Happy Halloween!

While watching scary movies this weekend, I noticed the similarities between horror and humor: suspense released through an emotional response, expectations build up and often end in surprise, and lots and lots of blood…

*Seven Graveyard Smashes…our own music editor, Matt Powell, on Halloween music.

*Michael Collier’s “All Souls”

*Will Rogers in “The Headless Horsemen”

*Halloween on Parks & Rec

*Halloween music, via Nine Kinds of Pie

*the origin of Halloween traditions…

*Werewolf Bar Mitzvah, spooky scary….

*A great version of Poe’s “The Raven” mixing humor and horror.

*Congratulations to the St. Louis Cardinals San Francisco Giants …via funny baseball quotes.

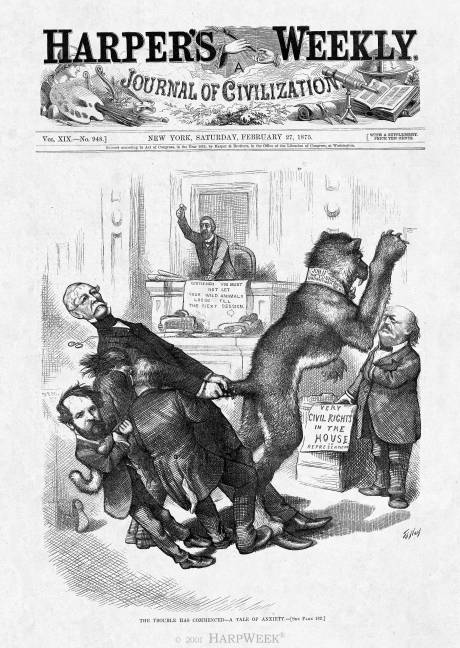

*Finally, some political cartoons from the past few years, as Halloween tropes are recycled to address new fears and old.

2014

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

**

*

*

*

*

**

*

*

*

*

**

*

*

*

**

*

*

**

*

*

**

*

*

*

**

**

*

**

*

*

*

*

**

**

*

*

*

*

*

*

**

*

*

*

**

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

**

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

**

*

*

**

*

**

*

**

**

**

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

**

*

*

**

*

*

*

**

*

*

*

**

*

**

2011

Stand-up at the Knitting Factory (Brooklyn, NY)

The Knitting Factory

361 Metropolitan Avenue, Brooklyn

Sundays at 9pm

As a graduate student, I’ve found that free time can be scarce. It can be difficult to justify the toll (both on your wallet and on your schedule) of a night seeing live comedy. But when you study stand-up comedy, you’ve got a built in excuse you make the time in the name of research. And if you’re doing your graduate work in New York, as I am, you have your pick of a number of scenes, venues, price ranges and styles of comedy from which to choose. With this in mind, I have decided to put together something of a living map of New York comedy. My plan is to make my way through the five boroughs to visit as many venues as possible, and to consider the relationship between New York and the ever-changing comic space.

I’m not starting with a landmark venue—or rather, a landmark venue for stand-up. I’ll certainly get around to profiling some (all?) of the great spots to see comedy around New York, but I decided to start with a local Brooklyn show, and I’ll tell you why: Hannibal Buress and, to be perfectly honest, the anticipation of a great surprise guest. Hannibal is a Chicago native who has made a name for himself as a stand-up and a writer (SNL from 2009-2010, 30 Rock beginning the following season). Fans will notice his jokes making their way into 30 Rock scenes with some regularity, as well as his recurring stint as a homeless man on the show. He never mentions his writing credits by name during his stand-up sets, but it’s safe to assume the growing audience (the Sunday shows are now frequently standing room only) is familiar with his work. In fact, the crowd is comprised of a significant number of repeat customers.

If I wanted an all-star lineup, I could go to a traditional venue to increase my odds of catching some great comedy (or, failing that, some big names), but there’s a charm to the smaller venues, and the anticipation of a lineup change. And while this can happen at any comic venue, large or small, I can rest assured that a precedent already exists.

These Sunday night shows have a unique neighborhood-comedy-show feel, mixing the hipster Williamsburg set with local and (inter)nationally touring comics. The Knitting Factory’s Brooklyn space has the bare design and pseudo-industrial feel common to some Williamsburg/Bushwick performance spaces. Immediately past the door is the bar and seating area—sparsely decorated without the kitschy wall hangings or adornments of a themed bar—and a small stage stashed to the side. (I took this picture just before a recent show)  Between the stage and the bar is a swinging door, which leads to the bathrooms and the concert venue. As a result of this design, comics performing during the Sunday night show are forced to confront a flowing stream of customers making their way from the concert venue to the bar (and back) with the feigned spontaneity of a comic doing the same crowd work in one set after another.

Between the stage and the bar is a swinging door, which leads to the bathrooms and the concert venue. As a result of this design, comics performing during the Sunday night show are forced to confront a flowing stream of customers making their way from the concert venue to the bar (and back) with the feigned spontaneity of a comic doing the same crowd work in one set after another.

While this design may be distracting, The Knitting Factory was founded as a multi-purpose performance venue. Michael Dorf opened the first Knitting Factory in 1987 as an art gallery and performance space meant to join together different performance media. The initial space in Manhattan programmed various styles of performance on different nights—poetry and spoken word on Wednesdays, jazz on Thursdays, etc. [This kind of audience fragmentation is fairly common in comedy clubs, too—e.g feature nights dedicated to different races and ethnicities] As a result, you get a fairly mixed crowd of local patrons watching whichever Sunday night game is on the two televisions (which are turned off as soon as the show begins), anyone sitting at the bar, those wandering concert-goers, and those actually there to see Hannibal and his guests.

Humor in America is on Twitter!

Follow us at @HumorinAmerica! Every blog post will automatically be added to the Twitter feed. Click the handy dandy “Follow” button on the right side of the screen to subscribe with your Twitter account. For those wary of a full fledged commitment to Twitter, you can come here see our latest tweets in the sidebar without signing up.

Occupy Wall Street in Political Cartoons

Tracy Wuster

While not following Occupy Wall Street as closely as I would like due to a hectic schedule, I have noticed the role of humor in the protests, especially in the signs.

As M. Thomas Inge’s earlier post pointed out, political cartoons have long been a major form of humor in American political discourse. With this in mind, here are few cartoons that I have found worth considering: (please also see Halloween specific Occupy cartoons here)

from: DailyKos cartoons (more here)

Mike Luckovich from The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

See slideshow of cartoons here.

Please comment on cartoons and post links to others in the comments.

(c) 2011, all cartoons are copyrighted and used under fair use

Five Subjects Behind: Some thoughts on grunge, time machines, and “Clam Chow-Dah!”

by Tracy Wuster

On January 11th, 1992, I gathered with a group of friends to watch Saturday Night Live, our usual Saturday night activity as high school sophomores. This was a special night. Nirvana was playing, and we were living just north of Seattle. Grunge was our thing: flannel, mosh pits, and, most of all, music.

This was the episode on which the band played “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” thrashed their instruments during “Territorial Pissings,” and kissed each other during the closing credits. The band’s anarchic spirit expressed not only our (possibly exaggerated) teen angst but also the humor of destruction, noise, and pissing off parents and other authorities that went hand in hand with the angst.

But, oddly enough, what I remember most from that episode of Saturday Night Live is not Nirvana’s performance but a sketch featuring the host Rob Morrow. The sketch is entitled, “Five Subjects Behind,” but I have always referred to it as “Clam Chow-Dah!”

Watch:

http://www.hulu.com/watch/281921/saturday-night-live-five-subjects-behind

In the sketch, Morrow is at a diner with two friends–a man and a woman. As the conversation proceeds, Morrow awkwardly and consistently returns to previous subjects with a punchline now hopelessly outdated, interrupting the flow of conversation to the increasing consternation of his friends. At one point, the character played by Mike Myers mentions Boston and clam chowder. After several subjects go by, Morrow bellows out: “Clam Chow-dah!” in a Boston-esque accent, and then awkwardly recreates the context, defeating the humor of the comment and, in fact, forcing an awkwardness that might be described as “anti-humorous.”*

Introducing our Poetry Editor

We are pleased to introduce Caroline Sposto as our poetry editor. She will be posting humorous poetry on a regular basis. Welcome.

Caroline Zarlengo Sposto has a B.A. in English from The University of Colorado and an M.S. in Electronic Media from Kutztown University. She spent the majority of her professional career as co-founder and managing partner of Sposto Interactive digital agency. She sold her interest in the company in 2009, returned to creative writing and has since published several poems, short stories and essays.

John Updike (1932 – 2009) crafted meaningful works about the complexities of mainstream American culture for more than five decades. Though best known for his protagonist, Harry Rabbit Angstrom, this longstanding critic, chronicler, and champion of our middle class first published light verse in the New Yorker. While his witty, poetic take on post-war society is incisive and satirical, it glows with amiable affection for its subject instead of haughty contempt or caustic cynicism.

His 1955 poem, “To an Usherette” ran in the New Yorker during the cold war. Its quirky characters, clever diminutives, unusual rhymes and musical meter provide dazzling, accessible fun at face value. Yet between the lines, this poem is filled with rich commentary about a pent-up and often-hypocritical era.

Levittown-inspired developments were changing the American landscape. A decade had passed since Rosie the Riveter had traded factory work for suburban domesticity or a marginalized “pink collar” job. Television was fueling an unprecedented level of consumerism, while fine-tuning our standards of social conformity. This was a period of acute class-consciousness, mass upward mobility, stifling corporate culture and commercially driven cookie-cutter sophistication. Moreover, behind closed doors, millions of American couples were quietly coping with the fallout from over-urgent, wartime marriages.

What underlying messages speak to you through this charming poem? Share your insight. Tell me what you think. Enjoy!

To an Usherette

Ah, come with me,

Petite chérie,

And we shall rather happy be.

I know a modest luncheonette

Where, for a little, one can get

A choplet, baby lima beans,

And, segmented, two tangerines.

Le coup de grâce

My pretty lass,

Will be a demi-demitasse

Within a serviette conveyed

By weazened waiters, underpaid,

Who mincingly might grant us spoons

While a combo tinkles trivial tunes.

Ah, with me come,

My mini-femme

And I shall say I love you some.

All material except for poem, (c) 2011, Caroline Sposto