Marc Maron Mania

It is time to jump on the Marc Maron bandwagon. Really. Do it right away because, well, things could go bad at any moment. I know this because I have been following Maron for almost six months now. Six months of unadulterated laughter at a guy who builds his material on the core fact of his life: things could go bad at any moment. Maron is having a good year in the public realm. He is making money and getting praise from critics and new fans alike. And it is all deserved. He is provocative (which means he is funny but pisses people off) and likable (which means that he is funny but people feel sorry for him). Maron has already earned some attention on HA!. For two excellent pieces, see: Matthew Daube on Marc Maron; ABE on Marc Maron.

He is cooking on all burners, putting out wonderful material in the last couple of years: Thinky Pain, an album and concert video on Netflix) and This Has to Be Funny being released in August 2014, Attempting Normal, a book with solid praise thus far, and Maron, the wonderful television show in its second season on IFC and available on Netflix.

Maron on his youth baseball experience from Thinky Pain

Here is a brief scene from the sitcom Maron as he interviews C.M. Punk: Interview with C.M. Punk on Maron

He is an overnight twenty-five-years-in-the-making success. And the time to jump in an enjoy this dynamo is now because, well, who knows what is around the corner? He’s just a guy trying to be an adult, OK? Sometimes it goes well. Sometimes, not so well. Maron has found a way to make his pain pay. (He just got $ 4.99 from me for a premium membership of WTF). The podcast started in 2009 and still runs out of his garage. In spite of this humble setting (or related to it, perhaps), Maron draws in some of the biggest stars of comedy and Hollywood, as well as in the music industry. Here are a few of his guests just from the last few months: Josh Groban, Billy Gibbons, Vince Vaughan, Ivan Reitman, Lena Dunham, Laurie Kilmartin, and Will Ferrel, and so on. WTF is an ideal text for studying the state of American humor. I would consider it a valuable (perhaps essential) forum for anyone interested in studying/learning the craft of American stand up comedy and its interdependence on all facets of American pop culture, especially music.

Over the last several years, Maron via WTF has steadily put together a remarkable collection of interviews of some of the best comic minds of our time, along with a wide array of other artists of varying interests. If you have yet to listen to WTF, well, wtf?

Just this past week, WTF hit its 500 podcast. Here is a link to a list of the episodes and the guests: WTF Episode Guide. The most recent 50 are available free via the the app or online here: WTF Podcast Home

Rolling Stone (Rolling Stone Article) listed Maron as on The 10 Funniest People, Videos and Things of the Coming Year in 2011. In this brief article, Jonah Weiner calls Maron an “acid-tongued rage-prone satirist.” That is just the thing. Maron causes critics to use hyphenated terms to describe him. He is THAT good. Actually, Weiner makes the right call as he talks about WTF as his most important work to date. He calls it a “series of unvarnished shit-shoots with comedians that move from laugh-geek joke autonomy to quasi-therapeutic venting.” Geez, three more hyphenated terms in one sentence. Do you see what Maron can do? I did not know how important hyphens were to Rolling Stone, but I digress. Underneath the god-awful (hyphen!) phrasing of the description is a crucial point.

WTF balances formidable discussions of the craft of humor (what Weimer calls “joke anatomy”–what? no hyphen?) and psychoanalysis, all of which teeters on disaster at any given moment, and all of it thoughtful. Marc Maron is a funny comic writer; he is solid performer in his sitcom; and he is compelling on stage, but he is a master of the interview. He does not know why. In the 500 episode he acknowledges the praise for his interviewing skill but seems baffled by how it came about. It reminds me of the anecdote about Bob Newhart, a master of stammering timing. Newhart, when asked how he managed to so perfectly create the illusion of talking on the phone, for instance, responded that he simply waited the amount of time it would take for someone on the other end of the fictional conversation to say something. Brilliant. Newhart deflects any praise for his skill and pretends that his timing is innate and open to anyone. Nah. Newhart has it; Maron has it, too. It has something to do with talent, but it is also a work in progress. In either case, Maron comes across as genuinely curious about how his guests struggle with craft (whether it is comedy, music, acting, writing, whatever) AND their inner demons. And he gives them the space to explore the humor and challenges of both. He also makes them talk about his own issues. Maron has issues.

In the New York Times (Jan. 2011; NYTimes Article on Maron), calls him “angry probing, neurotic and a vulnerable recovering addict.” Well, American comedy, right? He has been called a mix of Woody Allen and Lenny Bruce, which is both accurate and too easy. As he states in his introduction provided on the WTF website, he prefers the combination one of his fans provided: an Iggy Pop Woody Allen. Yes, American comedy of anxiety with a punk ethos. To give you a taste of this Maron mix, note the following three quotes included in the banner for the “about” section of the WTF website:

–“TV is great because no one knows when to retire and you can watch the full arc of success, sadness and decay.”

–“I’m glad to be part of the war on sadness. I’m a part time employee of the illusion that keeps people stupid.”

–“In most cases the only difference between depression and disappointment is your level of commitment.”

It’s time to jump on the Marc Maron bandwagon with a deep level of commitment. I just paid five bucks for premium access for the next six months. And I am looking into a 20 dollar mug.

The Trouble Begins at Nine?: Mark Twain, “A Speech on Women,” and Blackface Minstrelsy

“Trouble,” as I may have said once or twice, was Twain’s trademark.

On 11 January 1868, Mark Twain was asked to give a speech (printed in full below) responding to a toast at the Washington Correspondents’ Club. The toast: “Woman, the pride of the professions and the jewel of ours.”

John F. Scott, ed. New York: Dick & Fitzgerald, 1868. Collection of the author.

The speech was well received and widely re-published in newspapers — and also in an 1868 book called Brudder Bones Book of Stump Speeches, and Burlesque Orations, which contains a variety of humorous speeches and sketches from the blackface stage, variety houses and the lecture circuit, all indiscriminately mixed together. Twain, though, is given special recognition in the text, being referred to as “the celebrated humorist.”

While Twain was initially tickled both by his speech and its coverage in the press — and even sent a copy to his own mother, who apparently loved it — he later worried about whether the speech was too vulgar in places. In the various reprints, it would seem that some editors agreed with him, as they omitted bits here and there. Their choices are interesting.

The Washington Star version (13 January 1868), for example, mildly says that Twain “responded” to the toast. It omits an off-color reference to wives cuckolding their husbands and bearing others’ children and an appreciative tribute to Eve in the pre-fig-leaf days.

Brudder Bones, on the other hand, offers that Twain “was called upon to respond to a toast complimentary to women, and he performed his duty in the following manner.” The book changes that “manner” a bit, by striking the final, conciliatory paragraph that puts all “jesting aside” with a toast honoring each man’s mother. Brudder Bones also omits Twain’s stated desire to “protect” women, apparently not seeing this as necessary or appropriate, or perhaps funny. Like the Star, the minstrel show version omits the reference to women’s infidelity and the children that arise from it, but reprints in full the appreciation of Eve, which celebrates female beauty and sexuality.

But for Twain enthusiasts and scholars, Brudder Bones also includes another item of interest. It is well known that Twain advertised his lectures with various versions of the phrase “The Trouble Begins at Eight.” And his favorite blackface minstrel troupe, the San Francisco Minstrels, also used variations of the same phrase to advertise their shows for almost two decades, an association Twain seemed to enjoy — and certainly never complained about. Brudder Bones, though, confirms that both Twain and the San Francisco Minstrels likely had an earlier source for that particular phrasing. The 1868 book includes a sketch written and performed by blackface minstrel, entrepreneur, and promoter Charley White — De Trouble Begins at Nine, as played at the American Theatre, 444 Broadway. This theatre burned to the ground on 15 February 1866, according to theatre historian George Odell (VIII.84).

But for Twain enthusiasts and scholars, Brudder Bones also includes another item of interest. It is well known that Twain advertised his lectures with various versions of the phrase “The Trouble Begins at Eight.” And his favorite blackface minstrel troupe, the San Francisco Minstrels, also used variations of the same phrase to advertise their shows for almost two decades, an association Twain seemed to enjoy — and certainly never complained about. Brudder Bones, though, confirms that both Twain and the San Francisco Minstrels likely had an earlier source for that particular phrasing. The 1868 book includes a sketch written and performed by blackface minstrel, entrepreneur, and promoter Charley White — De Trouble Begins at Nine, as played at the American Theatre, 444 Broadway. This theatre burned to the ground on 15 February 1866, according to theatre historian George Odell (VIII.84).

So . . . the trouble actually began at nine — nine to ten months before Twain’s inspired first use of a variation of the phrase.

And now, let’s take a look at the mild trouble Twain stirred up about women at the Correspondents’ Club, trouble that he felt that “they had no business” reporting “so verbatimly.” For those who appreciate Twain’s later 1601, this “trouble” will seem tame indeed, but it does have its charms:

**********************************************************

A Speech on Women by Mark Twain

Washington Correspondents’ Club, 11 February 1868

MR. PRESIDENT: I do not know why I should have been singled out to receive the greatest distinction of the evening — for so the office of replying to the toast to woman has been regarded in every age. [Applause.] I do not know why I have received this distinction, unless it be that I am a trifle less homely than the other members of the club. But, be this as it may, Mr. President, I am proud of the position, and you could not have chosen any one who would have accepted it more gladly, or labored with a heartier good-will to do the subject justice, than I. Because, sir, I love the sex. [Laughter.] I love all the women, sir, irrespective of age or color. [Laughter.]

Human intelligence cannot estimate what we owe to woman, sir. She sews on our buttons [laughter], she mends our clothes [laughter], she ropes us in at the church fairs — she confides in us; she tells us whatever she can find out about the little private affairs of the neighbors ; she gives us good advice — and plenty of it — she gives us a piece of her mind, sometimes — and sometimes all of it ; she soothes our aching brows; she bears our children — ours as a general thing. In all the relations of life, sir, it is but just, and a graceful tribute to woman to say of her that she is a perfect brick.1 [Great laughter.]

Wheresoever you place woman, sir — in whatever position or estate — she is an ornament to that place she occupies, and a treasure to the world. [Here Mr. Twain paused, looked inquiringly at his hearers and remarked that the applause should come in at this point. It came in. Mr. Twain resumed his eulogy.] Look at the noble names of history! Look at Cleopatra! — look at Desdemona! — look at Florence Nightingale! –look at Joan of Arc! –look at Lucretia Borgia! [Disapprobation expressed. “Well,” said Mr. Twain, scratching his head doubtfully, “suppose we let Lucretia slide.”] Continue reading →

Ask a Slave: The Exasperating World of Teaching Tourists about American Slavery

Tourists say the dumbest things. They travel the globe ostensibly to learn and to gain experiences so that when they return home they can do so as more well-rounded and informed human beings. Well, that’s the dream anyway. Tourists are always out of place, they are often pretending to be (much) smarter than they are, and they carry with them a sense of entitlement–all of these factors set them up to be perennially funny as objects of ridicule. Few things are funnier than ignorance, but when it combines with arrogance, then a wonderfully silly comic star is born: the American tourist, a figure of derision for about hundred and fifty years now.

It was Mark Twain who first popularized and perfected the American tourist, in his best-selling The Innocents Abroad in 1869, a narrative of a bumbling five-month tour–America’s first pleasure cruise–across the Atlantic and around the Mediterranean Sea to see the “Old World.” He later built on that persona in other travel books like A Tramp Abroad (1880) and Following the Equator (1897). Twain captured the perils of tourism in many ways, but one of his most effective and hilarious shticks was to mock the inherent ignorance and arrogance of tourists simply by reporting what they said.

Tourists say the dumbest things. Just ask Azie Dungey, an actor who, while looking for stage work in the Washington D.C. area, found roles, as she puts it, playing “every black woman of note that ever lived. From Harriet Tubman to Diane Nash to Claudette Colvin to Carline Branham–Martha Washington’s enslaved Lady’s maid.” Readers here may be too timid to ask this: Is that THE Martha Washington, President George Washington’s wife? Yup. History is fun. Ms. Dungey, during the energy and optimism infused into the presidential election of 2008 and throughout President Obama’s first term, Azie Dungey supported herself by playing a slave who served the first, first family. American irony at its best.

Her role is as “Lizzie May,” a fictional character drawn from Ms. Dungey’s experiences performing as a slave woman at George and Martha Washington’s home named Mount Vernon, now a popular tourist site. And her forum is Ask a Slave: The Web Series. The short sketches recreate many of the questions that tourists posed to Ms. Dungey over the years. Ask a Slave is promoted as “Real Questions, Real Comedy.” It will make you cringe.

When tourists reveal their ignorance and arrogance, we have what is called in the profession “a teachable moment.” A traditional method of trying to encourage a learning process is called the Socratic Method, named after Socrates that famous smart guy from ancient Greece. He is dead now. The method involves getting people to ask questions and from the answers to encourage more questions and thereby lead to the gathering of knowledge–and, from that process, achieve the gaining of wisdom. Or something like that. Tourists all over the United States (and the world, for that matter) are often encouraged to ask questions of their guides. At many historical sites, guides are often complemented by historical re-enactors to create “living history.” It is an appealing bit of stage craft. “All of history is but a stage, and we are merely reenactors and tourists.” Shakespeare wrote something along those lines. I just updated it.

But when the questions are so clueless, what’s a slave to do?

Well, the actor Azie Dungey performed her role to the best of her ability (and with much patience), but all the while she collected information, and now, as Lizzie May, she has some different answers to give. She, with the help of other members of the crew, are re-enacting those tourist re-enactments and providing the rest of us with our own funny teachable moments. The first episode immediately reveals why the online comedy series has caught fire.

Lizzie May is a significant expansion of the role that Ms. Dungey played at Mount Vernon. She is able to provide answers that would have gotten her fired at Mount Vernon, all the while maintaining a demeanor that is seemingly polite and deferential and that the original role demanded. Yet the answers are assertive and thus subversive. She thereby provides a compelling satirical voice. The resulting humor is well worth viewers’ time and offers us our own teachable moments.

Ignorance is funny. It has always been funny because it provides us the wonderful opportunity to laugh at someone else’s stupidity. Fortunately, there is an endless supply of it, so humorists can always find some facet of human behavior to exploit for laughs. When the subject matter is tied to the legacies of slavery, the humor has an unavoidable edge. One thing that the tourist questions reveal beyond their stupidity is a desperation for self-affirmation, or an almost pathological need to lessen the horror of slavery, to give many modern tourists more distance from the slaveowners and supremacists in their racial family tree. The need is understandable; the ongoing moral cowardice, however, is tiresome to say the least.

Happy Birthday, Thom Gunn!

Thom Gunn wasn’t an overtly humorous poet, but his sharp wit, incisive irony and visceral imagery were brilliant. His poetry has been described as capturing “the experience, not the idea.”

His is a voice of isolation and existentialism with overtones of nihilism––so vividly evoked that we’re apt to see glimpses of ourselves at odd moments. Perhaps, therein lies the humor.

Gunn’s subject matter isn’t for sissies. It includes his mother’s suicide, drug use, gay erotica and the AIDs deaths of his friends. (Lest you get the wrong impression, his personality has been described as upbeat –– not morose.)

Below are two of his tamer masterpieces: “Considering the Snail” as performed by Gary of SpongeBob fame, and a text version of “The Unsettled Motorcyclist’s Vision of His Death.”

The Unsettled Motorcyclist’s Vision of His Death

Across the open countryside,

Into the walls of rain I ride.

It beats my cheek, drenches my knees,

But I am being what I please.The firm heath stops, and marsh begins.

Now we’re at war: whichever wins

My Human will cannot submit

To nature, though brought out of it.

The wheels sink deep; the clear sound blurs:

Still, bent on the handle-bars,

I urge my chosen instrument

Against the mere embodiment.

The front wheel wedges fast between

Two shrubs of glazed insensate green

– Gigantic order in the rim

Of each flat leaf. Black eddies brim

Around my heel which, pressing deep,

Accelerates the waiting sleep.I used to live in sound, and lacked

Knowledge of still or creeping fact.

But now the stagnant strips my breath,

Leant on my cheek in weight of death.

Though so oppressed I find I may

Through substance move. I pick my way,

Where death and life in one combine,

Through the dark earth that is not mine,

Crowded with fragments, blunt, unformed;

While past my ear where noises swarmedThe marsh plant’s white extremities,

Slow without patience, spread at ease

Invulnerable and soft, extend

With a quiet grasping toward their end.

And though the tubers, once I rot,

Reflesh my bones with pallid knot,

Till swelling out my clothes they feign

This dummy is a man again,

It is as servants they insist,

Without volition that they twist;

And habit does not leave them tired,

By men laboriously acquired.

Cell after cell the plants convert

My special richness in the dirt:

All that they get, they get by chanceAnd multiply in ignorance.

—- Thom Gunn

Teaching American Satire: A New Piece for the Classroom from the Onion

It is fun to teach humor. Laughter keeps students awake more effectively than most things. The promise of relief or diversion from the cultural and personal stresses implicit in all humor (and explicit in much of it), to my mind, not only makes for more pleasant classroom discussions but also helps to make those discussions more productive. This I believe.

But I have my doubts when it comes to exploring satire. I have revealed my misgivings in this spot before (Teaching the Irony of Satire (Ironically); see also Sharon McCoy’s excellent response: Embracing the Ambiguity of Satire).

Within the overall umbrella of my courses on American Humor, satire demands its space, and rightfully so. But it’s harder to get through the material, and methinks many students pick up on my hesitations here and there. I don’t mind the difficulty factor, it’s the pain of the subject matter that wears me out. The suffering underlying much of humor in general stands foregrounded in satire. This is the nature of the art form. Satire cannot hide its rage, or its hopelessness, and as a result there is very little room for the pleasant relief of laughter. Satire is rarely funny “ha ha,” or funny “weird.” It’s just painful.

I have just read what I consider to be one of the most engaging pieces of satire on political and cultural intransigence that I have encountered since first reading Mark Twain’s “The War Prayer,” a work by the American master that is perfect both in its conciseness and its artistic vision.

Twain’s short piece, which has a stranger translate the prayers of a people on the verge of war, is powerful for its accuracy as a comment on the human capacity for making war in the name of god and its recognition that the commentary is timeless because the war making machine is timeless, and unending. Students will always study it because they will always understand its targets. The Onion has just provided another piece that seems, to me, worthy of being taught alongside Twain’s work.

It is an “Editorial Opinion” that first appeared on August 13, 2013 (Issues 49.33). The title is: “The Onion” Encourages Israel and Palestine Not to Give a Single, Goddamn Inch.”

Here is a link to the article: http://www.theonion.com/articles/the-onion-encourages-israel-and-palestine-not-to-g,33473/

Standing in opposition to “the international community” which has pleaded with the two sides to meet to discuss peace, The Onion satirically asks the sides to remain steadfast and persist in absolutist positions:

“Israelis and Palestinians, you must accept nothing short of total victory against those who threaten your religion and way of life. Sacrificing just one of your ideals would at this point be tantamount to compete and utter failure.”

The writers of The Onion then follow this assertion with details that simply recount the history of the last 60 years (and by implication 2,000 years?) in four concise sentences:

“If a settlement is built, you must attack it. If a settlement is attacked, you must rebuild it. Rocks must be met with bullets; bullets must be met with rocket fire; rocket fire must be met with helicopter assaults. This is the only noble way forward for either side.”

Noble. Forward. The writers know, and readers know, the words “noble” and “forward” serve as the key bits of irony here. There is nothing noble in the bloodshed, nothing forward looking about continued intransigence.

Building on this sardonic tone, the satire gets heavier and heavier, and the reader wants relief while at the same time knowing that none is forthcoming. As with Twain’s work, the writers are devoted to the point of the satire, which is the grotesque pointlessness of continued aggression. The secondary target of the piece, though, may also be the ever-present demands from the international community to urge the parties to sue for peace. Pointless. I don’t really believe that peace efforts are pointless, by the way, but it seems the accurate thing to say here in the context of The Onion satire, the art. If we are to teach such aggressive and unnerving satire, we must be ready to accept the full brunt of the hopelessness the piece addresses. And thus figure out a way to help students talk about it. I am open to suggestions.

I just know that as I read this, I wanted an outlet, some peek from behind the curtain from the jester. But it is not there because there is no peace ready to peek out from behind any curtains either. The article ends concisely and with a key repetition:

“Remain steadfast. Remain strong. And never give up your noble fight, even if it takes several more generations.”

That, my gentle readers, is first-rate satire. It is exhausting and no fun at all.

Truthiness and American Humor

Stephen Colbert, in the inaugural episode of the Colbert Report (October 17, 2005), coined the word truthiness to capture the underlying absurdity of the human preference to assert a truth that arises from a devout belief in one’s gut rather than one supported by facts (see:Colbert Introduces Truthiness). Truthiness reflects the desire of a formidable section of the population (or is it the entire population?) to assert that what they believe to be true is true, not necessarily because the facts support it but because they want to believe it so strongly. Colbert, in character, asserted that the nation was at war between “those who think with their heads and those who know with their hearts.” As Colbert put it in an interview with the A.V. Club by The Onion (January 26, 2006), “facts matter not at all. Perception is everything” (see: Colbert Interview).

To say that the word took off is a lame understatement. A Google search of “truthiness” yields 969,000 hits. Wikipedia–where I get all of my facts with full enjoyment of the ironic potential of that statement–has an article on the word that offers 57 footnotes pointing to a wide range of popular culture and media sources. If you are so inclined, you could follow #truthiness on Twitter and receive a constant string of observations from some of the brightest minds of the time, but I can’t recommend that in good conscience.

In no uncertain terms, truthiness is in the American grain, politically and socially. Colbert claims that the word–and its satirical context–is the thesis for the Colbert Report itself. Whether all of his viewers really get that could be debated, at least if one considers viewers early in the run of the show. See the 2009 article examining the complicated range of audience responses to the Colbert Report by Heather LeMarre here: The Irony of Satire. I have commented on that conundrum in an earlier post questioning the power of satire — Teaching the Irony of Satire (Ironically). That essay was followed by a first-rate essay by Sharon McCoy reaffirming at least some of my optimism — (Embracing the Ambiguity and Irony of Satire). By 2013, however, Colbert has appeared out-of-character enough and has built such a clear following, it would be much more difficult to find an audience who would be as confused regarding his true political thinking as some viewers were in 2005. He is too big, and he has appeared more often out-of-character via interviews in a variety of outlets. He is liberal, OK?

I would argue that no humorist has ever called into service a word with more usefulness to cultural and media critics, and to lovers of irony. But the concept behind truthiness is not Colbert’s. It’s the cornerstone of American humor, and our greatest writers and characters have built a tradition of humor forever exploiting the grand American attraction to self-delusion, to the power of desire over the power of facts. It is what makes us so funny.

Washington Irving gave us our first enduring humorous character through the sleepy ne’er-do-well Rip Van Winkle, a man who abandons his family for twenty years and returns after his wife’s death to become a grand old man of the town, living the life he always wanted–talking and drinking with friends. Irving brings Rip to readers through his narrator, “Geoffrey Crayon” who takes the story from “Deidrich Knickerbocker,” who takes the story verbatim from Rip himself. That’s a lot of room for creative use of truthiness. Rip is no match for the idealized romantic heroic male of the revolutionary era, the Daniel Boone’s who built it, so to speak. He presents a different kind of American. He does not fight for love of country or for political freedom; he sits out the war. He does not build a homestead thus failing to accept his role in the making of the national Jeffersonian dream. Nope. Within the story are all the facts to show that Rip is a sorry excuse for a man and a lousy American, a troubling subversive. But we love him because he seems like such a nice guy, and his wife is such a pain–as Rip tells it. Of course, his narrative is self-serving–and successful. Although some townspeople clearly know he is a liar, most accept his story of sleeping for twenty years–because it feels right, or at least it allows them to go about their business. They are willing to believe in the mysteries of the hidden corners of the Catskills, but more importantly, they are eager to believe in a man they like. It just feels right. And easier.

Readers, moreover, do the same. They like him; they hate Dame Van Winkle. They forgive Rip his indiscretions and welcome him back into the fold. They believe him because he seems so earnest. Rip abides, bless his heart. They believe, for the similar reasons, in the exploits of Daniel Boone. But I digress. All of Rip’s late-life success in becoming a center of attention is made possible by his willingness to lie and the inherent desire of most of the townspeople to believe his story simply because they want to. Facts and deductive reasoning be damned. That is funny.

Washington Irving, in giving us Rip, deserves recognition as the first worthy exploiter of truthiness in American humor. The great master of the 19th century was, of course, Mark Twain–who I will come back to in another post. There are many others, from the eternal optimism of Charlie Chaplin, to the befuddled female misfits of Dorothy Parker, to the secret dreams of Walter Mitty envisioned by James Thurber, to the disturbed struggles of Lenny Bruce, to the white Russians of the Dude from the Coen brothers’ The Big Lebowski. It is a long list that has as its current master-artist Stephen Colbert. It is a timeline of writers, characters, comedians, and satirists covering just under two hundred years (using the 1819 publication of “Rip Van Winkle” as my starting point).

For some reason, there is still a need for satirical minds to tell subversive stories and to exploit the absurdities of American culture because there also remains a powerful urge for many Americans to shun facts and go with their gut to serve their own desires and belief systems. They find regular affirmation in popular culture and politics. One could be somewhat disappointed that after all this time there is still so much work to be done to defeat the powers of truthiness in our political systems and social structures. Not me. I believe things will get better. I can feel it in my gut.

Because Rip abides.

Meta-Racist Airplane Jokes: The Foolish Audience and Didactic Humor

What do you call a black man flying an airplane? A pilot, you racist.

It is not complicated, but this meta-joke activates a complex meaning-making process. The setup connotes a genre of racist jokes, inviting the listener to imagine what possible stereotype about black men will fulfill the question in an unexpected way. The answer of “a pilot” is surprising precisely because it is unsurprising. If orthodox racist jokes tend to fulfill psychoanalytic models in their ability to express otherwise forbidden acts of expression, this joke plays more on the surprise theory by inverting dramatic irony to pleasurably expose the listener’s own prejudices and ideally creating some positive self-awareness in the process.

Dramatic irony occurs when the audience knows something a fictional character does not. I read the above joke as an inversion of that particular form because the “audience” for this joke is the one kept in ignorance until the moment of the punchline. Though not necessarily given to social justice for every listener, this joke is ideally didactic in that it makes a pleasurable game of exposing the listener’s prejudices. Neither this form of humor nor its seeming aspirations to a small lesson in social justice are limited to verbal jokes though. To illustrate these points, I turn to an example that uses visual and verbal language to similar ends with relevant contemporary implications.

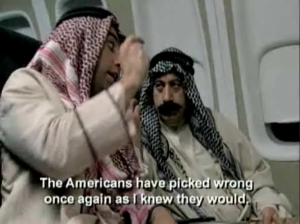

In 2003, Chappelle’s Show aired a sketch titled “Diversity in First Class.” Although given to left-leaning rhetoric, Chappelle’s Show was not above admissions of prejudice in certain situations. Taking place on a commercial airplane, the camera pans past a pair of men coded as Middle Easterners by their clothing and language. Engaged in a heated discussion, their performance displays aggression in both speech and hand motions. Clearly meant to invoke the image of Islamic terrorists, its original airdate less than 18 months after 9/11 framed its reading in terms of that national trauma. Subtitles further encourage reading the pair as a threat, adding verbal cues to the visual language connoting terrorism. But as the men continue, the subtitles reveal the true nature of their conversation.

By leading his expectations in one direction before dashing them, this contradiction between image and reality makes the viewer foolish. Not only that, but these Others discuss a well-known bit of Western pop culture, making their conversation familiar and laughably non-threatening.

In the Archives: Ambrose Bierce, “Wit and Humor” (1911)

Tracy Wuster, In the Archives

While Ambrose Bierce was considered, during his lifetime (and since), as an American humorists, he has been hard to fit into a general schema of American humor. Bierce doesn’t make it into Constance Rourke’s American Humor: A Study of National Character, maybe because he was opposed to the common man and the writer of dialect that figures so prominently in Rourke’s view of American humor. As Blair and Hill point out in America’s Humor, Bierce was a wit whose pen functioned as a scalpel often aimed at the common man and colloquial speech, presaging a movement toward wit and urbanity, toward alienation and fantasy, away from the native soil of 19th century humor. Interestingly, Bierce’s views on humor do not seem to have gotten much attention from humor studies scholars.

In The Devil’s Dictionary (1906), his attitude toward the humorist becomes clear:

HUMORIST, n. A plague that would have softened down the hoar austerity of Pharaoh’s heart and persuaded him to dismiss Israel with his best wishes, cat-quick.

Lo! the poor humorist, whose tortured mind

See jokes in crowds, though still to gloom inclined—

Whose simple appetite, untaught to stray,

His brains, renewed by night, consumes by day.

He thinks, admitted to an equal sty,

A graceful hog would bear his company.Alexander Poke

SATIRE, n. An obsolete kind of literary composition in which the vices and follies of the author’s enemies were expounded with imperfect tenderness. In this country satire never had more than a sickly and uncertain existence, for the soul of it is wit, wherein we are dolefully deficient, the humor that we mistake for it, like all humor, being tolerant and sympathetic. Moreover, although Americans are “endowed by their Creator” with abundant vice and folly, it is not generally known that these are reprehensible qualities, wherefore the satirist is popularly regarded as a soul-spirited knave, and his ever victim’s outcry for codefendants evokes a national assent.

Hail Satire! be thy praises ever sung

In the dead language of a mummy’s tongue,

For thou thyself art dead, and damned as well—

Thy spirit (usefully employed) in Hell.

Had it been such as consecrates the Bible

Thou hadst not perished by the law of libel.Barney Stims

WIT, n. The salt with which the American humorist spoils his intellectual cookery by leaving it out.

Bierce seems to have written sparsely about humor and wit directly in his voluminous writings. One piece, though, is of special note in the discussion of wit and humor. Published in The Collected Works of Ambrose Bierce, Vol. X: The Opinionator (1911), the essay “Wit and Humor” may have been a revision of “Concerning Wit and Humor” from the San Francisco Examiner (from either or both June 26, 1892 and March 23, 1903; 12).

His essay on “Wit and Humor,” obviously sides with the wit–not that there are any in America. Like many essays on humor in the nineteenth century (see Hazlitt or Lowell or Repplier, for examples) the distinction between wit and humor is central for Beirce, but unlike those others, Bierce is willing to more clearly distinguish between the two, and his essay is shorter and more readable than many. Interesting that the piece is not regularly, or so far as I can tell, ever reprinted in collections on humor. Enjoy

****

(98)

Wit and Humor

If without the faculty of observation one could acquire a thorough knowledge of literature, the art of literature, one would be astonished to learn “by report divine” how few professional writers can distinguish between one kind of writing and another. The difference between description and narration, that between a thought and a feeling, between poetry and verse, and so forth–all this is commonly imperfectly understood, even by most of those who work fairly well by intuition.

The ignorance of this sort that is most general is that of the distinction between wit and humor, albeit a thousand times expounded by impartial observers having neither. Now, it will be found that, as a rule, a shoemaker knows calfskin from sole-leather and a blacksmith can tell you wherein forging a clevis differs from shoeing a horse. He will tell you that it is his business to know such things, so he knows them. Equally and manifestly (99) it is a writer’s business to know the difference between one kind of writing and another kind, but to writers generally that advantage seems to be denied: they deny it to themselves.

I was once asked by a rather famous author why we laugh at wit. I replied: “We don’t–at least those of us who understand it do not.” Wit may make us smile, or make us wince, but laughter–that is the cheaper price that we pay for an inferior entertainment, namely, humor. There are persons who will laugh at anything at which they think they are expected to laugh. Having been taught that anything funny is witty, these benighted persons naturally think that anything witty is funny.