More Cowbell and Teaching American Humor

I have a fever for exploring the curious life of one of the most bizarre and compelling comic sketches to work itself into the American grain, the collective unconsciousness, cultural zeitgeist, internet meme-life, and merchandising half-life: Saturday Night Live’s (SNL) “More Cowbell,” first shown on 08 April 2000. According to Wikipedia (yes, “More Cowbell”–the catch phrase–has its own page), “the sketch is often considered one of the greatest SNL sketches ever made, and in many ‘best of’ lists regarding SNL sketches, it is often placed at number one [citation needed].” I don’t understand why Wikipedia wants a citation for this statement; we don’t need any stinking citations for something that is so clearly and indisputably true. I have a “More Cowbell” app on my phone to prove it.

Here is a link to the sketch itself: More Cowbell Full Sketch

The sketch, written by Will Ferrell, is inscrutable and inexplicable, which makes it a perfect tool for teaching American humor. In the introductory days of a class I teach called American Popular Humor, I have always included contemporary sketch comedy as a way to get students to explore what makes humans laugh and also to break down that laughter into components. In short, I ask them to dissect the humor. It is what teachers do, with apologies to the damage inherently done to the sheer joy provided by humor itself.

I have found that “More Cowbell,” provides an ideal source for exploring the layers of humor in any given piece of material. The sketch offers the complexity of T. S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” That is a joke with its own layers (which is what humor scholars say when a joke is not as funny as they think it should be). Actually, most of Eliot’s poetry is a bit more complicated that a Will Ferrell SNL sketch, but almost nobody cares, and nobody wears a t-shirt with “More Prufrock” on it. If I am wrong about that, I am sorry–and saddened, as I gaze at my own rolled-up slacks. If I am the first the come up with that idea, I freely grant full licensure to anyone who wishes to make such a shirt. Surely, there are a few English grad students who would scrounge enough money together to buy it.

But “More Cowbell” as both a fine example of American humor and a cultural phenomenon provides a useful and fun way to talk about humor and how laughter depends on some many tenuous moments. Students bring much to such a discussion built around “More Cowbell,” because they are familiar with it and recognize its references. With that in mind, a discussion of the sketch can lead to a stronger awareness of how the humor of any given sketch depends on far more than the quality of the writing and performances. The context is the thing.

First, the sketch is funny in and of itself. It is built around simple incongruities, most obviously regarding the overblown attention that a simple instrument like a cowbell earns in the production of a rock song., in this case, “(Don’t Fear) the Reaper” by Blue Oyster Cult. The supposedly famous producer–the Bruce Dickinson, played by Christopher Walken, creates the first true comic moment of the bit by pronouncing his desire for “more cowbell.” This is incongruous–and funny–because anyone who has ever listened to the song would be hard-pressed to argue that it needs more cowbell. But even so, those hearing the song opening measures for the first time can recognize how prominent the cowbell is along with the dominating physical presence of Will Ferrell (as “Gene Frenkle,” the fictional lead cowbell player). That is the core written joke of the sketch: a great producer has a curious (and absurd) passion for more cowbell. Additionally, the sketch is an astute parody of the silly hyper-seriousness afforded to rock bands and their recording processes; the sillier-still seriousness of the VH1 rockumentary as a medium. All of this makes the sketch funny but alone is certainly not enough to earn or explain its legendary status. No, that comes from the live performance and the audience’s willingness to embrace the intangibles of the sketch. This is the point I am eager for students to embrace–the essential interaction between comic performances and audience desire.

“More Cowbell” is a funny bit that becomes hysterically funny in the moment based on the live performance. Students generally first assert that they enjoy the laughter of the actors on stage. This has been a key to the success of SNL from the beginning: audiences love when a performer breaks character and laughs–or, more appealingly, tries to suppress laughter. It is infectious. Jimmy Fallon’s SNL career, his greatest moments, are almost exclusively built around his difficulty in playing a straight man. The other players crack up as well. The sketch finds that magical balance between good comedic writing and the stage energy on the verge of chaos. The sketch is on the verge of collapse at every moment.

Which brings us to Christopher Walken, the essential component of the sketch as written and as performed. Students generally assert, without qualification, that Walken is the only actor that fit for that roll. His off-stage quirkiness carries into the performance itself in the minds of viewers. In short, “the Bruce Dickinson” is funny because Christopher Walken is weird, baby.

American humor at its best is alive and always feeding on the moment. That does not mean it must always be “live,” so to speak. Rather, it means that the humor must always derive from the energy between performer and audience and a mutual love and disdain for the world they share.

As “More Cowbell” has become more entrenched as a “classic” SNL sketch, it has become funnier still. For many of us, it also carries the warm glow of nostalgia for those times before we started rolling up our pants and counting our coffee spoons, when we could still stay awake late enough to see SNL and could recognize the hosts and the musical guests, and when those guests played musical instruments, and sometimes cowbells.

Heteroglossia and Dialect Humor: Buck Fanshaw’s Funeral

Jan McIntire-Strasburg, Executive Director–American Humor Studies Asociation

Humorist employ many different stylistic techniques in order to incite thought-provoking laughter in their readers. Once such is Mikhail Bahktin’s concept of heteroglossia. As Bahktin used it, this term refers to a linguistic play of different forms of a language from different races, classes or genders that highlights difference. While such use does not always result in humor, it is an excellent way to do so. Juxtaposing the dialects representing upper and lower classes, for example, can result in humorous misunderstandings that highlight the differences between the two classes in education or experience, and demonstrate the difficulties of effective communication between the two. The elements of contradiction and surprise that result from such conversations often invoke laughter.

Mark Twain makes excellent use of this linguistic play in “Buck Fanshaw’s Funeral,” a short sketch in his travel book, Roughing It. Miner Scotty Briggs’ Washoe slang and poker analogies are incomprehensible to the Eastern minister he is trying to convince to officiate at Buck’s funeral. The minister, in his attempts to understand Briggs’ request are equally confusing to the miner. The minister’s “clarifications” are long-winded and employ theological vocabulary well outside of Scotty’s experience. Thus for the space of several pages, the reader is treated to the experience of watching (hearing) two men groping toward an understanding of each other. Since the reader already knows what is required, she is free to enjoy laughter at the expense of both the formal, highly educated minister and the slangy Western miner.

Such laughter can, and often does, result in humor for entertainment purposes only. But in Twain’s case, the laughter engendered by Scotty and the minister also highlights major differences in Eastern and Western life in nineteenth century and the clash of two cultures within American borders. He demonstrates through the dialog a wide gulf in value systems and invites the reader to take a side—should we favor the minister who, though well educated, comes off as stuffy and superior, or should we instead value Scotty’s more homey and practical view of life on the frontier?

These insights are all available to us as we read Twain’s sketch, and because regional dialects comprised a large part of nineteenth century writing, Twain’s contemporaneous readers would have had no trouble discerning the meaning or recognizing the humor. However, contemporary readers, unused to the idiosyncratic spellings and pronunciations often find this kind of reading slow going, and the “translation” that must take place can affect how readers interpret the humor of the sketch. The sound recording below, because it offers the opportunity to hear rather than see the dialect, allows for a 21st century “reader” to avoid the difficulties of reading through the dialect, and lets the humor come through. Thus it frees the reader to think about what is said instead of spending time deciphering the text itself. For students who are inexperienced readers of dialect, this freedom is necessary to understanding. For experienced readers of Twain and dialect, hearing the text enhances the fun of it.

Sound recordings can make excellent teaching tools to demonstrate the concept of heteroglossia by showing them how it works in practice instead of telling them how it works. This recording of “Buck Fanshaw’s Funeral” is one example of how we can use sound to enhance teaching humor to undergraduates. It is also a great way for Twainiacs and humor scholars to entertain themselves.

See also an audio recording of the piece from Harry E. Humphrey in 1913.

The American Humor Studies Association welcomes teaching resources for their website. Please contact us at wustert@gmail.com

Editor’s Chair: Catching up with the American Humor Studies Association

Tracy Wuster, Vice President–American Humor Studies Association

The American Humor Studies Association has been active this past year working to promote humor studies as an academic field, and we are excited to share our work with you. Last year, we sponsored excellent panels at MLA and ALA. Many of our members presented on humor and Mark Twain at the 7th International Conference on the State of Mark Twain Studies, which featured an excellent keynote speech by Peter Kaminsky on the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor. We also published two issues of Studies in American Humor in the last year, as well as our newsletter, “To Wit.” This year sees the transition from Ed Piacentino to Judith Yaross Lee as editor of the journal, with myself as book review editor. Look for an interview with Judith on “Humor in America” soon and an excerpt from her wonderful new book, Twain’s Brand.

The AHSA is excited for our upcoming work for the next year:

*First, the AHSA is very excited to announce the creation of the “Jack Rosenbalm Prize for American Humor.” Jack was the first managing editor, and then editor, of Studies in American Humor and a strong promoter of humor studies as a field. He was awarded the Charlie Award in 1993.

Awarded tor the best article on American humor by a pre-tenure scholar, graduate student, adjunct professor, or independent scholar published in (or accepted for publication in) a peer-reviewed academic journal. Articles published in 2013 are eligible for the inaugural award. Please submit by 12/15/2013 to: ahsahumor@gmail.com

See link above for more information.

*The AHSA is working on Calls for Papers for three conferences next year–ALA, MLA, and our Quadrennial conference, which will be in New Orleans in December 2014. Look for the CFP for that and for MLA soon. The ALA call is looking for abstracts in the following topics:

1. “Political Humor from Franklin to Colbert”

2. “Teaching American Humor” (A Roundtable)

3. “Graphic Humor in American Periodicals” (Co-Sponsored with the Research Society for American Periodicals)

See our announcements page for more information.

*The AHSA is also co-sponsoring a Works in Progress symposium with the Mark Twain Circle of America in February. This working conference is intended to advance publication of work on American Humor, Mark Twain, and related work in progress. Individuals papers and group symposia will be offered relating to work in progress which will be presented by participants and discussed and developed with the help of attending scholars.

Where: The Red Lion Inn, Stockbridge, Massachusetts (http://www.redlioninn.com/)

When: Thursday-Saturday February 20-22

Information at the announcements page above.

* Call for Papers: MAD Magazine and Its Legacies Special issue of Studies in American Humor, Fall 2014

Since 1952, MAD Magazine has regaled humor lovers and inspired humor producers in many media. Studies in American Humor, the journal of the American Humor Studies Association, invites submission of scholarly papers devoted to MAD Magazine and its legacies for a special issue of the journal appearing in the fall of 2014, coedited by John Bird (Winthrop University) and Judith Yaross Lee (Ohio University).

Topics might include, but are not limited to: *humor, verbal and/or visual *subversive humor *satire (as technique, analysis of individual examples or themes, etc.) *parody (as technique, analysis of individual examples or themes, etc.) *individual artists and writers *regular and occasional features *one or mode recurrent themes (politics, technology, parenthood, suburbia) *cultural impact and legacies *influence, general and specific (including direct influence on individuals and genres) *reception

Potential contributors should send queries and abstracts (500-750 words) by October 1, 2013 or complete manuscripts by June 1, 2014. Email queries and abstracts to studiesinamericanhumor@ohio.edu. General information on Studies in American Humor and submission guidelines are available athttp://studiesinamericanhumor.org/.

*You can join the American Humor Studies Association by mail or electronically. Information on joining can be found on our website. The AHSA website contains a section for syllabus, assignments, and information on teaching American humor. We welcome any additions to this resources. “Humor in America” will be running a piece on using podcasts to teach dialect humor, prepared by our Executive Director–Jan McIntire Strasburg–in the next few weeks. Please contact me–Tracy Wuster (wustert@gmail.com)–if you have humor pedagogy resources you would like to share.

*Finally, the AHSA is excited to announce that Studies in American Humor will soon be included in JStor in its full run from 1976 through our recent issues. JSTor is kindly scanning past issues and hopes to include the journal in its next update. Keep an eye out.

Editor’s Chair: Humor Studies News for summer…

Tracy Wuster

ABE’s post from earlier this week highlighted the institution of the “editor’s chair,” which I have taken a seat in several times before to inform you, my dear readers, of the goings on for Humor in America and in humor studies more generally. Often, these postings have been inspired by the truest of all journalistic motives–a missed deadline.

So it goes.

I have also often written posts about milestones with the site. This morning, we passed 130,000 views. Our overall readership has been a steady 150 views or so for several months, following a summer and fall of larger readership. I have a theory that our current readership reflects a more accurate count of our reach, following the inflated numbers that followed Ricky Gervais tweeting our post and the traffic from an aggregator that referred hundreds a day during the fall and then fell out of love with us. I thank you for reading us.

On to the news:

* Steve Brykman and Phil Scepanski commented on this news story on humor in times of tragedy, specifically in the wake of the Boston Marathon bombing.

* There is a new issue of Studies in American Humor that members of the American Humor Studies Association recently received in the mail. The issue is a special issue on Kurt Vonnegut edited by Peter Kunze and Robert Tally. You can get the journal by joining the AHSA, as well as on some versions of EBSCO.

*Speaking of Studies in American Humor, I am the book review editor of the journal. I am currently looking for reviewers for 4-5 books. See here. The reviews would be for the Spring issue and due in the fall. If you know of a book that we might want to review, please let me know (wustert@gmail.com).

Up for review

*Also arriving in the mail is the newest issue of To Wit, the newsletter of the AHSA. The issue features a version of one of Jeffrey Melton’s pieces from Humor in America. Also in the newsletter is the listing of AHSA, Mark Twain Circle, and Kurt Vonnegut Society panels at ALA in Boston (May 23-26). Hope to see you there.

Up for review, too.

* The summer also features the 7th International Conference on the State of Mark Twain Studies (what I call “Mark Twain Summer Camp“) in Elmira, New York. Four of the editors of this site will be there.

Me, too!

*The 2013 ISHS Conference will be held from July 2 to July 6, 2013 on the campus of the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, USA.

Yes, up for review!

*We have a twitter account where we post articles on humor, links, etc. Al Franken, Baratunde Thurston, David Brent, and Walt Whitman are followers… maybe you should, too.

*Please let me know if you have any news, CFPs, etc. on humor studies. Thanks.

In the Archives: “Yankeeana” from the London and Westminster Review (1838)

Tracy Wuster

Much of the writing on the subject of “American humor” in the nineteenth century–when the idea of a distinctly American humor took shape–came from British critics writing in British journals on the subject of “American Humour.”

Whereas American literature, philosophy, and theology had largely been imitative of European models, British critics consistently saw American “humour” as a new development in American national literature. American humor was increasingly framed as a worthwhile expression of American national life, in addition to being a product that the British reading public consumed with increasing eagerness. American humor expressed important aspects of American life: the scale and grandness of the land through exaggeration, the democratic variety of people through its diversity, and the immaturity of the country and its people through its exuberance and occasional profanity. To use a popular critical metaphor, the British saw humor as a national growth of a young nation, the first literary fruits of the national soil.

One of the first major critical assessments of American Humour can be found in John Robertson’s “Yankeeana” from The Westminster Review of December 1838 (reprinted in The Museum of Foreign Literature, Science, and Art, Vol. VII, January to April 1839 in Philadelphia). Printed under the initials W.H., this piece examined the works of the following humorists:

This argument is based on the critical assumption that humor as a genre was national in expression, that “it is impregnated with the convictions, customs, and associations of a nation.” American humor expressed the conditions of the people, a list that included: institutions, laws, customs, characters, scenery, Democracy, forests, freedom, universal suffrage, bear-hunts, Puritans, the American revolution, and the “influence of the soil and the social manners of the time.” Such peculiar characteristics of a nation infuse themselves into men, who express the national character through their literature—starting with humor.

Although it takes the author awhile to get to his point, give it some time. Here is the text, in full:

These books show that American literature has ceased to be exclusively imitative. A few writers have appeared in the United States, who instead of being European and English in their styles of thought and diction, [these writers] are American—who, therefore, produce original sounds of far-off echoes,—fresh and vigorous pictures instead of comparatively idealess copies. A portion of American literature has become national and original, and, naturally enough, this portion of it is that which in all countries is always most national and original—because made more than any other by the collective mind of the nation—the humorous.

We have many things to say on national humour, very few of which we can say on the present occasion. But two or three words we must pass on the heresies which abound in the present state of critical opinion on the subject of national humour: we say critical, and not public, for, thank God, the former has very little to do with the latter.

“Lord Byron,”–says William Hazlitt, in a very agreeable and suggestive volume of ‘Sketches and Essays,’ now first collected by his son,–“was in the habit of railing at the spirit of our good old comedy, and of abusing Shakspeare’s Clowns and Fools, which he said, the refinement of the French and Italian stage would not endure, and which only our grossness and puerile taste could tolerate. In this I agree with him; and it is pat to my purpose. I flatter myself that we are almost the only people who understand and relish nonsense.” This is the excuse for the humour of Shakspeare, his rich and genuine English humour!

In Lord Byron the taste which the above opinion expresses is easily accounted for; it was the consequences of his having early formed himself according to the Pope and Gifford school, which was the dominant one among the Cambridge students of his time. Scottish highland scenery, and European travel, aided by the influences of the revival of a more vigorous and natural taste in the public, made his poems much better than the taste of the narrow school to which he belonged could ever have made them; but above the dicta of his school his critical judgment never rose. We thought the matter more inexplicable as regards William Hazlitt, a man superior to Byron in force and acuteness of understanding–until we found the following declaration of his views:–“In fact, I am very much of the opinion of that old Scotch gentleman who owned that ‘he preferred the dullest book he had ever read to the most brilliant conversation it had ever been his lot to hear.’ ” A man to whom the study of books was so much and the study of men so little as this, could not possibly understand the humour of Shakspeare’s Clowns and Fools, or national humour of any sort. The characters of a Trinculo, or Bardolph, a Quickley, or a Silence, are matters beyond him. That man was never born whose genuine talk, let it be as dull as it may, and whose character, if studied aright, is not pregnant with thoughts, deep and immortal thoughts, enough to fill many books. A man is a volume stored all over with thoughts and meanings, as deep and great as God. A book, even when it contains the “life’s blood of an immortal spirit,” still is not an immortal spirit, not a God-created form. Wofully fast will be his growth in ignorance who prefers reading books to reading men. But the time-honoured critical journals have critics–

“The earth hath bubbles as the waters hath”–

and William Hazlitt, with his eloquent vehemence, was one of the best of them.

The public have of late, by the appreciation of the genuine English humour of Mr. Dickens, shown that the days when the refinement which revises Shakspeare and ascribes the toleration of his humour to grossness and puerility of taste, or relish for nonsense, have long gone by. The next good sign is the appreciation of the humour of the Americans, in all its peculiar and unmitigated nationality. Humour is national when it is impregnated with the convictions, customs, and associations of a nation. What these, in the case of America, are, we thus indicated in a former number:–“The Americans are a democratic people; a people without poor; without rich; with a ‘far-west’ behind them; so situated as to be in no danger of aggression from without; sprung mostly from the Puritans; speaking the language of a foreign country; with no established church; with no endowment for the support of a learned class; with boundless facilities for “raising themselves in the world;” and where a large family is a fortune. They are English men who are all well off; who never were conquered; who never had feudalism on their soil; and who, instead of having the manners of society determined by a Royal court in all essential imitative to the present hour of that of Louis the Fourteenth of France had them formed, more or less, by the stern influences of Puritanism.

National American humour must be all this transformed into shapes which produce laughter. The humour of a people is their institutions, laws, customs, manners, habits, characters, convictions,—their scenery, whether of the sea, the city, or the hills,—expressed in the language of the ludicrous, uttering themselves in the tones of genuine and heartfelt mirth. Democracy and the ‘far-west’ made Colonel Crockett: he is a product of forests, freedom, universal suffrage, and bear-hunts. The Puritans and the American revolution, joined to the influence of the soil and the social manners of the time, have all contributed to the production of the character of Sam Slick. The institutions and scenery, the convictions and the habits of a people, become enwrought into their thoughts, and of course their merry, as well as their serious thoughts. In America, at present, accidents of steamboats are extremely common, and have therefore a place in the mind of every American. Hence we are told that, when asked whether he was seriously injured by the explosion of the boiler of the St. Leonard steamer, Major N. replied that he was so used to be blown-up by his wife, that a mere steamer had no effect upon him. In another instance laughter is produced out of the very cataracts which form so noble a feature in American scenery. The captain of a Kentucky steam-boat praises his vessel thus:—”She trots off like a horse—all boiler—full pressure—it’s hard work to hold her in at the wharfs and landings. I could run her up a cataract. She draws eight inches of water—goes at three knots a minute—and jumps all the snags and sand-banks.” The Falls of Niagara themselves become redolent with humour. “Sam Patch was a great diver, and the last dive he took was off the Falls of Niagara, and he was never heard of agin till t’other day, when Captain Enoch Wentworth, of the Susy Ann whaler, saw him in the South Sea. ‘Why,’ says Captain Enoch to him—’why, Sam,’ says he, ‘how on airth did you get here, I thought you was drowned at the Canadian lines.’—’Why,’ says Sam, ‘I didn’t get on earth here at all, but I came slap through it. In that are Niagara dive I went so everlasting deep, I thought it was just as short to come up t’other side, so out I came on these parts. If I don’t take the shine off the sea-serpent, when I get back to Boston, then my name’s not Sam Patch.'”

The curiosity of the public regarding the peculiar nature of American humour, seems to have been very easily satisfied with the application of the all-sufficing word exaggeration. We have, in a former number, (‘London and Westminster Review’ for January 1838, p. 266.) sufficiently disposed of exaggeration, as an explanation of the ludicrous. Extravagance is a characteristic of American humour, though very far from being a peculiarity of it; and, when a New York paper, speaking of hot weather, says:—”We must go somewhere—we are dissolving daily—so are our neighbours.—It was rumoured yesterday, that three large ridges of fat, found on the side-walk in Wall street, were caused by Thad. Phelps, Harry Ward, and Tom Van Pine, passing that way a short time before:—the humour does not consist in the exaggeration that the heat is actually dissolving people daily—a common-place at which no one would laugh—but in the representation of these respectable citizens as producing ridges of fat. It is humour, and not wit, on account of the infusion of character and locality into it. The man who put his umbrella into bed and himself stood up in the corner, and the man who was so tall that he required to go up a ladder to shave himself, with all their brethren, are not humorous and ludicrous because their peculiarities are exaggerated, but because the umbrella and the man change places, and because a man by reason of his tallness is supposed too short to reach himself.

The cause of laughter is the ascription to objects of qualities or the representations of objects or persons with qualities the opposite of their own:—Humour is this ascription or representation when impregnated with character, whether individual or national.

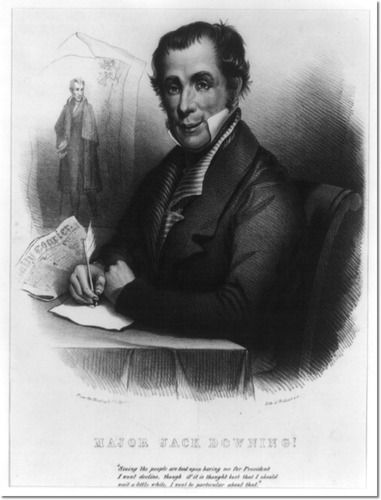

It is not at all needful that we should illustrate at length by extracts the general remarks we have made, since the extensive circulation and notice which American humour has of late obtained in England have impressed its general features on almost all minds. But we may recall them more vividly to the reader, and connect them more evidently with the causes in which they originate, by showing very briefly how institutions infuse themselves into men, how the peculiarities of the nation re-appear in the individual, and how, in short, the elements of the society of the United States are ludicrously combined and modified in the characters, real and fictitious, of Sam Slick, Colonel Crockett, and Major Jack Downing.

Sam Slick is described as “a tall thin man, with hollow cheeks and bright twinkling black eyes, mounted on a good bay horse, something out of condition. He had a dialect too rich to be mistaken as genuine Yankee.” His clothes were well made and of good materials, but looked as if their owner had shrunk since they were made for him. A large brooch and some superfluous seals and gold keys, which ornamented his outward man, looked “New England” like. “A visit to the States had, perhaps, I thought” —says the traveller, who describes him, as he fell in with him on the road—”turned this Colchester beau into a Yankee fop.” The traveller at one time thought him a lawyer, at another a Methodist preacher, but on the whole was very much puzzled what to make of him. Sam Slick turns out to be an exceedingly shrewd and amusing fellow, who swims prosperously through the world by means of “soft sawder” and “human natur.” Ho is a go-ahead man, convinced that the Slicks are the best of Yankees, the Yankees the best of the Americans, and the Americans are generally allowed to be the finest people in the world. He is an enthusiast in railroads. Of the “gals” of Rhode Island he says they, beat the Eyetalians by a long chalk—they sing so high some on ’em they go clear out o’ hearin, like a lark. When a man gets married, he says, his wife “larns him how vinegar is made—Put plenty of sugar into the water aforehand, my dear, says she, if you want to make it real sharp.” The reader will recognise several of the peculiarities of American society in “Setting up for Governor:”—

” ‘I never see one of them queer little old-fashioned teapots, like that are in the cupboard of Marm Pngwash,’ said the Clockmaker, ‘that I don’t think of Lawyer Crowningshield and his wife. When I was down to Rhode Island last, I spent an evening with them. After I had been there a while, the black househelp brought in a little home-made dipt candle, stuck in a turnip sliced in two, to make it stand straight, and set it down on the table.’—’Why,’ says the Lawyer to his wife, ‘Increase, my dear, what on earth is the meaning o’ that? What does little Viney mean by bringin in such a light as this, that aint ftt for even a log hut of one of our free and enlightened citizens away down east; where’s the lamp?’—’My dear,’ says she, ‘I ordered it—you know they are a goin to set you up for Governor next year, and I allot we must economise or we will be ruined—the salary is only four hundred dollars a year, you know, and you’ll have to give up your practice—we cah’t afford nothin now.’

“Well, when tea was brought in, there was a little wee china teapot, that held about the matter of half a pint or so, and cups and sarcers about the bigness of children’s toys. When he seed that, he grew most peskily ryled, his under lip curled down like a peach leaf that’s got a worm in it, and he stripped his teeth, and showed his grinders like a bull-dog. ‘What foolery is this?’ said he.—’My dear,’ said she, ‘it’s the foolery of being Governor; if you choose to sacrifice all your comfort to being the first rung in the ladder, don’t blame me for it. I didn’t nominate you—I had not art nor part in it. It was cooked up at that are Convention, at Town Hall.’ Well, he sot for some time without sayin a word, lookin as black as a thunder cloud, just ready to make all natur crack agin. At last he gets up, and walks round behind his wife’s chair, and takin her face between his two hands, he turns it up and gives her a buss that went off like a pistol—it fairly made my mouth water to see him; thinks I, them lips aint a bad bank to deposit one’s spare kisses in, neither. ‘Increase, my dear,’ said he, ‘I believe you are half right, I’ll decline to-morrow, I’ll have nothin to do with it—I won’t be a Governor on no account.

“Well, she had to haw and gee like, both a little, afore she could get her head out of his hands; and then she said, ‘Zachariah,’ says she, ‘how you do act, aint you ashamed? Do for gracious sake behave yourself:’ and she coloured up all over like a crimson piany; ‘if you havn’t foozled all my hair, too, that’s a fact,’ says she; and she put her curls to rights, and looked as pleased as fun, though poutin all the time, and walked right out of the room. Presently in come two well-dressed house-helps, one with a splendid gilt lamp, a real London touch, and another with a tea tray, with a large solid silver coffee-pot, and tea-pot, and a cream jug, and sugar bowl, of the same genuine metal, and a most an elegant set of real gilt china. Then in came Marm Crowingshield herself, lookin as proud as if she would not call the President her cousin; and she gave the Lawer a look, as much as to say, I guess when Mr. Slick is gone I’ll pay you off that are kiss with interest, you dear you—I’ll answer a bill at sight for it, I will, you may depend.

“‘I believe,’ said he, ‘agin, you are right, Increase, my dear, its an expensive kind of honour that bein Governor, and no great thanks neither; great cry and little wool, all talk and no cider—its enough I guess for a man to govern his own family, aint it, dear?'”

Of Colonel Crockett we shall not say one word further than to direct the attention of our readers to a passage which they may have seen before, but which they will not regret seeing again, so full is it of meanings regarding both the man and the influences by which he was made what he was. The humours of an English election are somewhat different from those described by Crockett, and he evidently knows little of anything like the loyal affection which the electors of the mother country have for “her Majesty’s likeness in gold.”

“I met with three candidates for the Legislature; a Doctor Butler, who was, by marriage, a nephew to General Jackson, a Major Lynn, and a Mr. McEver, all first-rate men. We all took a horn together, and some person present said to me, ‘Crockett, you must offer for the Legislature.’ I told him I lived at least forty miles from any white settlement, and had no thought of becoming a candidate at that time. So we all parted, and I and my little boy went on home.

“It was about a week or two after this, that a man came to my house, and told me I was a candidate. I told him not so. But he took out a newspaper from his pocket, and show’d me where I was announced. I said to my wife that this was all a burlesque on me, but I was determined to make it cost the man who had put it there at least the value of the printing, and of the fun he wanted at my expense. So I hired a young man to work in my place on my farm, and turned out myself electioneering. I hadn’t been out long before I found the people began to talk very much about the bearhunter, the man from the cane; and the three gentlemen, who I have already named, soon found it necassary to enter into an agreement to have a sort of caucus at their March court, to determine which of them was the strongest, and the other two was to withdraw and support him. As the court came on, each one of them spread himself, to secure the nomination; but it fell on Dr. Butler, and the rest backed out. The doctor was a clever fellow, and I have often said he was the most talented man I ever run against for any office. His being related to Gen’l. Jackson also helped him on very much; but I was in for it, and I was determined to push ahead and go through, or stick. Their meeting was held in Madison county, which was the strongest in the representative district, which was composed of eleven counties, and they seemed bent on having the member from there.

“At this time Colonel Alexander was a candidate for Congress, and attending one of his public meetings one day, I walked to where he was treating the people, and he gave me an introduction to several of his acquaintances, and informed them that I was out electioneering. In a little time my competitor, Doctor Butler, came along; he passed me without noticing me, and I suppose, indeed, he did not recognise me. But I hailed him, as I was for all sorts of fun; and when he turned to me, I said to him, ‘Well, doctor, I suppose they have weighed you out to me; but I should ltke to know why they fixed your election for March instead of August? This is,’ said I, ‘a branfire new way of doing business, if a caucus is to make a representative for the people!’ He then discovered who I was, and cried out ‘D—n it, Crockett, is that you?’—’Be sure it is,’ said I, ‘but I don’t want it understood that I have come electioneering. I have just crept out of the cane, to see what discoveries I could make among the white folks.’ I told him that when I set out electioneering I would go prepared to put every man on as good footing when I left him as I found him on. I would, theretore, have me a large buckskin hunting-shirt made, with a couple of pockets holding about a peck each; and that in one I would carry a great big twist of tobacco, and in the other my bottle of liquor; for I knowed when I met a man and offered him a dram, he would throw out the quid of tobacco to take one, and after he had taken his horn, I would out with my twist, and give him another chaw. And in this way he would not be worse off than when I found him; and I would be sure to leave him in a first-rate good-humour. He said I could beat him electioneering all hollow. I told him I would give him better evidence of that before August, notwithstanding he had many advantages over me, and particularly in the way of money; but I told him that I would go on the products of the country; that I had industrious children, and the best of coon dogs, and they would hunt overy night till midnight to support my election; and when the coon fur wa’n’t good I would myself go a wolfing, and shoot down a wolf, and skin his head, and his scalp would be good to me for three dollars, in our state treasury money; and in this way I would get along on the big string. He stood like he was both amused and astonished, and the whole crowd was in a roar of laughter. From this place I returned home, leaving the people in a first-rate way; and I was sure I would do a good business among them. At any rate I was determined to stand up to my lick-log, salt or no salt.

“In a short time there came out two other candidates, a Mr. Shaw and a Mr. Brown. We all ran the race through; and when the election was over, it turned out that I beat them all by a majority of two hundred and forty-seven votes, and was again returned as a member of the Legislature from a new region of the country, without losing a session. This reminded me of the old saying—’A fool for luck, and a poor man for children.'”

Major Jack Downing is, like Sam Slick, a fictitious character, while Crockett, though now dead, was a real one. But in the letters of Major Jack Downing, there is reality enough to show that they express much that is highly characteristic of America. Here is a caricature of some of the toils of a President.

“I cant stop to tell you in this letter how we got along to Philadelphy, though we had a pretty easy time some of the way in the steam-boats. And I cant stop to tell you of half the fine things I have seen here. They took us up into a great hall this morning as big as a meeting-house, and then the folks begun to pour in by thousands to shake hands with the President; federalists and all, it made no difference. There was such a stream of ’em coming in that the hall was full in a few minutes, and it was so jammed up round the door that they could’nt get out again if they were to die. So they had to knock out some of the windows and go out t’other way.

“The President shook hands with all his might an hour or two, till he got so tired he could’nt hardly stand it. I took hold and shook for him once in awhile to help him along, but at last he got so tired he had to lay down on a soft bench covered with cloth and shake as well as he could, and when he could’nt shake he’d nod to ’em as they come along. And at last he got so beat out, he couldn’t only wrinkle his forard and wink. Then I kind of stood behind him and reached my arm oand under his, and shook for him for about a half an hour as tight as I could spring. Then we concluded it was best to adjourn for to-day.”

In the following passage, with which we conclude, there is some playful banter on the present President of the United States.

“But you see the trouble ont was, there was some difficulty between I and Mr. Van Buren. Some how or other Mr. Van Buren always looked kind of jealous at me all the time after he met us at New York; and I couldn’t help minding every time the folks hollered ‘hoorah for Major Downing’ he would turn as red as a blaze of fire. And wherever he stopped to take a bite or to have a chat, he would always work it, if he could, somehow or other so as to crowd in between me and the President. Well, ye see, I wouldn’t mind much about it, but would jest step round ‘tother side. And though I say it myself, the folks would look at me, let me be on which side I would; and after they’d cried hoorah for the President, they’d most always sing out ‘hoorah for Major Downing.’ Mr. Van Buren kept growing more and more fidgety till we got to Concord. And there we had a room full of sturdy old democrats of New Hampshire, and after they all had flocked round the old President and shook hands with him, he happened to introduce me to some of ’em before he did Mr. Van Buren. At that the fat was all in the fire. Mr. Van Buren wheeled about and marched out of the room looking as though he could bite a board nail off. The President had to send for him three times before he could get him back into the room again. And when he did come, he didn’t speak to me for the whole evening. However we kept it from the company pretty much; but when we come to go up to bed that night, wo had a real quarrel. It was nothing but jaw, jaw, the whole night. Mr. Woodbury and Mr. Cass tried to pacify us all they could, but it was all in vain, we didn’t one of us get a wink of sleep, and shouldn’t if the night had lasted a fortnight. Mr. Van Buren said the President had dishonoured the country by placing a military Major on half-pay before the second officer of the government. The President begged him to consider that I was a very particular friend of his; that I had been a great help to him at both ends of the country; that I had kept the British out of Madawaska away down in Maine, and had marched my company clear from Downingville to Washington, on my way to South Carolina, to put down the nullifiers; and he thought I was entitled to as much respect as any man in the country.

“This nettled Mr. Van Buren peskily.—He said he thought it was a fine time of day if a raw jockey from an obscure village away down east, jest because he had a Major’s commission, was going to throw the Vice President of the United States and the heads of Departments into the back ground. At this my dander began to rise, and I stepped right up to him, and says I, Mr. Van Buren, you are the last man that ought to call me a jockey. And if you’ll go to Downingville and stand up before my company with Sargeant Joel at their head, and call Downingville an obscure village, I’ll let you use my head for a foot-hall as long as you live afterwards. For if they wouldn’t blow you into ten thousand atoms, I’ll never guess again. We got so high at last that the old President hopt off the bed like a boy; for he had laid down to rest him, bein it was near daylight though he couldn’t get to sleep.”

H.W.

[1] John Robertson, “Yankeeana.” The Westminster Review (December 1838). Quoted in The Museum of Foreign Literature, Science, and Art, vol. VII—New Series (Philadelphia: E. Littell & Co., 1839), 75-6.

Editor’s Chair: Let’s Destroy the Sun

Tracy Wuster

A friend of mine–and one of my favorite pessimists–has said that she cures writer’s block by placing one simple sentence at the top of her page and going from there. So here goes:

Since the dawn of time, man has yearned to destroy the sun.

There. Maybe that will help…

Nope. I just don’t have anything intelligent to say about humor right now, nothing like Jeffrey Melton’s sharp piece on pedagogy of humor, or Matt Powell’s excellent work on Andy Kaufman’s music, Matthew Duabe’s insightful piece on performance and Princess Ivona, Sharon McCoy’s truly funny meditation on germs in public places, Caroline Zarlengo Sposto’s birthday wishes to that great American poet Muhammed Ali, Phil Scepanski’s insightful discussion of sick humor, or ABE’s solid writing on Marc Maron’s podcast. See, I have resorted to a clip show, the final resort of the lazy sitcom writer (although those are all excellent pieces worth reading, for sure).

But I have nothing. I wish I could turn my external circumstances–which are not really conducive to writing about humor–into humorous insight, as Sharon McCoy has so wonderfully done on our pages. But I can’t. I apologize.

Instead, I will point to the work I have been doing with the AHSA and Humor Studies Caucus of the ASA to plan panels for upcoming conferences in Boston (ALA) and D.C. (ASA). Also, check out the announcements page above or on the AHSA website for new CFPs for the AHSA at MLA 2014, humor studies and Mark Twain at the RMLA, and humor studies at SAMLA.

Also, I blame my book, the manuscript of which is due to the University of Missouri Press at the end of the month. Here is a brief sample, touching on Twain and humor:

In 1874, as Twain was writing the series “Old Times on the Mississippi” for the Atlantic, Howells attempted to ease Twain’s fears about the audience he was writing for, stating in a letter “Don’t write at any supposed Atlantic audience, but yarn it off as into my sympathetic ear.” Twain responded with a line that reflects a sense of relief at this new professional opportunity: “It isn’t the Atlantic audience that distresses me; for it is the only audience that I sit down before in perfect serenity (for the simple reason that it don’t require a ‘humorist’ to paint himself stripèd & stand on his head every fifteen minutes.)”[1] The possibility of earning a living, or at least a reputation, as a new type of humorist—one who didn’t have to curry public favor with constant buffoonery—seems to have appealed to Twain.

[1] William D. Howells to SLC, 3 December 1874, (UCLC 32073).http://www.marktwainproject.org/x tf/view?docId=letters/UCLC32073.xml;styl e=letter;brand=mtp and SLC to William Dean Howells, 8 Dec 1874, Hartford, Conn. (UCCL 05257). <http://www.marktwainproject.org/xtf/view?docId=letters/UCCL05257.xml;style=letter;brand=mtp>

Editor’s Chair: Busy month for humor studies

Tracy Wuster

Hello dear readers. We at “Humor in America” hope you had jolly holidays and festive new year’s and such. Last year, we said goodbye to a great group of editors–Bonnie Applebeet, Joe Faina, Beza Merid, and David Olsen. We also added Jeffrey Melton, Matt Powell, ABE, Matthew Daube, Phil Scepanski, and saw the return of Sharon McCoy and Steve Brykman. And don’t forget the wonderful contributions of Caroline Sposto. A big thank you to all the editors and contributors from the past year. If you would like to contribute a post, please let me know.

The month of January brings a whole slew of humor studies opportunities to think about.

**American Humor Studies Association at ALA:

Abstracts due January 15. Conference is May 23-6 in Boston.

Abstracts due January 15. Conference is May 23-6 in Boston.

1. “Humor in Periodicals: From Punch to Mad”—Abstracts (300 words max.) are encouraged on the role of humorous literature in American periodicals from the early national period to the present. Subject adaptable to both humorous periodicals and humor in serious periodicals across a wide time range; thus, title will change to reflect composition of panel.

2. “Reading Humorous Texts”–Abstracts (300 words max.) are encouraged on the interpretation, recovery, or pedagogy of humorous texts from novels and poems to plays and stand-up. Some focus on the act of interpretation of humor in its historical, performative, formal, or other cultural context is encouraged.

Please e-mail abstracts no later than January 15, 2013 to Tracy Wuster (wustert@gmail.com) with the subject line: “AHSA session, 2013 ALA.” Notifications will go out no later than January 20, 2013.

**Humor Studies Caucus at the American Studies Association.

Abstracts due January 15

Deadline extended!.

American Studies Association Annual Meeting:

“Beyond the Logic of Debt, Toward an Ethics of Collective Dissent,”

November 21-24, 2013: Hilton Washington, DC

http://www.theasa.net/annual_meeting/page/submit_a_proposal/

Proposals on any aspect of American Humor will be welcome. Panels will be assembled for submission by the January 26 deadline.

Proposals should be no more than 500 words and should include a brief CV (1 page). Please include current ASA membership status.

Proposals (and questions) should be sent to Tracy Wuster and Jennifer Hughes: wustert@gmail.com & jahughes@yhc.edu

**Looking for book reviewers for Studies in American Humor.

We have a number of books for which we need reviewers for our Fall 2013 issue.

Here are the books looking for reviewers:

1. Avashi, Bernard. Promiscuous: “Portnoy’s Complaint” and Our Doomed Pursuit of Happiness New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012.

2. Ferrari, Chiara Francesca. Since When is Fran Drescher Jewish?: Dubbing Stereotypes in The Nanny, The Simpsons, and The Sopranos. Foreword by Joseph Straubhaar. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010.

3. Holtz, Allan. American Newspaper Comics: An Encyclopedic Reference Guide. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2012.

4. Kohen, Yael. We Killed: The Rise of Women in American Comedy. New York: Sarah Crichton Books, 2012

5. Nel, Phil, Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss: How an Unlikely Couple Found Love, Dodged the FBI, and Transformed Children’s Literature. University Press of Mississippi, 2012. 368 pages, 88 illustrations.

6. Morris, Roy Jr. Declaring His Genius: Oscar Wilde in North America Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013.

We especially encourage graduate students and junior scholars to review books. If you are interested in reviewing one of the above books, please contact Tracy Wuster (wustert@gmail.com) with the information below, as well as the specific book you are interested in reviewing:

In the Archives: Thomas Nast and Santa Claus (1862-1890)

I can remember my first scholarly thought. Well, I should say that I can visualize the context of my first scholarly thought. Like a Polaroid of a younger me looking through a View-Master: I know that I saw something, and how, but can’t remember what.

I can almost replicate the place from memory, but will never replicate the time. Heraclitus, who was smarter than the average Greek, once wrote fragmentedly, “You cannot step into the same river, for other waters and yet others go ever flowing on.” True, but the Greeks widely preached the maxim to “Know Thyself,” and I remember helping my grandfather once, and being rewarded with a copy of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

To be precise it was The Annotated Huckleberry Finn, edited by Michael Patrick Hearn, copyright 1981 by Clarkson N. Potter, republished by Norton & Company. When my grandfather gave me the book it was still new scholarship, and I was no scholar, but the text fascinated me. Densely illustrated, the Potter edition uses marginalia to communicate the context of both the novel and Hearn’s Introduction like an analogue prototype for the internet. I was a babe in the woods, looking through the first book I ever owned that did not involve talking animals or a young sleuth by the name of Encyclopedia Brown. I was proud that someone thought me ready for such an impressive text, but make no mistake, the pictures helped. As a child I was not a strong reader, but I was wildly artistic. And the first page I opened had a caricature of two men, in nightgowns, with nineteenth-century facial hair, collecting clocks.

I don’t think I can reproduce it here for legal purposes, but Roman numeral lvi (56) of the Norton edition will show you the two figures identified as the authors George W. Cable and Mark Twain, drawn by Thomas Nast, on Thanksgiving, 1884.

There was no other description behind the cause of their act, collecting clocks at five before midnight, besides: “The two spent Thanksgiving at Thomas Nast’s home in Morristown, New Jersey.” I cannot fault Hearn’s lack of insight, because it sparked the first real academic inquiry in my young mind: What the hell is going on?

I can tell you that later I learned:

On Thanksgiving Eve the readers were in Morristown, New Jersey, where they were entertained by Thomas Nast. The cartoonist prepared a quiet supper for them and they remained overnight in the Nast home. They were to leave next morning by an early train, and Mrs. Nast had agreed to see that they were up in due season. When she woke next morning there seemed a strange silence in the house and she grew suspicious. Going to the servants’ room, she found them sleeping soundly. The alarm-clock in the back hall had stopped at about the hour the guests retired. The studio clock was also found stopped; in fact, every timepiece on the premises had retired from business. Clemens had found that the clocks interfered with his getting to sleep, and he had quieted them regardless of early trains and reading engagements. On being accused of duplicity he said: “Well, those clocks were all overworked, anyway. They will feel much better for a night’s rest.” A few days later Nast sent him a caricature drawing—a picture which showed Mark Twain getting rid of the offending clocks. (Mark Twain, a Biography, vol. II, part 1, 188)

But all this postdates my first academic thought. Before I knew Huck, Jim, the Mississippi River, or the author who sent them down it. I saw a picture and knew the name of the man who drew it. Thomas Nast. I remember I wanted to know more, and now I can share some of it with you, in context.

Editor’s Chair: 100k Views

Tracy Wuster, Founding Editor

From time to time, I have seen fit to print reports on the general progress of this website as a publishing venture. As the editor, I feel it is my prerogative, stretching back to the great tradition of 19th century magazine editors to speak my mind and address our readers—both real and imagined. Also in the tradition of those editors, I have not been able to resist the urge to explain what I think we are up to with our publication and to, in addition, engage in that greatest of all editorial goals—filling space.

From time to time, I have seen fit to print reports on the general progress of this website as a publishing venture. As the editor, I feel it is my prerogative, stretching back to the great tradition of 19th century magazine editors to speak my mind and address our readers—both real and imagined. Also in the tradition of those editors, I have not been able to resist the urge to explain what I think we are up to with our publication and to, in addition, engage in that greatest of all editorial goals—filling space.

Upon reaching one hundred thousand views, today December 2, 2012, I cannot resist expounding on some of the statistics that have accumulated for us to reach this milestone. I have no idea if this is a lot of views for a publication of this sort—although there are not a whole lot of publications of this sort for me to compare to. I will choose to treat it as a grand milestone, one worthy of reflection. Plus, I have long been obsessed with statistics and milestones, and the WordPress statistics page, which tallies the use of the site in real-time, has been a boon to my obsession.

Number of Contributors: 23

Number of Posts: 214

1st Post:

Appropos of a first post…

June 24, 2011

Total views: 5

1st Official Post (Public Launch):

Politics and the American Sense of Humor

by M. Thomas Inge

August 11, 2011

Total Views: 2405

Sunday Stand-Up: Temporary Retirement (+ Louis C.K.)

Tracy Wuster, Editor

For the time being, or maybe permanently (who knows?), we are retiring the “Stand-up Sunday” (or “Sunday Stand-Up”) feature. All Sunday posts, actually. We will be moving to a twice per week schedule, with posts on Monday and Thursday (with an occasional post at other times, if we feel like it, or have a lot of posts). We will still have discussions of stand-up, I am sure, and we welcome you to contribute (yes, you, you-who-are-reading-this).

As we approach 100k views, we are thankful for your visiting us, especially those of you who are regular readers (we hope you are out there). But we don’t know much about our readers, so please take a minute to fill out these polls:

Thank you for answering. We are very curious about you, our readers, and hope that we are presenting you with writing that you find worth reading and a site that is worth coming back to. We appreciate feedback on the design, content, and direction of the site.

And since this is the final Sunday Stand-Up post for awhile, at least, I will end with some stand-up.