a heaping dose of falsity into its documentary explorations. Every episode devolves into some kind of fictional narrative as Gerhard joins a Marxist revolutionary group or struggles with an affliction known as “pee shyness.” So although a good part of both texts ask us to think about our relationship to other human beings, these moments undercut their moral imperative by asking how we can even know the experiences of others in these distant places. There seems to be on the one hand an imperative to act based on the documentary evidence of human suffering. But there is also a more radical proposition that we can’t trust texts like the ones we are watching, which undercuts the moral certainty of the first proposition.

So which is the more powerful argument? Neither Las Hurdes‘s narrator nor Gerhard Reinke (or Luis Buñuel or Josh Gardner) will tell us. Despite the apparent intended message of Las Hurdes, it offers a message of resignation in the face of suffering. While the concern with other humans seems the more ethically defensible position, the proposition that these media themselves are untrustworthy denies such neat moralism. Disturbingly, the warnings against being overly trusting of such appeals seems to be the more powerful message here. So don’t worry too much about the Hurdes or the poor woman selling the llama fetus: they might as well be fictional.