An interview with Chris Gilbert, author of “Caricature and National Character: The United States at War”

Want to order the book? Here is a discount code: ZOOM40

Tell me about your start in humor studies. How and when did you begin pursuing it as a subject? who or what has influenced you as a scholar of humor?

In some ways, my “study” of humor began at a very early age. I like comics as a kid. I also really liked television cartoons—The Simpsons, of course, but also shows like Pinky and the Brain and The Ren & Stimpy Show when I was fairly young, and then South Park and Family Guy when I was in high school. And I was a huge fan of The Far Sidecomic strip and the magazines MAD and Cracked. You can most certainly see these influences on some of the things I have written about as an academic—MAD, for one example unrelated to my book, as well as the obvious: editorial cartoons. But these influences were there, too, in my interests as an undergrad and in my decision to more formally start studying the role of humor in public culture, for instance in the comic antics of Kurt Cobain. I wrote my undergraduate thesis on Cobain for a course in rhetorical criticism, and focused my attention on how he used humor in interviews and public appearances and concerts to disrupt his celebrity and throw wrenches in the spokes of the corporate system of music production and hero—never mind anti-hero—worship.

I also wrote about the humor behind Hunter S. Thompson’s so-called Gonzo journalism, in addition to the comic artworks of Thompson’s longtime collaborator, the British caricature artist and illustrator, Ralph Steadman. I should also note that I’ve always dabbled in pen-and-ink drawings myself. In grade school and then again in middle school, I was known as the kid who could draw. That reputation has stuck to this day, with both friends and family members asking me whether or not I drew the picture of Uncle Sam by Francis Gilbert Atwood for my book when they first saw the cover. All of this is to say that a deep immersion in various things that can be seen as comically artful and, by extension, humorous paved the way for the intellectual pursuits that have motivated me since I was a burgeoning academic.

Tell me about the genesis and creation of this project. What questions did you set out to answer, and how did your project develop to answer them?

The initial impetus for this project grew out of my fascination with the extent to which editorial cartoons have long served so many rhetorical purposes in U.S. American wartimes. Since the Founding Period, they have been used for propaganda, military recruitment, criticism, and so on. What I realized more and more, though, as I looked into editorial cartoons in specific moments of both armed conflict and political crisis (which, in our history, often go together) is that they are frequently at the center of images and ideas about cultural identity. Consider Ben Franklin’s early artwork that dabbled in depictions of something like national union in his appeal to join or die.

Consider Thomas Nast, an Irish immigrant, in the Civil War era making caricatures of Americanism with a nationalistic kind of liberalism that pushed him toward the heart of principles that we all like to say are part and parcel of who we are. Liberty. Freedom. Opportunity. And consider that Nast’s work over and again appealed to the better angels of civic virtue as they come up against the vices, and even the violent spasms and paroxysms, that emanate from our political differences, i.e., xenophobia, racism, sexism, and other forms of prejudice that undermine—or, sadly, underwrite—collective pride.

Then there’s the collection of editorial cartoons about American Empire at the turn of the twentieth century and their mockeries of our emerging war machine as an arsenal of democracy unto itself that swelled during the two world wars. I could go on with references to the Cold War and the post-9/11 milieu and the rhetorical mire of our present moment, making connections between notions that the might of militarism blends with the righteousness of presumed manifest destiny. Suffice it to say, though, that in this entire complex history is a certain comic spirit that imbues caricatures of American cultural identity, and thereby national character, from war posters through reflections on cultural warfare in comic illustrations to revilements of warism and its collateral damages in editorial cartoons. Quite simply, I wanted to know why, in addition to how this trajectory of wartime caricature lends a powerful and dynamic endurance to comicality in our national character.

.

Your book—Caricature and National Character—focuses on how political cartoons during times of war help us understand American character. Can you give us an example that demonstrates your approach?

It is so hard not to point you to the cover of my book since the image there encapsulates what might be seen less as either a democratic or an imperialistic leap of faith, propelled by a war mentality, than a leap of foolishness. That’s what caricature captures, in a rhetorical sense: combinations of wisdom and folly, sense and nonsense. That Uncle Sam is blindfolded further betrays a sort of metaphor for caricature as a means of making comic imagery into a looking glass for our ways of seeing—and our ways of not seeing.

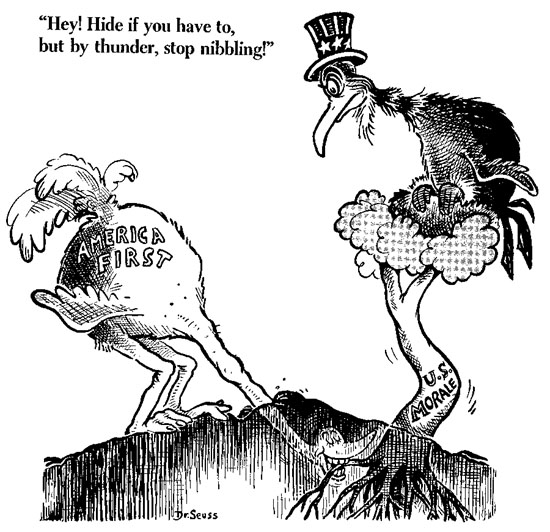

To say that the U.S. or any other nation has something like a “national character” is to suggest that we need to see ourselves in particular ways through the lenses of our historical principles and peculiar institutions. It is to imagine ways of being as they are impelled by ways of seeing various points of shared identification that exist, however blatantly or flagrantly or latently, in our collective consciousness. Such a comic imagination carries through every chapter of Caricature and National Character. We see it in the view of citizens at arms in Flagg’s “I Want YOU!” poster. We see it in Dr. Seuss’s image of an ostrich with its head in the sand. We see it in Ollie Harrington’s goad for us to look at who we are through the eyes of children. We see it in Telnaes’ entire framework for reimagining the prideful arrogance of a democratic nation that—much like the Uncle Sam that fills out the cover of my book—is on its way toward the Fall, precipitating the death of democracy on the precipice of a people’s own making.

I guess what I am getting at here is that my combination of cultural critique and rhetorical analysis relies on an assemblage of caricatures that grapple with ways of seeing how national character gets represented and recast for the sake of comic judgment. Variations on persistent themes matter a great deal here, which is why no single image will do.

.

What influence do you hope your book might have on conversations in humor studies? In other fields?

One hope is simply that readers either revisit or rethink editorial cartoons! They are still very much alive and, well, animated in our public culture.

I also hope that Caricature and National Character provokes renewed conversations about editorial cartoons, and caricature more broadly, in terms of public communication that is usually considered to be so utterly time-bound and so utterly topical that it is misrepresented as something to be seen once and then set aside. It is a fairly conventional perception that editorial cartoons provide a quick jolt or a laugh, but then give way to other modes of understanding around what is going on in the world. They are usually only conferred special purchase when they are controversial. A central element of my argument in this book as that caricatures in editorial cartoons and other comic illustrations are extraordinary precisely because of how ordinary they are in the conveyance of what matters to bodies politics both at specific moments in history and across the annals.

Then there is the aspect of caricature that goes beyond any discernible sense of humor. Perhaps scholars and other readers will look at the rhetorical force of caricature not just vis-à-vis human folly in the comic sense but also in terms of the hardline, hard-nosed, hard-hearted, and even fanatical ideologies that more than ever seem to lead so many of us to look at other people as little more than strangers and enemies in our midst. Along these lines, I would be delighted to discover that Caricature and National Character urges us to recognize that humor can certainly be used to preach to the choir, that it can constructively be used to sustain what Jim Caron dubs a “comic public sphere,” but that it can also be used, if not misused, to promote festive styles of hatred and crude carnivals of—to borrow a phrase from Hunter S. Thompson—fear and loathing. This latter dimension of humor requires our attention.

Finally, it is my sincere hope that scholars in other fields and readers beyond those interested in humor per se might turn to some of the arguments I make in this book to work out the variety of ways in which warism is baked into our official politics, our media cultures, our images and ideas about how to (in a weirdly Wilsonian way) keep the world safe for democracy. On the scholarly front, I wonder what people will think about where to go with comic imaginations if we are to turn toward rhetorical means of protecting and defending democratic institutions without recourse to the wiles of political officials or the soft powers of strong states. In more lay terms, I wonder what we might do to take pause with caricatures that situate our perspectives and opinions and beliefs on the comic edge of a distorted mirror that doubles as the oddly, distortedly, yet no less picture-perfect portrayal.

.

What trends do you see (or wish you saw) in humor studies? What do you hope for the future of the field?

There is such a rich tradition in humor studies of scholars really showcasing that which is humorous, comical, comedic, and the like, and doing so in a way that more often than not demonstrates the unique value that these modalities bestow upon humanity. I say this because I came to humor studies with an honest sense that others in the intellectual community shared my sense of just how vital what we study is to any understanding of everything from the progenation of rhetoric (let alone philosophy) through the establishment of so many societal divisions between upper and lower, sacred and profane, civil and brutish, etc. to the everyday dealings of human beings as homo ridens. I say this, too, because my hope for the future of humor studies is that it will continue on its trajectory of garnering more and more attention, more and more scholarly respect, and more and more acclaim as a site for dynamic academic inquiry.

Still, I do think there is even greater room for humor at the heart of cultural studies and rhetorical analysis. These days, perhaps more than ever, that which is humorous, comical, comedic, and the like is problematic—and I mean this in the Foucaultian or Deleuzean sense that something needs to be problematized—in that these things need to be subjected to new questions about why they are important, why they are relevant, and even why they are at issue with conventional ideas regarding what makes, say, this or that iteration of humor humorous, or even what makes humorhumor, and then again how we understand it as “good” or “bad” or somewhere in between. Some of the best scholarship on humor is not caught up in definitional or conceptual hairsplitting—at least not solely. Rather, it is tied to matters of politics, identity, communication, justice, judgment, and more. People are looking differently, for instance, at the comic spirits in activism and outreach that persist to deal with some of the darkest aspects of the human condition, i.e., racial bigotry. I and others are re-imagining the relationship between pleasure and pain as it is manifest in things like satiric films and stand-up comedy acts. I and others are also rethinking comedies of human survival in the face of literal catastrophe. This includes earthly devastations with regard to climates and species. It includes cultural crises such as racism, gun violence, and political divisions that traverse the boundaries of life on the streets, so to speak, and the policy measures that stem from seats of government. I can only imagine that humor studies will see redoubled efforts by scholars to connect their subjects and objects of interest to these all too real circumstances of life and death.

.

What’s next for you?

It feels a little strange to start talking about a second book just months after my first book was published, especially because I want to honor the work I did and the energy I expended to put the ideas of Caricature and National Character out into the world. But I have a hard time sitting still, and so am already in the initial stages of developing a new manuscript. It is very much in keeping with what I just mentioned about problematizing studies of humor, and it will be about what I am characterizing as instances when comedy goes wrong. The project will have a historical angle. However, it will be more focused on recent times than Caricature and National Character, which has its origin stories in the years leading up to and then carrying on from the First World War. Beyond the second book, I have a number of side projects in progress as well as a feeling that some rest and relaxation might serve me well in the waning days of summer! Nevertheless, as I often suggest when I sign off: more soon.

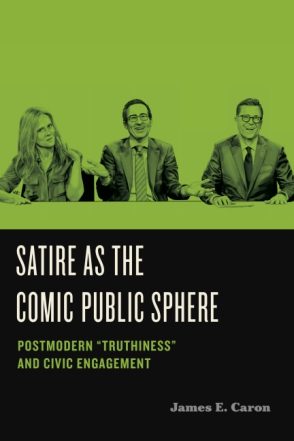

An interview with Jim Caron, author of Satire as the Comic Public Sphere: Postmodern “Truthiness” and Civic Engagement

Tell us about your start in humor studies. How and when did you begin pursuing it as a subject? who or what has influenced you as a scholar of humor?

My original topic for my dissertation was a folkloric look at the tall tale as a genre, but that morphed into the tall tale as a form in antebellum American comic writing and an influence on Mark Twain. So, in my academic career, I have always been interested in cultural artifacts that make people laugh.

However, the real turning point was being selected in 1989 for a National Endowment for the Humanities summer seminar on humor held at Berkeley and run by an anthropologist, Stanley Brandes. Those six weeks converted me to an interdisciplinary point of view. I spent more time in Kroeber Library (the anthropology collection) than any other library on the campus, mostly being fascinated by ritual clowns in traditional societies (my earlier folklore penchant had turned into an anthropological one). I’ve tried to maintain an interdisciplinary approach ever since.

.

Tell me about the genesis and creation of this project. What questions did you set out to answer, and how did your project develop to answer them?

The first impetus for the book came from submitting a proposal on satire to a projected collection of essays in the MLA teaching series. The proposal was rejected, but my interest in the topic had developed out of my Year’s Work reviews for Studies in American Humor because over the years I had tracked a growing set of publications on satire. Satire in the first decade of the twenty-first century was becoming a hot topic, which meant that for some time prior to writing the book I was immersed in the scholarly conversation about satire.

The second push came from a comment Judith Lee made about an introductory essay I had written for a special issue of StAH on postmodern satire. In the essay, I referred to satire as a special kind of comic speech act, and with her usual perspicacity, Judith said that that idea could be expanded. The foundation work I had done for the rejected proposal was then turned to use for the book, and the introductory essay on postmodern satire became the first draft of parts of the book.

I wanted to understand satire as a postmodern project in some of the artists that I had been faithfully watching on TV or in comedy specials. The entanglement of contemporary satire with the news was always a stimulus to my thinking. I also wanted to address the issues surrounding satire that I had zeroed in on when I wrote the proposal for the MLA collection: satire’s efficacy as a reform agent; satiric intent versus audience uptake; the importance of cultural context for understanding what the satirist intended and what the audience understood. I don’t see how one can tackle satire and not become enmeshed in these issues, and I use the examples in the book to work through them.

.

Your book—Satire as the Comic Public Sphere—develops a new approach to thinking about how satire, especially satire in the current media landscape, might operate. What do you hope that readers take from the book about how to understand satire?

The approach is new in part because I use speech act theory as a heuristic for contemporary examples of satire that play with the news, so I hope others find that tactic useful. The news as a focal point for some satire, however, points to the big claim in the book: that the best way to think about satire since the Enlightenment is to understand its connection to Jürgen Habermas’s concept, the public sphere. Satire parodies the public sphere and functions as its comic supplement. I think that framework makes sense, and I hope it persuades folks. Also, that framework enables understanding that satire functions as comic political speech, not political speech, which is how many scholars treat it. I suspect that there will be lots of resistance to that distinction, so I’ll be interested how it is processed in future scholarship.

The idea of a “truthiness satire” in a postmodern aesthetic provides a way to think about the recent cultural moment in which people, in particular politicians, offer “alternative facts” as competition in the public sphere to evidence and empirical science. Some folks call the resulting situation “post-truth,” but that misunderstands what has happened, implying that no one is interested in the truth any more, or that it can’t be formulated in a meaningful way. That position is essentially a bastardization of postmodern skepticism, which questions transcendental claims for a Truth, but does not doubt that facts exist and should be marshalled in any public sphere debate. I refer to the dismissal of facts and evidence as the “anti-public sphere,” and ridiculing it is the job of truthiness satire. The book is meant to demonstrate the poetics of that ridicule. I also probe the legitimate limits of that ridicule: when does the symbolic violence of satire descend into mere rants or screeds?

Finally, the first part of the book offers an extended definition of satire that is meant to be useful for other cultures besides American and for other time periods besides now. I hope that readers understand the dual goals of the book: one general and not time-specific, the other very time specific.

.

What influence do you hope your book might have on conversations in humor studies? In other fields?

Of course, what I really want is to alter forever the course of scholarly thinking about satire [insert laughter here]. My hope is that the definition worked out in the first part of the book spurs some thinking about satire in general as well as satire’s function in what some call “the project of modernity,” which includes postmodernity.

For the book’s second part, I hope that my examinations of contemporary satirists like Stephen Colbert, Samantha Bee, and John Oliver are persuasive, that demonstrating the dynamic relationship among the discourse of the public sphere, satire as discourse of the comic public sphere, and truthiness as the discourse of the anti-public sphere shows just how and why satire has become so prominent and so important in recent times.

My approach centers on the aesthetics of satire as well as its communicative force in the public sphere, but satire as a cultural artifact has an appeal across disciplines, including rhetorical theory, communication theory, political science and sociology as well as cultural studies, so I hope the book can contribute to conversations in those fields as well as humor studies. That would be in keeping with my original interdisciplinary interest in what makes people laugh.

.

What trends do you see (or wish you saw) in humor studies? What do you hope for the future of the field?

As a contributing editor and associate editor of StAH for about fifteen years, what I’ve seen is a huge and still growing interest in comic artifacts of all sorts by a wide range of disciplines. That has been exciting to witness and to be a part of.

The scholarly trend has moved away from a focus on literary comic artifacts to other media, especially film, TV, and standup. Gender studies and ethnic studies have also been growing in their influence. Earlier historical periods are somewhat overshadowed by examinations of the now and the recent past. The internet beckons as a largely unexplored territory: we are still trying to get a handle on humorous or satiric memes, for example.

I see the study of cultural artifacts that make people laugh as a growth area (to use market terms) for some time to come. The variety of disciplines that are investigating those artifacts is wonderful, and I don’t envision that letting up. There are now several journals devoted exclusively to scholarship on comic artifacts, and I would not be surprised if others showed up in the future. Moreover, there is still much work that can be done in earlier historical periods. Just trying to keep up with recent artistic production will provide work for many scholars as we conduct our various kinds of research across disciplines.

What’s next for you?

I have another book project centered on satire, partly finished. (I seem to be stuck to satire as though it were a tar baby, though I am not complaining.) My research question: what did satire in the US look like before Mark Twain came along and altered everything? There is a long tradition in the scholarship on American humor in the nineteenth century that sees everything through the lens of Mark Twain, and I want to explore another perspective. Mark Twain is like Mount Rainier in Washington state, so dominating the terrain that is it difficult to escape his shadow.

My research in this project centers on the 1850s, and I am happy to say that there is more satire there than is usually discussed, a perfect example of what might still remain to explore in earlier historical contexts. The star of that book will be Sara Willis Parton and her persona Fanny Fern.

Want to hear more? Jim spoke on this panel for the New Book Talks with the AHSA that focused on New Books on Satire.

The passing of Hal Holbrook

Tracy Wuster

Hal Holbrook passed away on January 23, 2021. In his honor, I am rerunning a post from several years ago. For more on Holbrook’s career, see Mark Dawidziak’s columns on Holbrook adding new material here and by the numbers here. And information on a documentary well worth seeing here.

I did not mention in the original post my experience seeing Holbrook perform as Mark Twain. As a scholar who studied Mark Twain’s performance, I was skeptical about seeing Holbrook–not because he is anything less than respected but because his version of Mark Twain is a different version than the one I studied. Holbrook’s Mark Twain is the older, wiser, white-suited-er version. The 1860s and 1870s version who lectured on platforms and lyceums across the country and in England was a different figure. So I wanted to get a mental image of that man in my grasp before seeing Holbrook.

I can’t remember the exact circumstances of the evening–my wife suffers through enough Mark Twain in editing and reading and living with me, so she was not there. And the tickets were more money than we had to spend easily, being end-stage Ph.D. candidates. I sat in the beautiful Paramount Theater in Austin, notepad in hand, ready to be skeptical, thinking, “I know Mark Twain as a performer. Let’s see what you got, Holbrook.”

He awed me. In the end, my notes were mostly empty. I laughed. I was moved. A passage of Huck Finn I had taught and read a dozen times unfurled in a whole new light. He did pretty well.

***

Hal performed the character of Mark Twain longer than Samuel Clemens. Much has been written and said about the importance of Mark Twain Tonight! and Hal’s performance as Mark Twain (not to mention his other wonderful acting work).

I want to offer my own story of meeting Mr. Holbrook in Elmira at the 6th International Conference on the State of Mark Twain Studies (which should be renamed, “Mark Twain Summer Camp,” in my humble opinion). For a graduate student, Mark Twain Summer Camp already meant meeting top scholars in the field–rock stars, if you will (if you are a nerd, that is). But Hal Holbrook is as big a star as you will find for Mark Twain fans, unless the man himself were to appear.

I was convinced that my panel would be empty, as it was scheduled opposite that panel at which Mark Dawidziak would be discussing “Mark Twain Tonight!” with Hal Holbrook in the audience. I was thus shocked and delighted when Lou Budd walked into my panel just as I began to give my paper (causing me to lose my place for a moment). For Twain scholars, you can’t get much more important than Lou Budd.

Hal Holbrook Speaking at Mark Twain Summer Camp

Photo Courtesy Patrick Ober

This video is the audio of Hal Holbrook’s brief remarks at the conference. Recorded by Patrick Ober and combined with images from the beautiful campus of Elmira College.

I had witnessed first hand the star power of Hal Holbrook the night before. After a full day of conferencing, I meandered down toward the evening’s banquet a bit early. In front of the building I found Shelley Fisher Fishkin and Hal Holbrook quietly talking. Shelley introduced me to Hal and mentioned I lived in Austin. As Hal began to say something, we were suddenly surrounded by a group of scholars who had been momentarily possessed by the spirit of teenagers at a concert when they spot the band backstage. That is to say, I was elbowed out of the way by a gray-haired college professor who had been star struck.

Hal was now surrounded by a group of admirers jostling for his attention. In my memory of the event, they are waving pictures for him to sign and taking photos with old-fashioned flash cameras. My memory may not be exact. As I stood there awkwardly outside of circle, a momentary gap opened and Hal said to me, as if our conversation had not interrupted:

“I was in Austin recently.”

I replied: “I know. I saw you perform.”

“When was that?”

I pondered a moment. “Spring.”

“What is it now?”

“Summer.”

“Sounds about right.”

And then Hal was engulfed by the adoring crowd of academics-turned-teenager.

The following night, the conference ended with a party at Quarry Farm, the summer house of the Langdon and Clemens family. I experienced another nerdy rockstar moment. While talking with Tom Quirk–no slouch of a Twain scholar himself–Lou Budd walked up and mistook me for a waiter. I will leave the story he told in explanation to his mistake out here, but it more than made up for any confusion.

After a wonderful dinner and a tour of the house, many people made the trek up the hill to the spot where Twain’s octagonal study sat. There are moments in one’s life that you know you will tell stories about for years–maybe 5 or 10 or even 20–but there are few stories you know, at the time, that you will tell for the rest of your life. For those of us who walked up the hill at Quarry Farm to the spot of Mark Twain’s study to smoke cigars, to sing songs, and to listen to Hal Holbrook tell stories, there is no doubt of the fact. A heck of a time, then, to test out the video function of my new camera. I wasn’t even sure it recorded in sound… but it did and in pretty good sound, too. Since a number of people couldn’t hear Hal speak, or were on the porch playing music, I have posted the below clips of his story of meeting Clara (and Isabel Lyon). I stopped recording as he described his heartbreaking meeting with Nina, which seems fitting in retrospect. I hope you enjoy. Click to see videos. Part 1–“So watch out!” Part 2–“I don’t know if it would book very well…” Part 3–“Clara was so dear to me, very sweet…”

Joe Csicsilla lighting Hal Holbrook’s Cigar Photo by Tracy Wuster (c) Tracy Wuster, 2012, 2015

Call for Proposals: Humor in America Book Series

HUMOR IN AMERICA SERIES

Penn State University Press

Series Editors: Judith Yaross Lee & Tracy Wuster

From Benjamin Franklin to Mark Twain, Mel Brooks to Richard Pryor, Our Gang to Inside Amy Schumer, American humor has time and again proven itself to be more than mere entertainment: it has brought cultural norms and practices in America into sharp relief and, sometimes, successfully changed them. The Humor in America series considers humor as anexpression that reflects key concerns of people in specific times and places.

The series engages the full range of the field, from literature, theater, and stand-up comedy to comics, radio, and other media in which humor addresses American experiences. With interdisciplinary research, historical and transnational approaches, and comparative scholarship that carefully examines contexts such as race, gender, class, sexuality, and region, books in the Humor in America series show how the artistic and cultural expression of humor both responds to and shapes American culture. The series will publish mainly authored volumes–although we will consider edited collections–and will appeal to audiences that include scholars, students, and the intellectually curious general reader.

Questions or submissions should be directed to the series editors at: leej@ohio.edu and

wustert@gmail.com

Judith Yaross Lee is Distinguished Professor of Communication Studies and Charles E. Zumkehr Professor of Rhetoric & Culture in the School of Communication Studies at Ohio University in Athens, Ohio (recently retired), and the author, most recently, of Twain’s Brand: Humor in Contemporary American Culture.

Tracy Wuster teaches at the University of Texas at Austin. He is the director of the Humor in American Project at UT and the executive director of the American Humor Studies Association. He is the author of Mark Twain, American Humorist.

Proposals should take the form of a three- to five-page proposal outlining the intent of the project, its scope and relation to other work on the topic, and the likely audience(s) for the book. Please also include a current CV. The editors note that although it is a logical fallacy to expect scholarship on humor to be funny, the best humor scholarship can be fun— and illuminate its exemplars’ comic spirit—while also being intellectually rigorous and a pleasure to read.

Series Editorial Board

Darryl Dickson‐Carr

Southern MethodistUniversity

Joanne Gilbert

Alma College

Rebecca Krefting

Skidmore College

Bruce Michelson

Emeritus, University of Illinois at Urbana‐Champaign

Nicholas Sammond

University of Toronto

Roseanne, Roseanne, and Where We Stand

An older post. One that Roseanne herself commented on. See comments.

Photo of Roseanne Barr by Monterey Media

Photo of Roseanne Barr by Monterey Media

What did I do the summer after I earned my master’s degree? I spent the better part of my free time on the couch watching Roseanne reruns. An F4 tornado unceremoniously concluded my last semester at the University of Alabama, and the frightful costs associated with cleaning up my life and property kept me solidly out of vacation mode. Things had been rough even before that. Those closest to me were experiencing layoffs, long-term unemployment, and bankruptcy. My own medical bills were piling up, and to top it all off I was growing out my bangs.

View original post 1,496 more words

Chuck Berry’s Promised Land

Matt Powell

Photo by Jean-Marie Périer, 1964

Chuck Berry was a walking contradiction. An inquisitive and highly intelligent student, born into a stable middle class family, who found himself incarcerated at 19 after an armed robbery spree with a broken pistol. A black man in his thirties in Jim Crow America who found a way to speak directly, successfully, to white teenagers. A cynic with an unyielding optimism. A sensitive, introspective man with a chip on his shoulder the size of a Coupe de Ville. A bitter man with a sly and relentless sense of humor. A loner and eternal outsider, who was at times the most beloved musician in America. A self-professed lover of performing live, who often seemed to consider his audience little more than a necessary annoyance. A consummate craftsman, who seldom bothered to rehearse or even tune. His only number one record, his worst song.

He saw the highest highs and the lowest lows of the American experience – from Bandstand to Lompoc, the colored window to the Kennedy Center – and he performed at times as brilliantly and as badly as an artist can. Through it all, he did everything on his terms.

Chuck Berry was the embodiment of America, and one of its greatest chroniclers and creators. Yes, he helped create rock ‘n’ roll and heavily influenced the Beatles and Rolling Stones and everyone after. But Chuck Berry’s genius is not tied to his chosen genre nor dependant on the successes of later British bands. His genius is independent, wholly American, self-contained, and has only solidified with time.

In the Archives: Thomas Nast and Santa Claus (1862-1890)

I can remember my first scholarly thought. Well, I should say that I can visualize the context of my first scholarly thought. Like a Polaroid of a younger me looking through a View-Master: I know that I saw something, and how, but can’t remember what.

I can almost replicate the place from memory, but will never replicate the time. Heraclitus, who was smarter than the average Greek, once wrote fragmentedly, “You cannot step into the same river, for other waters and yet others go ever flowing on.” True, but the Greeks widely preached the maxim to “Know Thyself,” and I remember helping my grandfather once, and being rewarded with a copy of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

To be precise it was The Annotated Huckleberry Finn, edited by Michael Patrick Hearn, copyright 1981 by Clarkson N. Potter, republished by

View original post 2,625 more words

A Fond Farewell

In October of 2011, Tracy Wuster took a chance and brought me on as poetry editor, even though I don’t have the academic credentials of my HIA colleagues.

In October of 2011, Tracy Wuster took a chance and brought me on as poetry editor, even though I don’t have the academic credentials of my HIA colleagues.

Drafting seventy blog posts on a subject I’m passionate about has been a privilege and a great learning experience.

As my monthly participation in this collaborative writing project comes to an end, and tumultuous 2017 becomes a memory, I’m feeling a bit wistful. The only American Poem that mirrors my emotions and feels apropos is aimed at the heart instead of the funny bone. It was penned by anthologist, translator, critic and poet, Louis Untermeyer, who was born in New York City in 1885, and died forty years ago today.

End of the Comedy

Eleven o’clock, and the curtain falls.

The cold wind tears the strands of illusion;

The delicate music is lost

In the blare of home-going crowds

And a midnight paper.The night has grown martial;

It meets us with blows and disaster.

Even the stars have turned shrapnel,

Fixed in silent explosions.

And here at our door

The moonlight is laid

Like a drawn sword.— Louis Untermeyer

Warmest wishes for the coming year and beyond. Thank you for your readership. Keep reading and writing poetry!

yours truly,

Raw Deals Revisited: The early novels of Thomas McGuane

Joe Gioia

Had Thomas McGuane’s life ended before forty, lost behind the wheel or in some small-town motel misadventure, he’d be remembered today with the same cultish sense of loss held for such late literary contemporaries as Fred Exley, Tom McHale, and George Trow. The epitome of the bad-boy author, McGuane spent his thirties, which nearly coincided with the 1970s, in the sway of heroic, largely picturesque excess. Somehow, against type, he survived.

His first novel, The Sporting Club, appeared in 1969 and launched a career of great length and depth. Nine others have followed, along with three short story collections, four filmed screenplays, and dozens of personal essays, published in three collections that address his life as a horseman and angler of some accomplishment.

His fiction’s larger themes are alpha male behavior, individual autonomy, and dread, and range from tales of criminal misadventure to sketches of contemporary life out west. A lot happens in all of them. The typical McGuane hero is a self-reliant, fairly skilled guy who, either by overestimating himself or underestimating others, screws up badly.

In righting his own ship, McGuane repaired to his Montana home, the Raw Deal Ranch, to raise horses and recast himself as a regionalist—a sardonic, graceful observer of small town Montana life, a social landscape that closely models the classic American tropes of heroic optimism and failure; his broad subject being: How the West Was Lost. For that he is one of our greatest, and certainly least appreciated, living novelists.

Raw Deal Ranch, to raise horses and recast himself as a regionalist—a sardonic, graceful observer of small town Montana life, a social landscape that closely models the classic American tropes of heroic optimism and failure; his broad subject being: How the West Was Lost. For that he is one of our greatest, and certainly least appreciated, living novelists.

But McGuane was at the start a satirist of broad national concerns. His first four novels exemplify a variety of comic work that was itself going out of style as he wrote. Absurdist in their aim, emblematic of higher disorders in the ‘60s and early ‘70s, the great comic novels of Heller, Bellow, Elkin, Vonnegut, and, yes, McGuane, along with the concurrent movies of Robert Altman, Arthur Penn, Mike Nichols and Woody Allen were consumed at the time by an avid public, homeopathic remedies against the madness of the era.

The impulse to laughter remains the animating spirit of McGuane’s work, even as he’s found varied and subtler means of expressing it. His enduring strengths as a writer, obvious at the start, remain: a flair for subtle observation, dramatic, sometimes violent, action, a cast of vivid, often desperate characters, and arch dialogue that’s at once plain and ornate. Even his bit players are alive on the page. Tying it all together all is one of the great narrative voices in American fiction, right up there with Bellow, Ring Lardner and Flannery O’Connor.

The Sporting Club is a very able, conventionally told story of the  increasingly lunatic goings-on at an upper-class hunting and fishing club in McGuane’s native northern Michigan. Its WASP membership, descendants of 19th century Robber Barons, run the gamut from conventionally uptight to barking mad.

increasingly lunatic goings-on at an upper-class hunting and fishing club in McGuane’s native northern Michigan. Its WASP membership, descendants of 19th century Robber Barons, run the gamut from conventionally uptight to barking mad.

Here, told in third-person narration, is James Quinn, a second-generation Detroit auto parts manufacturer in residence for the summer, and Quinn’s old partner in schoolboy crime, Vernor Stanton, whose immense inherited wealth allows him a perpetual juvenile revolt from the adult world of business and social standing. The novel’s tried-and-true satiric points include how easily social veneers are stripped away; the incompetence of a hereditary ruling class; and the loathing felt between it and its putatively respectful underlings. The latter are represented by Earl Olive, the club’s sinister groundskeeper whom Stanton gleefully goads into transformative violence.

The Sporting Club has a good first novel’s flaws: simple characterizations, reliance on set pieces, and over-determined gags (such as a club historian named Spengler). There is a gimmicky, multi-headed ending that includes a loony Lord of the Flies reboot, and the grand reveal of a very compromising antique photograph, found in a time capsule opened for the club’s centenary celebration.

CFP: Humor in America Conference, July 2018 in Chicago

Humor in America 2018

Call for Participants

Sponsored by:

American Humor Studies Association

Mark Twain Circle of America

Website: https://humorinamericaconference.wordpress.com

“Humor in America” will be held on the campus Roosevelt University in downtown Chicago from July 12-15. The conference will feature paper panels and roundtables on all aspects of American humor and/or any subject related to Mark Twain.

Please send proposals to americanhumor2018@gmail.com by February 1, 2018. Notifications will be sent by March 1. Please feel free to contact the conference organizers, Tracy Wuster, Larry Howe, and Pete Kunze, with any questions at americanhumor2018@gmail.com.

PAPERS:

Proposals for paper presentations of 15-18 minutes should consist of a 250-word proposal and A/V requests.

PANELS:

Proposals for organized panels of 15-18 minute papers moderated by a chair should include individual 250-word proposals, an overview of 100 words, a proposed Chair (not required), ad A/V requests.

ROUNDTABLES:

Each roundtable participant will speak for 7-9 minutes on a topic related to the larger theme (see below). Participants may present both a paper and participate in a roundtable, should space allow. If you wish to participate only in a roundtable, please indicate with your submission. Please submit a title and 100-word abstract if interested by February 1, 2018.

Roundtable topics:

–Theory, Methodology, and Practice of Humor Studies: New Directions

–MT and Graphic Humor: Icon and Caricature

–Gender and Humor: Can Men be Funny?

–Race, Ethnicity, and the Study of Humor

–Mark Twain and Today’s satirists: Colbert, Bee, and Oliver

–The Publics of Political Humor and Satire

–Violence in the humor of Mark Twain

–Humor, Comedy, and Historiography

We welcome proposals for paper presentations and panels on any topic related to American humor and/or Mark Twain, broadly conceived. Scholars across the humanities are invited to present research on any of the following topics (or others related to humor, comedy, laughter, etc., etc.):

- literary humor (including but not limited to Chesnutt, Fanny Fern, Parker, Faulkner, Melville, Vonnegut, Ellison, Morrison, Kingston, Beatty, Ephron, Sedaris, etc.)

- humor and gender, race, sexuality, class, religion

- stand-up comedy, sketch comedy, and other humorous performances

- radio comedy, television, and film comedy

- visual humor, comics, and graphic narratives

- podcasts, internet humor, memes, and other new media

- satire, ridicule, parody, and other forms of humor

- humor in “serious” contexts or works

- humor in regional, national, transnational, international, and other spatial contexts

- All topics related to Mark Twain (especially the following topics: Mark Twain language play, MT and Political humor, MT and stand-up, MT a and gendered humor, Laughter and the Color Line: Huckleberry Finn and Pudd’nhead Wilson, The Fantastic and The Comic in MT, The Comic Rhetoric of MT’s Speeches and/or Interviews)

We especially welcome proposals from scholars of color, junior scholars, and independent scholars. Graduate students attending the conference will be eligible for “Constance Rourke Travel Grants” to assist with travel funds. We highly encourage scholars to contribute to this fund. See the conference website for more information.

Attendees must be (or become) a member of the American Humor Studies Association or the Mark Twain Circle of America. Presenters will be highly encouraged to submit article-length versions of their work for possible publication in Studies in American Humor, a peer-reviewed journal published by the American Humor Studies Association since 1974 and in conjunction with the Penn State University Press since 2015. Presenters on Mark Twain will be encouraged to submit article-length versions to the Mark Twain Annual, published by Penn State University Press.

The conference registration fee will be $40 for graduate students, adjunct faculty, and independent scholars, and $75 for tenure-track faculty members.