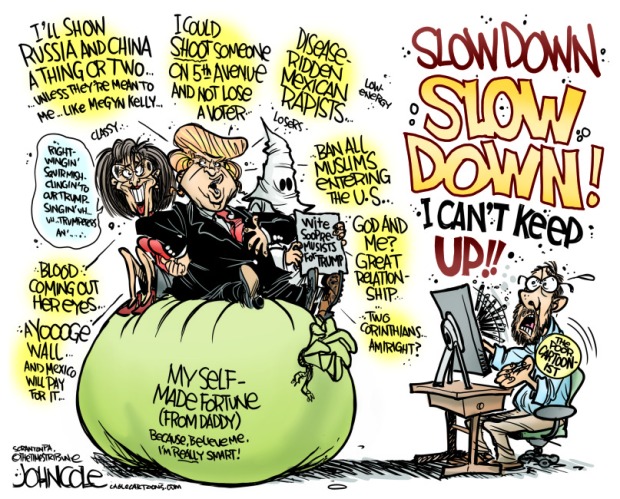

Bill Burr: A Safe Space for Standup?

Maybe I’ve been watching too many political debates or reading too many articles that pop up as newsworthy on my social media newsfeed (i.e. Starbucks’ Cupgate) – either way, I’ve been craving some authenticity lately and jumped at the chance to see comedian Bill Burr and his borderline-obnoxious-yet-refreshingly-honest standup last week.

My affinity for Bill Burr started years ago when I stumbled upon Bill Burr’s Monday Morning Podcast. Since 2007, Burr has relied heavily on material about sports, food, stereotypes, and even consumer complaints to air out his grievances in his weekly podcast, a part of the All Things Comedy network. During a recent episode on a Thursday night, Burr discussed his upcoming trip to Philadelphia, home of the world’s best cheesesteaks, where I saw him at the Wells Fargo Center, his largest live crowd ever, the following evening. If you’re not familiar with Bill Burr, his role during the second season of Chappelle’s Show might be worth a watch. Or you can catch the Massachusetts native on one of his specials – 2014’s I’m Sorry You Feel That Way being the most recent. Burr’s newest project, F is For Family, airs on Netflix next month.

As I was leaving the show, a group of 3 or 4 women in front of me lamented about giving up a Friday night to attend a show highlighting “another sexist comedian.” They cited his shtick about women’s takeover of the NFL as proof of their supposition. Below, a sample:

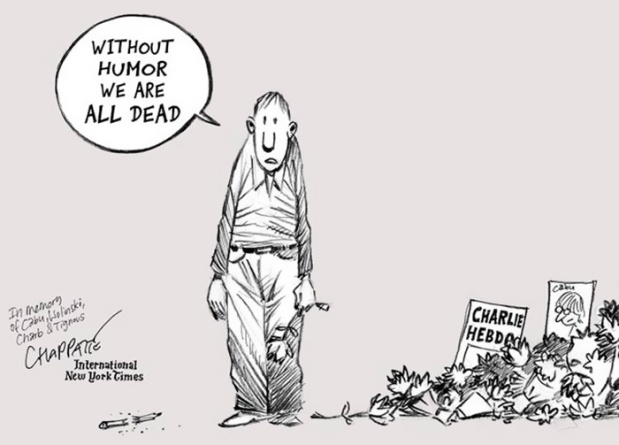

Charlie and Louie: An Affair of Two Magazines, Two Cities, and Too Many Questions

Je suis Charlie Hebdo, et aussi Michel Brown, et aussi Darren Wilson et aussi… As Teresa Prados-Torreira recently observed in this space, the last month has seen an international slurry of reactions to the Charlie Hebdo Massacre from outraged officials, scampering journalists, erstwhile academics, dedicated peace-keepers, and, of course, the international community of artists, cartoonists, and satirists. Prados-Torreira astutely summarizes in her 20 January post, “at first glance, it seems obvious that the answer to this dilemma should be a wholehearted affirmation of the need to stand in solidarity with the French magazine, with the murdered cartoonists, and in support of free speech. But the content of Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons, their irreverent depiction of Mohammed and Muslims, have resulted in a cascade of critical essays online and elsewhere.”

Many have since noted that, for interpreters within and beyond French culture, the magazine’s scabrous treatment of all things sacred and sanctified could be labelled either courageous or irresponsible depending upon personal preference. One thing is certain, though, Charlie Hebdo was rarely, if ever, about discretion. Even more interestingly, a new angle on the extensive media coverage of the attacks has taken shape that inquires as to why the tragic murder of several talented artists has become, either incidentally or on purpose, a larger global issue and a much more public and popular rallying point than the rampant cruelties taking place in Nigeria involving Boko Haram?

Even more interestingly, we have to admit that slander, satire, and ridicule of Arabs, Muslims, and Islam are hardly rare in America mainstream culture. Consider the skirmishes that erupted over the years surrounding Johnny Hart’s abuse of Islamic and Judaic symbols in several episodes of his comic strip, B.C., especially the “potty humor” episode that fused the sacred icons of Islam with the half-moon of an outhouse door. Is this not Charlie Hebdo territory? With the rhetorical avalanche surrounding Charlie Hebdo just beginning to settle, we might wonder if any more discussion could possibly serve to alleviate the tension, fear, and uncertainty that has seemingly spread across an outraged global public.

It’s a very fair question, but instead, I would like use the terror attacks in France, and their subsequent influence, to explore a few more local and personal concerns about the deploying of satire, the power of cartoons, and the often unexpected inaccuracies of visual wit. Since the assault on the Charlie Hebdo offices, there have been several inspiring statements of solidarity and strength in support of free speech and equal opportunity insult, most notably including the great public demonstrations in Paris, throughout France, and across the world.

Can there ever be a more heartening and honest sign that humor – especially in its most relentless, hostile form – deserves our attention, respect, and scrutiny? There have also been a wide variety of high profile reactions and commentaries throughout the intellectual honeycomb of bloggers, critics, and scholars. Much has been made of Joe Sacco’s somewhat disappointing Guardian catechism “On Satire.” Important statements have also arisen from doyens of provocative comics including Art Spiegelman, Keith Knight (who produced two suitably irreverent texts from very different perspectives), and Steve Benson, among many, many others. Scholars also have contributed valuable and sometimes revelatory insight into the complex legacy of French cartooning and its contribution to both Charlie Hebdo’s editorial policies and the violent reactions that it frequently instigated. Bart Beaty and Mark McKinney have offered reasoned and informative assessments that went largely ignored in the media frenzy following the attacks. Even richer and more comprehensive studies of the violent potential of editorial cartooning have also arisen from astute historians like Paul Tumey and Jeffrey Trexler. Cartoonists, of course, have been at the vanguard of the fight for freedom of speech, recognition, and reaction. From the very moment that news of the attack broke in France, powerful responses like this one were quickly finding their way around the world’s webs.

The translation is simply, “The ducks will always fly higher than the guns.” This seems a fitting commentary on everyone’s natural right to free speech, peaceful tolerance, and artistic expression but for the French reader, as I have come to understand it, the cartoon also includes sly references to the enduring poignancy of journalism and the relative pointlessness of murder, terror, censorship, and repression. As far as I know, this cartoon comes from the first wave of responses to the assault on the Charlie Hebdo offices.

“Can I get to that heart? Can I get to that mind?”A tribute to the frank, contested humor of intense teachers—and to Henry Higgins

Nine years ago in my first class in graduate school, a course on approaches to teaching writing, we read George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion as a break from composition theory. I was thrilled, but I reigned in my enthusiasm when I noted that others in the class, including my professor who I respected immensely, felt apologetic about the book. Words like abusive and misogynistic were thrown casually around the seminar table, as they sometimes are in graduate seminars. Why was there this worry about the teacher in the story—about Henry Higgins? I was surprised that so many disliked his method because I had always thought of him as an effective teacher. My only real support for this inkling was that I found him . . . funny.

Did I have this wrong and, if so, what was the source of my misunderstanding? Or, if I was right that Henry Higgins was a funny and therefore benevolent man (I had collapsed the two conditions in my mind), what caused the confusion among others in my graduate school class? Why had everyone else failed to note his humor? And what did I see in his humor anyway? Could it be that I thought his humor lightened—or even completely neutralized—his seemingly harsh dealings with Eliza Doolittle? Or did we all have it wrong? Did a “correct” reading of the play really fall somewhere in the middle—was it really that Higgins was both funny and harsh? I began to doubt my first intuition about professor Higgins, as I seemed to be faced with a more complicated story.

The irony was that my own professor in this class, a good man with a fiery heart, who was, that very semester, dying of cancer (this would be his last seminar on teaching writing), was a gruff man himself. He and Henry Higgins shared a vocational intensity. In fact, like Henry Higgins, this professor had made it his life’s work to teach writing (or “speech”) to the underserved, hugely advancing the trend in what is now called “access” education at top universities. He was passionately focused on this until his last breaths—and he was passionately focused on us, his students; he read our final papers days before he died. Although we, his students, didn’t have a personal rapport with him—we would never have imagined going out for a beer with this man—our engagement with theories of speech and writing, particularly where low-income populations were concerned, kept him alert, stubborn, and justifiably cranky until the end.

Marc Maron Mania

It is time to jump on the Marc Maron bandwagon. Really. Do it right away because, well, things could go bad at any moment. I know this because I have been following Maron for almost six months now. Six months of unadulterated laughter at a guy who builds his material on the core fact of his life: things could go bad at any moment. Maron is having a good year in the public realm. He is making money and getting praise from critics and new fans alike. And it is all deserved. He is provocative (which means he is funny but pisses people off) and likable (which means that he is funny but people feel sorry for him). Maron has already earned some attention on HA!. For two excellent pieces, see: Matthew Daube on Marc Maron; ABE on Marc Maron.

He is cooking on all burners, putting out wonderful material in the last couple of years: Thinky Pain, an album and concert video on Netflix) and This Has to Be Funny being released in August 2014, Attempting Normal, a book with solid praise thus far, and Maron, the wonderful television show in its second season on IFC and available on Netflix.

Maron on his youth baseball experience from Thinky Pain

Here is a brief scene from the sitcom Maron as he interviews C.M. Punk: Interview with C.M. Punk on Maron

He is an overnight twenty-five-years-in-the-making success. And the time to jump in an enjoy this dynamo is now because, well, who knows what is around the corner? He’s just a guy trying to be an adult, OK? Sometimes it goes well. Sometimes, not so well. Maron has found a way to make his pain pay. (He just got $ 4.99 from me for a premium membership of WTF). The podcast started in 2009 and still runs out of his garage. In spite of this humble setting (or related to it, perhaps), Maron draws in some of the biggest stars of comedy and Hollywood, as well as in the music industry. Here are a few of his guests just from the last few months: Josh Groban, Billy Gibbons, Vince Vaughan, Ivan Reitman, Lena Dunham, Laurie Kilmartin, and Will Ferrel, and so on. WTF is an ideal text for studying the state of American humor. I would consider it a valuable (perhaps essential) forum for anyone interested in studying/learning the craft of American stand up comedy and its interdependence on all facets of American pop culture, especially music.

Over the last several years, Maron via WTF has steadily put together a remarkable collection of interviews of some of the best comic minds of our time, along with a wide array of other artists of varying interests. If you have yet to listen to WTF, well, wtf?

Just this past week, WTF hit its 500 podcast. Here is a link to a list of the episodes and the guests: WTF Episode Guide. The most recent 50 are available free via the the app or online here: WTF Podcast Home

Rolling Stone (Rolling Stone Article) listed Maron as on The 10 Funniest People, Videos and Things of the Coming Year in 2011. In this brief article, Jonah Weiner calls Maron an “acid-tongued rage-prone satirist.” That is just the thing. Maron causes critics to use hyphenated terms to describe him. He is THAT good. Actually, Weiner makes the right call as he talks about WTF as his most important work to date. He calls it a “series of unvarnished shit-shoots with comedians that move from laugh-geek joke autonomy to quasi-therapeutic venting.” Geez, three more hyphenated terms in one sentence. Do you see what Maron can do? I did not know how important hyphens were to Rolling Stone, but I digress. Underneath the god-awful (hyphen!) phrasing of the description is a crucial point.

WTF balances formidable discussions of the craft of humor (what Weimer calls “joke anatomy”–what? no hyphen?) and psychoanalysis, all of which teeters on disaster at any given moment, and all of it thoughtful. Marc Maron is a funny comic writer; he is solid performer in his sitcom; and he is compelling on stage, but he is a master of the interview. He does not know why. In the 500 episode he acknowledges the praise for his interviewing skill but seems baffled by how it came about. It reminds me of the anecdote about Bob Newhart, a master of stammering timing. Newhart, when asked how he managed to so perfectly create the illusion of talking on the phone, for instance, responded that he simply waited the amount of time it would take for someone on the other end of the fictional conversation to say something. Brilliant. Newhart deflects any praise for his skill and pretends that his timing is innate and open to anyone. Nah. Newhart has it; Maron has it, too. It has something to do with talent, but it is also a work in progress. In either case, Maron comes across as genuinely curious about how his guests struggle with craft (whether it is comedy, music, acting, writing, whatever) AND their inner demons. And he gives them the space to explore the humor and challenges of both. He also makes them talk about his own issues. Maron has issues.

In the New York Times (Jan. 2011; NYTimes Article on Maron), calls him “angry probing, neurotic and a vulnerable recovering addict.” Well, American comedy, right? He has been called a mix of Woody Allen and Lenny Bruce, which is both accurate and too easy. As he states in his introduction provided on the WTF website, he prefers the combination one of his fans provided: an Iggy Pop Woody Allen. Yes, American comedy of anxiety with a punk ethos. To give you a taste of this Maron mix, note the following three quotes included in the banner for the “about” section of the WTF website:

–“TV is great because no one knows when to retire and you can watch the full arc of success, sadness and decay.”

–“I’m glad to be part of the war on sadness. I’m a part time employee of the illusion that keeps people stupid.”

–“In most cases the only difference between depression and disappointment is your level of commitment.”

It’s time to jump on the Marc Maron bandwagon with a deep level of commitment. I just paid five bucks for premium access for the next six months. And I am looking into a 20 dollar mug.

The Trouble Begins at Nine?: Mark Twain, “A Speech on Women,” and Blackface Minstrelsy

“Trouble,” as I may have said once or twice, was Twain’s trademark.

On 11 January 1868, Mark Twain was asked to give a speech (printed in full below) responding to a toast at the Washington Correspondents’ Club. The toast: “Woman, the pride of the professions and the jewel of ours.”

John F. Scott, ed. New York: Dick & Fitzgerald, 1868. Collection of the author.

The speech was well received and widely re-published in newspapers — and also in an 1868 book called Brudder Bones Book of Stump Speeches, and Burlesque Orations, which contains a variety of humorous speeches and sketches from the blackface stage, variety houses and the lecture circuit, all indiscriminately mixed together. Twain, though, is given special recognition in the text, being referred to as “the celebrated humorist.”

While Twain was initially tickled both by his speech and its coverage in the press — and even sent a copy to his own mother, who apparently loved it — he later worried about whether the speech was too vulgar in places. In the various reprints, it would seem that some editors agreed with him, as they omitted bits here and there. Their choices are interesting.

The Washington Star version (13 January 1868), for example, mildly says that Twain “responded” to the toast. It omits an off-color reference to wives cuckolding their husbands and bearing others’ children and an appreciative tribute to Eve in the pre-fig-leaf days.

Brudder Bones, on the other hand, offers that Twain “was called upon to respond to a toast complimentary to women, and he performed his duty in the following manner.” The book changes that “manner” a bit, by striking the final, conciliatory paragraph that puts all “jesting aside” with a toast honoring each man’s mother. Brudder Bones also omits Twain’s stated desire to “protect” women, apparently not seeing this as necessary or appropriate, or perhaps funny. Like the Star, the minstrel show version omits the reference to women’s infidelity and the children that arise from it, but reprints in full the appreciation of Eve, which celebrates female beauty and sexuality.

But for Twain enthusiasts and scholars, Brudder Bones also includes another item of interest. It is well known that Twain advertised his lectures with various versions of the phrase “The Trouble Begins at Eight.” And his favorite blackface minstrel troupe, the San Francisco Minstrels, also used variations of the same phrase to advertise their shows for almost two decades, an association Twain seemed to enjoy — and certainly never complained about. Brudder Bones, though, confirms that both Twain and the San Francisco Minstrels likely had an earlier source for that particular phrasing. The 1868 book includes a sketch written and performed by blackface minstrel, entrepreneur, and promoter Charley White — De Trouble Begins at Nine, as played at the American Theatre, 444 Broadway. This theatre burned to the ground on 15 February 1866, according to theatre historian George Odell (VIII.84).

But for Twain enthusiasts and scholars, Brudder Bones also includes another item of interest. It is well known that Twain advertised his lectures with various versions of the phrase “The Trouble Begins at Eight.” And his favorite blackface minstrel troupe, the San Francisco Minstrels, also used variations of the same phrase to advertise their shows for almost two decades, an association Twain seemed to enjoy — and certainly never complained about. Brudder Bones, though, confirms that both Twain and the San Francisco Minstrels likely had an earlier source for that particular phrasing. The 1868 book includes a sketch written and performed by blackface minstrel, entrepreneur, and promoter Charley White — De Trouble Begins at Nine, as played at the American Theatre, 444 Broadway. This theatre burned to the ground on 15 February 1866, according to theatre historian George Odell (VIII.84).

So . . . the trouble actually began at nine — nine to ten months before Twain’s inspired first use of a variation of the phrase.

And now, let’s take a look at the mild trouble Twain stirred up about women at the Correspondents’ Club, trouble that he felt that “they had no business” reporting “so verbatimly.” For those who appreciate Twain’s later 1601, this “trouble” will seem tame indeed, but it does have its charms:

**********************************************************

A Speech on Women by Mark Twain

Washington Correspondents’ Club, 11 February 1868

MR. PRESIDENT: I do not know why I should have been singled out to receive the greatest distinction of the evening — for so the office of replying to the toast to woman has been regarded in every age. [Applause.] I do not know why I have received this distinction, unless it be that I am a trifle less homely than the other members of the club. But, be this as it may, Mr. President, I am proud of the position, and you could not have chosen any one who would have accepted it more gladly, or labored with a heartier good-will to do the subject justice, than I. Because, sir, I love the sex. [Laughter.] I love all the women, sir, irrespective of age or color. [Laughter.]

Human intelligence cannot estimate what we owe to woman, sir. She sews on our buttons [laughter], she mends our clothes [laughter], she ropes us in at the church fairs — she confides in us; she tells us whatever she can find out about the little private affairs of the neighbors ; she gives us good advice — and plenty of it — she gives us a piece of her mind, sometimes — and sometimes all of it ; she soothes our aching brows; she bears our children — ours as a general thing. In all the relations of life, sir, it is but just, and a graceful tribute to woman to say of her that she is a perfect brick.1 [Great laughter.]

Wheresoever you place woman, sir — in whatever position or estate — she is an ornament to that place she occupies, and a treasure to the world. [Here Mr. Twain paused, looked inquiringly at his hearers and remarked that the applause should come in at this point. It came in. Mr. Twain resumed his eulogy.] Look at the noble names of history! Look at Cleopatra! — look at Desdemona! — look at Florence Nightingale! –look at Joan of Arc! –look at Lucretia Borgia! [Disapprobation expressed. “Well,” said Mr. Twain, scratching his head doubtfully, “suppose we let Lucretia slide.”] Continue reading →

In the Archives: Edgar Allan Faux (1877 then 1845)

They say humor is based on timing. Yes, as is everything else. Ask Elisha Gray about telephone patents. I was plugging along, working on a piece about the comedian Dana Gould, and still figuring out when I would finish writing about Mark Twain and the German language, when an article in my local newspaper caught my attention:

“Dead Poets Society founder visits 300th grave”

The fact that there’s an actual Dead Poets Society prompts visions of Ethan Hawkes’s teeth and an involuntary desire to kill Robert Sean Leonard. Swallowing my bile I learned that the current founder, Walter Skold of Freeport (Maine), has visited the gravesites of 300 poets “ahead of this weekend’s fourth annual Dead Poets Remembrance Day.”

What is “Dead Poets Remembrance Day”? Apparently, “with the help of 13 current and past state poets laureate,” Skold was able to dedicate October 7—“the day that Edgar Allan Poe died and James Whitcomb Riley was born—to heightening public awareness of the art of poetry.

The article posted October 5. That was Saturday. Making the actual memorial day a Monday. Today. My day to submit. So in honor of dead poets everywhere (and as one who writes the occasional verse and considers the artform dead, and therefore all practitioners the undead) let us examine the two poets tied to this day. What the article does not share is an appreciation for not just the day, but the year. On October 7, 1849, as Edgar Allan Poe lay dying of possibly drunken Rabies in a Baltimore medical college, James Whitcomb Riley was borning in Greenfield, Indiana.