Gertrude Stein’s Serious Play

Photographs of Gertrude Stein are typically humorless.

Take this almost stern-looking image of her at work or this one with her Baltimore friends, Etta and Claribel Cone, who later visited Stein in Paris and were inspired, through her, to bring the remarkably large and impressive Cone Collection at the Baltimore Museum of Art of Cubist and Impressionist art to Baltimore.

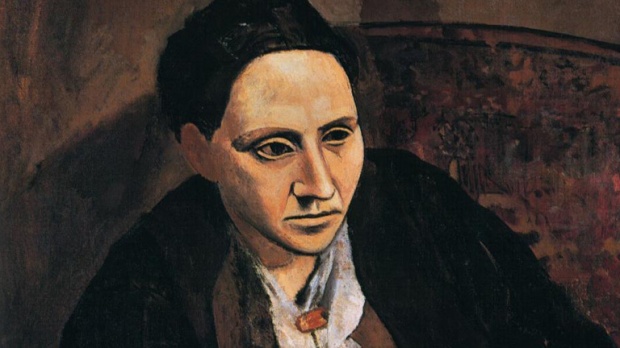

Or this famous Picasso portrait of the author, which seems to capture the pensiveness and glumness of her era.

Even Kathy Bates’s portrayal of Stein in Woody Allen’s well-timed comedy Midnight in Paris is one of the least funny impersonations in the film.

Yet her poetry is nowhere near this sober.

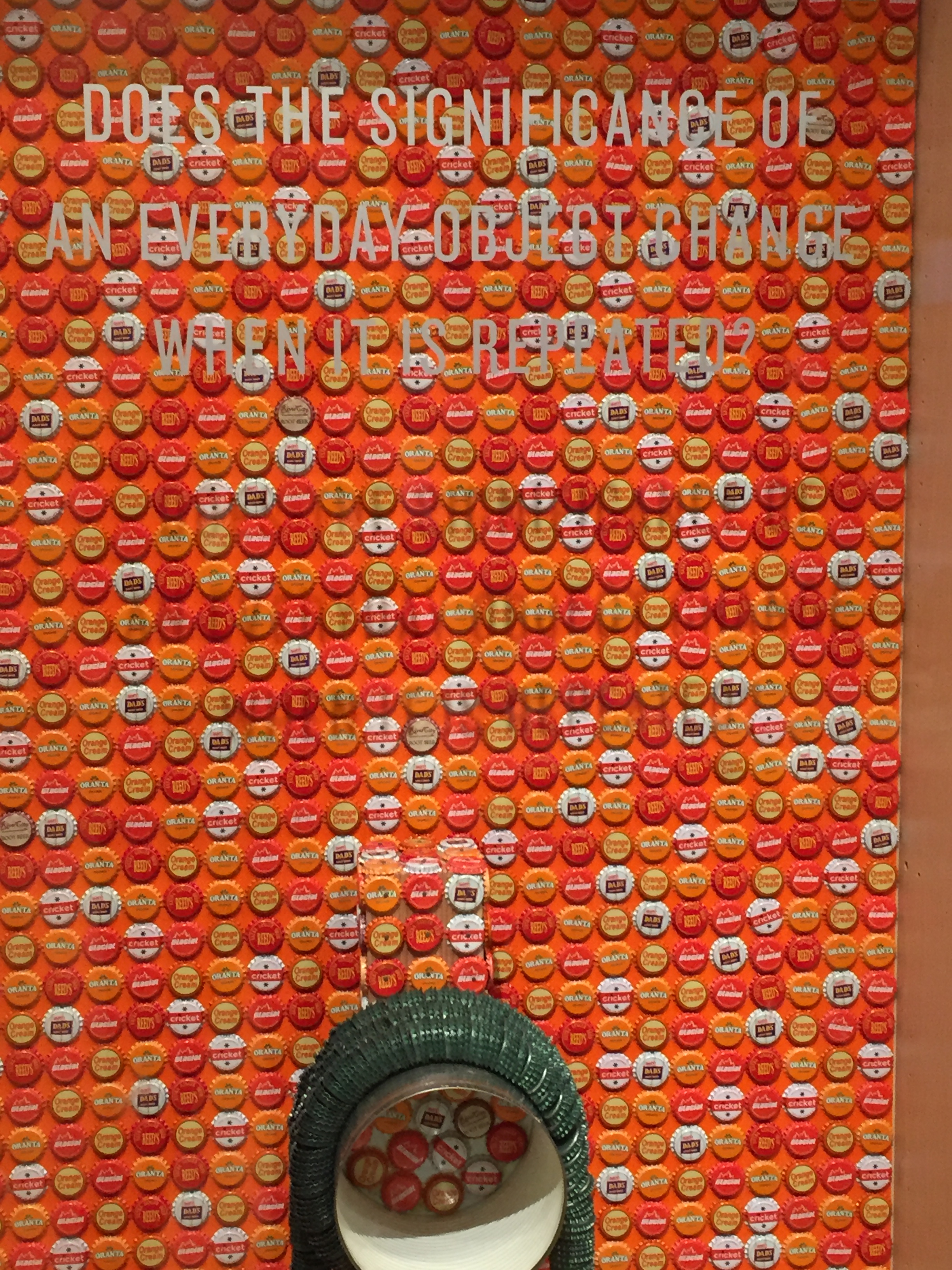

Below is a short appreciation of a few of her poems. Like conceptual art, they create meaning through grammatical disorientation, repetition, and odd angles. And like conceptual art, their strangeness can really make a reader mad unless that reader is prepared, as very few museum-goers are, to find this all amusing and then begin to dissect the puzzle.

Image from the Baltimore Museum of Art:

And as you read you may also wonder (my students often do) whether this writing is nothing more than pretentious word vomit––a clever if silly mind game––or does it contain pleasant, even human levity–even a touch of soul.

And as you read you may also wonder (my students often do) whether this writing is nothing more than pretentious word vomit––a clever if silly mind game––or does it contain pleasant, even human levity–even a touch of soul.

Does the humor, if it’s there, come from our own ability to laugh at ourselves, having discovered through her poetry that we are too precious about and at the same time not careful enough about language? Should we feel serious about overturned grammar, or should we feel playful about it, or both? Should we laugh at repetition or feel that it’s meaningful, or both?

Image from the Baltimore Museum of Art:

Nearly seventy years after her death, this kind of poetry is rich with the heaviness of her time: world wars; gender prejudice, even from those she mentored and guided; anti-semitism–even perhaps her own self-directed variety; stark inequalities between classes; and perhaps understandably bleak, bleak views of life among artists. Although her words carry this heritage and the mark of her time, she breaks open language and almost seems to free it from its literal certitudes. In this respect she is like Emily Dickinson; both were masters of language, yet in their baffling play, they almost seem to prefer giddiness and silence.

Nearly seventy years after her death, this kind of poetry is rich with the heaviness of her time: world wars; gender prejudice, even from those she mentored and guided; anti-semitism–even perhaps her own self-directed variety; stark inequalities between classes; and perhaps understandably bleak, bleak views of life among artists. Although her words carry this heritage and the mark of her time, she breaks open language and almost seems to free it from its literal certitudes. In this respect she is like Emily Dickinson; both were masters of language, yet in their baffling play, they almost seem to prefer giddiness and silence.

Image of Gertrude Stein’s deceptively dreary home while studying as a medical student in Baltimore:

Susie Asado

Gertrude Stein, “Susie Asado” from Selected Writings of Gertrude Stein. (New York: Peter Smith Publishing, 1992). Copyright © 1992 by Calman A. Levin, Executor of the Estate of Gertrude Stein. Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Gertrude Stein.

Source: The Norton Anthology of Modern and Contemporary Poetry Third Edition (W. W. Norton and Company Inc., 2003)

A Substance in a Cushion

The change of color is likely and a difference a very little difference is prepared. Sugar is not a vegetable.

Callous is something that hardening leaves behind what will be soft if there is a genuine interest in there being present as many girls as men. Does this change. It shows that dirt is clean when there is a volume.

A cushion has that cover. Supposing you do not like to change, supposing it is very clean that there is no change in appearance, supposing that there is regularity and a costume is that any the worse than an oyster and an exchange. Come to season that is there any extreme use in feather and cotton. Is there not much more joy in a table and more chairs and very likely roundness and a place to put them.

A circle of fine card board and a chance to see a tassel.

What is the use of a violent kind of delightfulness if there is no pleasure in not getting tired of it. The question does not come before there is a quotation. In any kind of place there is a top to covering and it is a pleasure at any rate there is some venturing in refusing to believe nonsense. It shows what use there is in a whole piece if one uses it and it is extreme and very likely the little things could be dearer but in any case there is a bargain and if there is the best thing to do is to take it away and wear it and then be reckless be reckless and resolved on returning gratitude.

Light blue and the same red with purple makes a change. It shows that there is no mistake. Any pink shows that and very likely it is reasonable. Very likely there should not be a finer fancy present. Some increase means a calamity and this is the best preparation for three and more being together. A little calm is so ordinary and in any case there is sweetness and some of that.

A seal and matches and a swan and ivy and a suit.

A closet, a closet does not connect under the bed. The band if it is white and black, the band has a green string. A sight a whole sight and a little groan grinding makes a trimming such a sweet singing trimming and a red thing not a round thing but a white thing, a red thing and a white thing.

The disgrace is not in carelessness nor even in sewing it comes out out of the way.

What is the sash like. The sash is not like anything mustard it is not like a same thing that has stripes, it is not even more hurt than that, it has a little top.

A Little Called Pauline

A little called anything shows shudders.

Come and say what prints all day. A whole few watermelon. There is no pope.

No cut in pennies and little dressing and choose wide soles and little spats really little spices.

A little lace makes boils. This is not true.

Gracious of gracious and a stamp a blue green white bow a blue green lean, lean on the top.

If it is absurd then it is leadish and nearly set in where there is a tight head.

A peaceful life to arise her, noon and moon and moon. A letter a cold sleeve a blanket a shaving house and nearly the best and regular window.

Nearer in fairy sea, nearer and farther, show white has lime in sight, show a stitch of ten. Count, count more so that thicker and thicker is leaning.

I hope she has her cow. Bidding a wedding, widening received treading, little leading mention nothing.

Cough out cough out in the leather and really feather it is not for.

Please could, please could, jam it not plus more sit in when.

T.S. Eliot and the Humor of Adolescence

“I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each./ I do not think that they will sing to me.” These self-pitying lines from T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” are some of the most often quoted from this poem. In fact, Stephen Colbert quotes them in an interview with Elizabeth Alexander (see this recent post on Humor In America for the link). Colbert is convinced that the mermaids will sing for him, a confidence which causes his guest and audience to laugh. Colbert makes light of the speaker’s self pity, and his faux-innocent position seems refreshing.

“Prufrock” is a poem with a tone that seems to change over time––for the reader. Presumably resonant with all adolescent forms of urban angst and anguish (see this recent article in the New York Times about a man for whom the poem characterized a romantic sense of adolescence), “Prufrock” is really a silly poem the more one reads it. Yet silliness makes the poem richer and perhaps more profound than angst ever could. Colbert is right: it is ridiculous, even comically melodramatic to worry about whether or not the mermaids will sing to you––to worry about personal worthiness.

We are warned of the poem’s deadpan humor in the opening lines, which open classically with the line, “Let us go then, you and I…” and follow with a comparison between “the evening . . . spread out against the sky” and “a patient etherized upon a table.” Romantic vision and complete physical, social, and emotional inertness are juxtaposed. “Do I dare disturb the universe?” a voice in the poem wonders. Spontaneous boldness is not an option for this voice. Cowing and reticence and quiet observation of others are its modes.

We think of these personal characteristics in something of the same light that we view adolescence: brooding, sensitive, thoughtful, withdrawn. We rarely think of these states as funny. Yet coming back to “Prufrock” after adolescence has been over for many years is a humorous experience. Why should a love song about a man with a funny, unromantic name begin in Italian? We are already in parody here. The choice to rhyme “come and go” with “Michelangelo” is hilarious (“In the room the women come and go/ Talking of Michelangelo”). The choice to rhyme at all in a poem like this is worth a pause and a smile.

Noting parody and play in Eliot’s early poetry is nothing new. Drawing connections between the feline imagery here (“The yellow fog that rubs its back upon the window-panes,/ The yellow smoke that rubs its muzzle on the window-panes”) and Eliot’s later light-spirited cat poems is also nothing new. But it occurred to me the other day, as I watched ten teenagers work their way through this poem, that adolescence is rarely a state of being that inspires laughter. It inspires eye rolls, awe, and worry mostly, but not often overt chuckles of understanding. Perhaps we recognize the difficulty of the changes and uncertainties one faces at that age. Perhaps we shutter at remembering those difficulties.

Yet isn’t humor present in any cartoonish, shape-changing, awkward phase of life? Isn’t the comic persona fundamentally awkward and uncertain? The humor in “Prufrock” comes from the very same notes that strike adolescent readers as serious and true. Coming back to the poem after adolescence is over, one realizes that the awkward phase of life, though dramatically uncertain, was not very serious or permanent after all––nor did the self turn out to be as central to the drama as we thought. Just as Stephen Colbert hopes and Elizabeth Alexander encourages, the mermaids will sing to you if you want them to.

Humor in a Sonnet’s Essence

A friend and I have been puzzling about whether sonnets are, by nature of their form and conventions, essentially funny poems. Popular views of the sonnet are that this fourteen-line poem deals with unrequited love, lovesickness, heartbreak, relationship problems, or themes of political love—none of which seem like particularly funny topics on the surface. Yet so many poets have had a good time making fun of these very tropes, creating their own sonnet parody genre in the process. But in reviewing a handful of these mocking sonnets, I wonder if they reveal opportunities for humor in the sonnet form itself and, if we go back to the original poems they mock, perhaps subtler instances of humor in those ostensibly “serious” sonnets.

The sonnet parody is very simple: it makes fun of the sonnet’s rules and themes. About ten years ago, I had a short conversation at a poetry performance with the conceptual poet Kenneth Goldsmith. When he learned that I was interested in sonnets, he took out a piece of paper and with deadpan irony wrote out the following:

8

6

“That’s my sonnet,” he said (or something like that). His “joke” is based on the mathematical conventions of the sonnet, a poem which frequently contains eight lines that build in a certain direction (the octave) followed by six lines that resolve or release that theme (the sestet). Many poets poke fun at the technical strictures of the form, which John Keats went so far as to call “chains,” yet they were chains that he, along with William Wordsworth, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and Edna Saint Vincent Millay, found paradoxically freeing.

Goldsmith’s joke was not a put-down; I got the impression that deadpan irony simply underlies his poetic philosophy. A trailblazer in the intentionally humorous, newer art of conceptual and collage poetry, Goldsmith seems to find depth in the light play—and delight in the silliness—of the poetic arts. His tone is lighthearted, though, as I recall, and even affectionate towards the silliness.

Similarly, Billy Collins’s two sonnet parodies are at the same time love songs to sonnets. His poem “Sonnet” is itself a lesson in sonnet form:

Sonnet (2002)

All we need is fourteen lines, well, thirteen now,

And after this next one just a dozen

To launch a little ship on love’s storm-tossed seas,

Then only ten more left like rows of beans.

How easily it goes unless you get Elizabethan

and insist the iambic bongos must be played

and rhymes positioned at the ends of lines,

one for every station of the cross.

But hang on here while we make the turn

into the final six where all will be resolved,

where longing and heartache will find an end,

where Laura will tell Petrarch to put down his pen,

take off those crazy medieval tights,

blow out the lights, and come at last to bed.

-Billy Collins, The Making of a Sonnet, edited by Eavan Boland and Edward Hirsch (New York: Norton Anthology, 2008), 73.

“Come at last to bed” is a deceptively simple ending for the poem, one that exposes a problem in most sonnets—as well as an opportunity for humor. The problem: a sonnet is a piece of paper, an out-of-time meditation that stands in the way of two lovers meeting. Collins suggests that the poet’s writing keeps him from real contact with the beloved. Frequently, the sonnet’s speaker writes from a place of loneliness; real connection with the beloved, either physical or emotional, depending on the poem, is somehow blocked.

About half of William Shakespeare’s 154 sonnets deal with thwarted or frustrated love, precisely because final coupling is kept in suspense in the sonnet form, or deemed impossible. Yet the tormenting experiences of heartache, however agonizing in the moment, are so hackneyed in our literature that there emerges a kind of joke in their repetition. Consider this seldom-studied sonnet by Shakespeare:

Sonnet 120

That you were once unkind befriends me now,

And for that sorrow, which I then did feel,

Needs must I under my transgression bow,

Unless my nerves were brass or hammered steel.

For if you were by my unkindness shaken,

As I by yours, you’ve passed a hell of time;

And I, a tyrant, have no leisure taken

To weigh how once I suffered in your crime.

O! That our night of woe might have remembered

My deepest sense, how hard true sorrow hits,

And soon to you, as you to me, then tendered

The humble salve, which wounded bosoms fits!

But that your trespass now becomes a fee;

Mine ransoms yours, and yours must ransom me.

Love blows are used for bartering and ransoming in this poem, and are compared to an economic exchange or a wartime practice. The poet builds the tit-for-tat banter until it falls apart in a reductio ad absurdum: if both lovers owe one another for wrong doing, shouldn’t they just throw out their accounting books and open a new leaf? The middle of the poem, around the placement of what Collins reminds us is the Italian turn, or volta, is perhaps the one genuinely tender moment in the poem: “O! That our night of woe might have remembered my deepest sense, how hard true sorrow hits.” The rest of the poem, including the mutually negating ending, is a kind of game with its own implicit sense of the ridiculous. And the blame-and-shame game reveals itself to be, within the argument of this poem, absurd.

Uncharacteristic of Shakespeare, this particular sonnet has no obvious sexual imagery. Yet, back to Collins’s last line, the word “bed,” the very last word of the Collins poem, reminds us of another world of opportunity for humor in sonnets: their frequent and often awkward use of sexual innuendo. John Updike’s conceptual sonnet parodies this truth:

Love Sonnet (1963)

In Love’s rubber armor I come to you,

b

oo

b.

c,

d

c

d:

e

f——

e

f.

g

-John Updike, The Making of a Sonnet, 328.

In his book on poetic form, Paul Fussell likens the movement from octave to sestet in the Petrarchan model to sexual arousal and release. The topic is treated with seriousness and a sense of the erotic in many examples (consider Robert Frost’s sonnet “A Silken Tent,” which can be read as a metaphor for arousal and at the same time a commentary on the pressure and release contained within sonnet form), yet this is the very trope that poets later parody. As Updike’s minimalist commentary seems to suggest, the sonnet, when stripped of its elegant imagery and rhymes (Updike retains just the rhyme coda), is no more than an adolescent reverie about sex. With its flowery language shed, a kind of funny silliness is uncovered in the sonnet form, a form which dates backs nearly a millennium. (The Tumblr site “Pop Sonnets”, which comically turns Taylor Swift, Beyoncé, and Snoop Dog songs into Shakespearean sonnets, speaks to the pop-song romance of the sonnet.)

Yet most great sonnets are about more than adolescent ideas of sex, and their humor is also at times more complex. William Carlos Williams, who resisted writing sonnets for a long time, finally came up with his own somewhat comic offering:

Nude bodies like peeled logs

sometimes give off a sweetest

odor, man and woman

under the trees in full excess

matching the cushion of

aromatic pine-drift fallen

threaded with trailing woodbine

a sonnet might be made of it

Might be made of it! odor of excess

odor of pine needles, odor of

peeled logs, odor of no odor

other than trailing woodbine that

has no odor, odor of a nude woman

sometimes, odor of a man.

Whether this is a sonnet, formally speaking, is debatable. Like Updike, Williams seems to strip the poem down to sensory and sensual details, so bare in fact that they lose their erotic context and become, just a little, funny.

But humor seems to be a key element of the tender––and ubiquitous––humiliation that underlies all love stories, happy or sad. The lover must become ridiculous and submit to a ridiculous pattern of longing, as unsexy as it is concerned with sex. Consider Gertrude Stein’s approach to the sonnet. Her “Sonnets That Please” distill the form to the essence of the lovers’ banter, and we see, as we do looking closely at all of these examples, the inherent humor in what it means to be in love—the age-old pattern of heartbreak and heart yearning to which we give ourselves, in spite of humiliation. The humanity of it, the regularity of it is as tender as it is recognizable and therefore, somehow, funny.

Sonnets That Please (1921)

How pleased are the sonnets that please.

How very pleased to please.

They please.

Another Sonnet That Pleases

Please be pleased with me.

Please be.

Please be all to me please please be.

Please be pleased with me. Please please me. Please please please with me please please be.

-Gertrude Stein, Bee Time Vine (Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1953 and 1969), 220.

Jack Kerouac’s American Haiku

Rue Gît le Coeur: street where lies the heart. On a tiny street in Paris, about a quarter of the length of a New York City block and just a little wider than a Venice passageway, lies a minuscule hotel. Its rooms, replete with medieval-era wooden beams and matching pastoral designs on the wallpaper and curtains, are just as tiny; only one person can move around in the room at a time. The elevator, too, can manage only one person per trip. Charming and minute, there is no space in this hotel for oversized couches and exercise rooms; there is barely space enough to stretch out your arms and yawn, let alone sing.

When I visited this sequestered street last year—almost hidden in the midst of a crowded tourist district—I was amused and surprised to see the plaques, figured prominently on the hotel’s front façade, and the photographs displayed proudly in the lobby, honoring several Beat-era poets who had stayed there more than half a century ago. According to one of the plaques, William S. Burroughs supposedly wrote Naked Lunch there.

This hotel is to architecture what haiku is to literature: charming, ancient, and airtight—“no room for petty furniture,” as Emily Dickinson writes of compressed poetry. If there is a general view of Beat-era poetry, it is that it rides the force of Whitman’s barbaric yawp and delights in expansiveness, open vistas, and freedom. So it is a little unexpected and amusing to imagine multiple Beat poets writing productively in this very cozy, well-appointed hotel, just as there is something unexpected about the Beat poet who ventures into the space of haiku.

Jack Kerouac did not join his colleagues at this hotel, but he did spend considerable time within the small chamber of the haiku, testing its edges, poking fun at its purpose, and stumbling into very sweet encounters with its essence. Yet what stands out in his playful attempts with the form (which he renamed “Pop”) is their humor.

In his Book of Haikus, edited in 2003 by Regina Weinreich, Kerouac toys with nature. In the Japanese tradition of seventeenth-century poet Matsuo Basho, haiku juxtaposes something man-made with something from the natural world. Generally in Basho’s poetry, nature complements if not soothes loneliness.

Basho:

494.

drinking saké

without flowers or moon

one is alone.

(Matsuo Basho, The Complete Haiku, translated by Jane Reichhold (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 2008)

However, in Kerouac’s haiku, man and nature collide, confront one another, or fumble towards connection.

Kerouac:

A raindrop from

the roof

Fell in my beer

(New York: Penguin Poets, 2003), 30

Where Basho’s natural elements blend with or serve to illuminate the human situations in his haiku, Kerouac’s speakers sometimes come off as annoyed with nature.

Basho:

669.

don’t be like me

even though we’re like the melon

split in two.

Nature is a not a metaphor in Kerouac’s haiku, but an encounter—even a clash:

Kerouac:

Bee, why are you

staring at me?

I’m not a flower!

(15)

The earth winked

at me—right

In the john

(10)

In his imitations of the Japanese model, Kerouac produces humor by reversing the direction of the metaphor: human experience is no longer compared to something beautiful in nature; rather, nature interferes with or is pitted against man-made entities.

Lovers and Fools in the Modern Romantic Comedy

Can lovers ever really be fools? Can fools really lose themselves in romantic love? The lover and the fool are comic literary archetypes, but they are funny in very different ways. Lovers in romantic comedies typically exhibit buffoonish humor; these movies are funny at the expense of their protagonists. We think their counter-times and missed messages are humorous for the clumsiness and coincidence they reveal, but the characters do not “know” that their experiences seem funny. Hugh Grant’s romantic anxieties must be genuine anxieties for his character in order to be funny to his audience. Even Shakespeare’s Kate from The Taming of the Shrew must be sincere in her impetuousness for her audience, guided by a humorous theatrical interpretation, to find them outrageous and funny. But she is never laughing—her position is quite the opposite of amused, in fact.

The fool seems different. Fools know they are speaking in wit and riddle, and they are disinterested players without a personal stake in the interpersonal dramas before them. Shakespearean fools are often androgynous; they do not meddle, at least with any personal agenda, in human passions. King Lear’s fool makes the crudest, even the most scathing jokes, yet he is “boy” to Lear, and sometimes he is even played by the same actress who portrays Lear’s daughter Cordelia.

Hamlet has a touch of the fool; in fact, the court jester Yoric is one of the only personalities he respects in the play. I have sometimes wondered if the impossibility of his relationship with Ophelia has to do with his changing role from lover to fool. It seems he cannot be both at the same time. If the courtiers think Hamlet’s out of his mind, then they cannot at the same time think he is fit to marry Cordelia. As a fool he is somehow ineligible for romantic courtship.

Can there ever be a fool-type presence in romantic comedies? For a moment I wondered if the protagonist’s best friend or neighbor might embody the fool. I had in mind Rhys Ifans’s in Notting Hill, but he too is a buffoon as opposed to a knowing riddler, and he too eventually finds love.

Actually, the traditional fool bears a closer resemblance to the stand-up comedian, who is part court jester, part truth speaker, and in those respects the stand-up comedian is a derivative of the Shakespearean fool archetype. Although the stand-up comic’s jokes extend to areas of sexual life that no one else will touch, the comic often also mocks or cynically rejects his or her own romantic prospects. Louis C.K.’s brash jokes about his wife are in some sense a testament to this. When the wife became ex-wife, the jokes seemed more shocking in retrospect. But is it too much to say that the unattached comedian was then freed to become an even more disinterested player? Maybe.

Some stand-up comedians (Steve Martin, Michael Keaton, and Bill Murray come to mind) explore the lover’s role with success, but this only works if they change hats. It seems the lover cannot know that he is the one telling jokes; he must become the joke. He must surrender to the humiliating experience of being in love. One exception might be Groundhog Day (1993), where only the protagonist and the audience understand why this courtship through repetition is funny; and Murray’s lover-protagonist is not sure, until late in the film, that he wants to cultivate any lasting personal ties.

Traditionally, the court jester is in but not of society. It is his detached stance in the drama of life that gives the fool license to say things no one else can say. He must genuinely appear to have nothing to gain and nothing to lose.

When the stand-up comedian stays court jester and also tries to be the lover, the results are confusing—but interesting. Consider Chris Rock’s Top Five, which contains some of Rock’s most experimental and wild tangents into the sexually outrageous (I was reminded of a Laurence Sterne novel) as well as some of the rom-com genre’s more stilted courtship moments. The film represents vibrant new terrain for Rock, but it does not leave one feeling confidant that the stand-up comedian can seamlessly hop from comedy stage to lover’s lair.

Yet Rock’s new genre within the romantic comedy genre could represent a broadening shift for the fool. Unlike Hamlet, Rock’s protagonist is presented with a love interest, Rosario Dawson, who prizes the fool over the lover. In turn, Rock’s languishing stand-up comedian character finds new inspiration through love. It is a transition in progress to be sure, but perhaps these once distinct archetypes are merging into a single character. Perhaps the lover is becoming a little savvier and the fool just a little more tender.

“Can I get to that heart? Can I get to that mind?”A tribute to the frank, contested humor of intense teachers—and to Henry Higgins

Nine years ago in my first class in graduate school, a course on approaches to teaching writing, we read George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion as a break from composition theory. I was thrilled, but I reigned in my enthusiasm when I noted that others in the class, including my professor who I respected immensely, felt apologetic about the book. Words like abusive and misogynistic were thrown casually around the seminar table, as they sometimes are in graduate seminars. Why was there this worry about the teacher in the story—about Henry Higgins? I was surprised that so many disliked his method because I had always thought of him as an effective teacher. My only real support for this inkling was that I found him . . . funny.

Did I have this wrong and, if so, what was the source of my misunderstanding? Or, if I was right that Henry Higgins was a funny and therefore benevolent man (I had collapsed the two conditions in my mind), what caused the confusion among others in my graduate school class? Why had everyone else failed to note his humor? And what did I see in his humor anyway? Could it be that I thought his humor lightened—or even completely neutralized—his seemingly harsh dealings with Eliza Doolittle? Or did we all have it wrong? Did a “correct” reading of the play really fall somewhere in the middle—was it really that Higgins was both funny and harsh? I began to doubt my first intuition about professor Higgins, as I seemed to be faced with a more complicated story.

The irony was that my own professor in this class, a good man with a fiery heart, who was, that very semester, dying of cancer (this would be his last seminar on teaching writing), was a gruff man himself. He and Henry Higgins shared a vocational intensity. In fact, like Henry Higgins, this professor had made it his life’s work to teach writing (or “speech”) to the underserved, hugely advancing the trend in what is now called “access” education at top universities. He was passionately focused on this until his last breaths—and he was passionately focused on us, his students; he read our final papers days before he died. Although we, his students, didn’t have a personal rapport with him—we would never have imagined going out for a beer with this man—our engagement with theories of speech and writing, particularly where low-income populations were concerned, kept him alert, stubborn, and justifiably cranky until the end.

Langston Hughes on Hard Laughter

Langston Hughes’s roughest book of poetry is also an homage to laughter.

In 1925 Langston Hughes lived with his mother on the north side of S Street, a few short blocks from Dupont Circle in Washington, D.C. The tiny two-story square row home, painted in deep brown trim today, is set back from the sidewalk. A meandering path leading up to the house meets, at the sidewalk’s edge, the meandering path of the house next door; they bend together in the rough shape of a heart. The first story of the home has a large single window, broad and revealing like a storefront display. The second and top story, where Hughes most likely lived and wrote, seems squat, pared down, resting atop the broad window. The house itself is inconspicuous, quiet, and low––slyly hidden by the grander-seeming homes surrounding it.

Langston Hughes lived in many places during his pivotal year in Washington, but, walking by this house one day recently, I found myself wondering if it was here that the seeds were planted for his 1927 book of poems, Fine Clothes to the Jew, a book famous among a small group of scholars for its controversial release but that remains unknown to many.

Langston Hughes lived in many places during his pivotal year in Washington, but, walking by this house one day recently, I found myself wondering if it was here that the seeds were planted for his 1927 book of poems, Fine Clothes to the Jew, a book famous among a small group of scholars for its controversial release but that remains unknown to many.

Today the book is out of print. Google Books does not “preview” it, most libraries do not carry it, and even The Library of Congress cannot locate their lone copy. A small number of first editions are available on-line for upwards of a thousand dollars. The book is worth far more. (Two Collected Works of Langston Hughes editions, Arnold Rampersad’s and Dolan Hubbard’s, contain the poems from Fine Clothes to the Jew.) The book received scathing reviews when first released, mostly from Hughes’s fellow literati in Harlem, for its seemingly unabashed and degrading depictions of African Americans.

In situation and appearance, Langston Hughes’s mother’s home resembles the paradox in the reception history of Fine Clothes to the Jew. The house is removed, easy to miss, simple, and confined in the heart of a bustling city. Yet the house is also solid and stern, its gazing window luminous. Likewise the poems in this book are hard, describing people who live hard lives in the brusque city or lonely, rural south. Actually, written in six parts alternating between the city and the country, Fine Clothes doesn’t describe these people; rather, each poem is spoken in the voice of a different, struggling soul—the prostitute, the pimp, the abusive husband, the abused wife, the player, the played, the child, the worried parent, the broken-hearted, and the philanderer—to name just a few of the characters. A burdened consciousness of race and ethnicity is made overt notably in the book’s title, which pairs beauty or opulence (fine clothing) with the ugliness of bigoted social perceptions.