Category Archives: Laughing to Keep from Crying

Humor in the Age of Trump

Tracy Wuster

Having been distracted from the study of humor by the spectacle of politics for the past six months to a year, I have yet to put together a cogent response to the question of the role of humor in the age of Trump. For many, it seems, there is little to laugh at in such a time–at least not the laughter of pleasure or enjoyment. The humor that comes with satire, yes, but I have not seen much pro-Trump humor. Maybe I am not looking in the right place.

Here I want to gather and direct you to a few pieces that I have found interesting on humor and its role now. Please feel free to direct us toward others in the comments.

MAGGIE HENNEFELD / UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA

…Comedy, however spiteful, has always possessed a special power to reveal that the emperor has no clothes. Satire defeats fear with laughter. As Jon Stewart put it in a 2010 MSNBC interview with Rachel Maddow—about the destructive impact of news entertainment on journalistic standards—what “satire does best…is articulate an intangible feeling that people are having, bring it into focus, say you’re not alone. It’s a real feeling. It’s maybe even a positive feeling, a hopeful feeling.”3 Unlike the smug laughter of cynical disavowal, the stinging laughter of pointed satire can actively participate in transforming our perception of reality. Since reality is a construct—equal parts unknown trauma and Celebrity Apprentice—it is therefore ripe for the molding, and ours for the seizing….

“Hold on—that’s a trash fire. Over there is Trump’s Inauguration speech.”

LETTER TO AMERICA

BY MICHAEL P. BRANCH…First of all, America, never forget the immense power of humor to expose misguided values and destructive practices. Satire is as vital and as useful now as it was when Aristophanes ragged on Socrates in The Clouds back in 423 BC. You remember that gut buster, don’t you? Well, we still have plenty to learn from Swift and Johnson, Bierce and Twain, Orwell and Huxley. Satire is not only funny but also enormously forceful and effective—and, human nature being what it is, the comic exposure of vice and folly has the added benefit of offering great job security. America, I know you feel like you’re on the defensive, that even as you try to inspire, persuade, and reform, you secretly fear that you are now a voice crying in the wilderness. The satirist, by contrast, remains on the offensive, challenging established power structures, revealing their absurdity or violence, forcing villains to account for themselves. Orwell was right that “Every joke is a tiny revolution,” because satirical humor is the enemy of established power—especially power that lacks moral leadership. The satirist’s work is the serious business of striking into that troubling gap between what our ideology promises and the often disappointing outcomes our choices actually produce. We don’t call them “punch” lines for nothing….

Political Correctness Isn’t Killing Comedy, It’s Making It Better

Diversity Among Comedians and Audiences Makes Room for More Laughs

BY REBECCA KREFTING

…What’s notable about these new, louder voices is that they aren’t stifling free speech (that bludgeon so often used by incorrectness defenders). They’re creating more. Comics such as Jim Norton may criticize the internet outrage gang for spending too much time railing about matters that are inconsequential, namely jokes told by comics. Upon closer examination, however, a lot of these “petty” conversations speak to issues of great significance in our society like how we portray and treat historically disenfranchised groups.

Does some of the outrage go too far? Yes. Will fear of backlash lead to some performers self-censoring their material? Perhaps. (Though you’ll note that most of these complainers aren’t exactly being silenced.) But it’s a false presumption that being more mindful when it comes to producing humor that punches down will somehow create comedy that’s less funny. If anything, it makes it smarter….

Comedians in the Age of Trump: Forget Your Stupid Toupee Jokes

But these sorts of jokes about him fail to even begin countering the disastrous impact he’ll have upon the world. Because the problem isn’t that he’s unmockable; it’s that he’s too dangerous to simply mock. The saint of the so-called “alt-right,” the man who “tells it like it is,” supports free speech only so long as he isn’t the butt of it. His rhetoric is grounded in hate. But what’s most dangerous is that his entire identity is grounded in the paranoid idea that he, a millionaire who answers to no one — the very definition of a punch-up comedy target — is somehow the victim, and that making fun of him is in fact punching down. The best comedy imagines new, better worlds by laughing at the old, current one. But how do we laugh at this world when it’s run by a man who not only can’t take a joke but would be giddy at the prospect of taking away our right to make them at all?

The Fall of Trump: A New Image of the Donald

Tracy Wuster

In September, I collected a range of images of Donald Trump in “The Summer of Trump: Clown, Gasbag, Monster, Anti-PC Hero, and Other Images of THE DONALD.” Like many people watching the spectacle of the presidential primary season, I felt that surely the Trump spectacle wouldn’t last, something that Trump said would surely lead him to be a footnoted joke like Herman Cain, Michelle Bachman, or Rick Santorum. I was wrong.

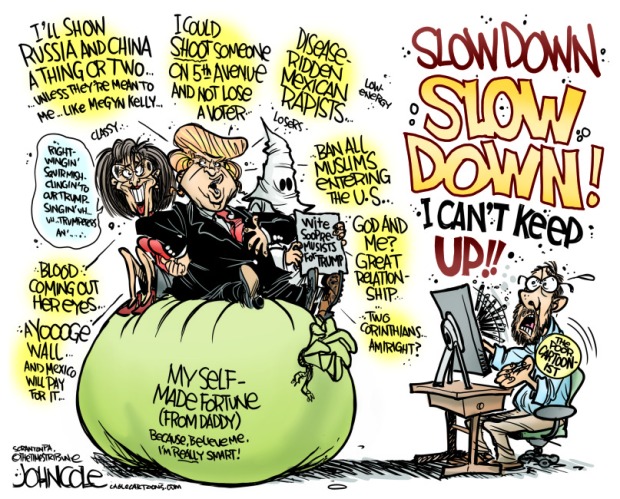

On that post, I promised to keep up with the images, but my fatigue at all things Donald kicked in after an update or two. And, for the most part, the images were fairly consistent–clown, gasbag, misogynist, racist, etc., with the occasional pro-Donald cartoon coming in from the right-wing. As this cartoon shows, Trump’s constant media presence and proclivity to shoot off his mouth surely keeps cartoonists busy.

But over the course of the fall and into the winter, one image started to recur more and more–and image that seems to go beyond the normal confines of the relatively safe satire of political cartoons: the image of Donald Trump as a fascist.

Portraying Trump in relation to Nazi or general fascist imagery seems to me to be a step beyond how cartoonists portray tend to portray major political figures. A google image search for such images for Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, and George W. Bush turn up only scattered images.

Especially after Trump’s comments about banning Muslims from the U.S., images connected him with fascism were not scattered, they were prominent. Here are the images:

All images copyright of their creators.

And in February and early March, we have the link between Trump and the KKK/David Duke.

Thoughts on Charlie Hebdo

Humor in America

Those of us who study humor, and I would think that many people in general, have spent a lot of time the past few days thinking and reading about the meanings of the Charlie Hebdo Massacre in France. We have collected here a number of the articles, cartoons, videos, and other pieces that have been helpful and/or provocative, although this list is in no way exhaustive. Feel free to add suggestions in the comments.

*The Onion’s brilliant piece on the fear of publishing anything on this subject. Also, this and this from the Onion.

*A few cartoons from the last week: Tom Tomorrow, Khalid Albaih, the Atlantic Monthly,

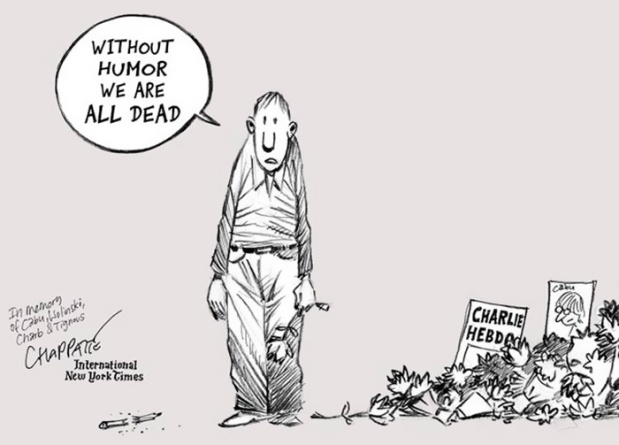

by Patrick Chappatte (http://fusion.net/story/37267/cartoonists-respond-to-the-charlie-hebdo-killings/)

*And more collections here and here and (and why the media should pay cartoonists here).

*Joe Sacco’s provocative cartoon “On Satire“: “In fact, when we draw a line, we are often crossing one too. Because lines on paper are a weapon, and satire is meant to cut to the bone. But whose bone? What exactly is the target?”

*Ruben Bolling of “Tom the Dancing Bug” “IN NON-SATIRICAL DEFENSE OF CHARLIE HEBDO”

*The Daily Show on the tragedy.

*Ted Rall, “Political Cartooning is almost worth dying for.”“Which brings me to my big-picture reaction to yesterday’s horror: Cartoons are incredibly powerful.

Not to denigrate writing (especially since I do a lot of it myself), but cartoons elicit far more response from readers, both positive and negative, than prose. Websites that run cartoons, especially political cartoons, are consistently amazed at how much more traffic they generate than words. I have twice been fired by newspapers because my cartoons were too widely read — editors worried that they were overshadowing their other content.”

*Unmournable Bodies, by Teju Cole: “But it is possible to defend the right to obscene and racist speech without promoting or sponsoring the content of that speech. It is possible to approve of sacrilege without endorsing racism. And it is possible to consider Islamophobia immoral without wishing it illegal.”

*”Charlie Hebdo is Heroic and Racist” by Jordan Weissmann. “So Charlie Hebdo’s work was both courageous and often vile. We should be able to keep both of these realities in our minds at once, but it seems like we can’t.”

*Were Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons racist? This says yes. This provides much needed context on the difficult question of cultural norms. NYT on the context of Charlie Hebdo and French satire. Some explanation of some of the controversial Charlie Hebdo covers. And more context on the satire of the magazine.

Maya Angelou: “If you don’t laugh, you’ll die…”

Tracy Wuster

All Americans are–or should be–aware of the cultural importance of Maya Angelou in documenting our nation’s history and her own experience through poetry and prose. I will leave it to other sources to remind us of and to celebrate her contribution to American letters and life. But here, I want to simply bring forward a few things Angelou said about the importance of humor and laughter that remind us of the importance of joy and laughter in the struggles against bigotry and the efforts to create a meaningful life for ourselves and those we love.

“My mission in life is not merely to survive, but to thrive; and to do so with some passion, some compassion, some humor, and some style”

“I don’t trust anyone who doesn’t laugh.”

“I’ve learned that even when I have pains, I don’t have to be one.”

If you have only one smile in you, give it to the people you love. Don’t be surly at home, then go out in the street and start grinning ‘Good morning’ at total strangers.”

“When I look back, I am so impressed again with the life-giving power of literature. If I were a young person today, trying to gain a sense of myself in the world, I would do that again by reading, just as I did when I was young.”

“The main thing in one’s own private world is to try to laugh as much as you cry.”

“I’ve learned that you shouldn’t go through life with a catcher’s mitt on both hands; you need to be able to throw some things back.”

“If you don’t laugh, you’ll die… Against the cruelties of life, one must laugh.”

“My wish for you is that you continue. Continue to be who and how you are, to astonish a mean world with your acts of kindness. Continue to allow humor to lighten the burden of your tender heart.”

And don’t forget Maya Angelou’s short-lived prank show–“I know why the caged bird laughs!”

See also Laughspin’s tribute.

WHEN I THINK ABOUT MYSELF

When I think about myself,

I almost laugh myself to death,

My life has been one great big joke,

A dance that’s walked

A song that’s spoke,

I laugh so hard I almost choke

When I think about myself.

Sixty years in these folks’ world

The child I works for calls me girl

I say “Yes ma’am” for working’s sake.

Too proud to bend

Too poor to break,

I laugh until my stomach ache,

When I think about myself.

My folks can make me split my side,

I laughed so hard I nearly died,

The tales they tell, sound just like lying,

They grow the fruit,

But eat the rind,

I laugh until I start to crying,

When I think about my folks.

In the Playground of Parody

We’ve all had that heart-stopping moment going through airport security, when our bag (or the bag of someone near us) is swept off the belt and meticulously torn apart by grim TSA personnel. Everyone lucky enough to have already passed through watches out of the corner of their eye as they hurry to get their stuff and get away — just in case. We all know that those orderly lines are just a stampede waiting to happen.

And we’ve also all felt the intrusiveness of a TSA agent who got a little personal and over-aggressive with the wand or with a manual search because the scanner picked up the quarter we forgot was in our breast or pants pocket. We know that vulnerable moment of personal terror when we realize that our line leads to the scanner that requires us to raise our hands over our head rather than just walking through — in spite of the fact that our belt, now riding in the gray tub, was the only thing keeping our pants up. We know that we’re just regular folks, but it feels like a violation when we’re singled out for further screening. Terrifying, too, as we know that with the threat level at Orange or above, they aren’t messing around; protestations of innocence will be utterly ignored. And forget it if you even look like you fit into one of the “terror profiles.” You’re positive, right then, that you’re about to find out just how tenuous our freedom actually is. Gitmo, here we come.

This spring, director Roman Coppola (son of Francis Ford Coppola) teamed up with comedian and actress Debra Wilson to play on these collective fears and feelings of vulnerability in — of all things — an Old Navy commercial. The ad has roused much comment, running the gamut from its dismissal as racist trash and egregious minstrelsy to its celebrations as hilarious, as brilliant parody or satire.

Wilson, an eight-year veteran of MADtv, plays a TSA agent who tries to spice up a job that is both high-stress and boring, injecting a little humor to keep herself awake and alert as she’s encouraging passengers to follow the rules and keep the lines moving along:

“Sir, keep your pants on. Ma’am, water is a liquid all over the world, so that’s H – 2 – no!”

The characterization is pitch perfect, balancing just the right amount of bored stoicism and aggression with humor. Then the comedian takes it over the top:

So, is it a brilliant spot or is it a particularly egregious bit of corporate racist fantasy, blackface minstrelsy haunting us still?

The answer, perhaps, is both.

In creating characters, Debra Wilson draws a firm distinction between doing “impersonations” and “impressions.” In impersonation, her goal is to “be” the person she’s impersonating, to make someone feel that they’re seeing that person, actually meeting that person. Impressions, on the other hand, are presentations of “social perception” — take-offs of what people see or want to see, of public persona and behaviors.

Impressions are parody, and Wilson says, “I am there to represent what most people are saying, most people are thinking, most people are reading about.” Her intent is not to represent the real person, but rather to parody what is acted out in the social arena, to parody and caricature the public actions of a person, or the public’s perception of that person, rather than the person herself. The object of the impression, then, is to hold the public image, actions, and social perceptions up to a mirror of parody.

Wilson further argues that there’s “no point in doing it if it’s not a playground.” She loves complex situations, with multiple levels of actions, opinions, perceptions clashing, which offer her “the opportunity to have a larger playground.” (See interview below, of Wilson’s 2010 appearance on the Gregory Mantell Show.)

So what is the “playground” of parody offered in this commercial featuring Connie, the TSA agent? Continue reading →

Eskimo and Ordnance

by Richard Talbot

The Eskimo languages, it is said, have dozens of different words for snow and this is very useful to the Eskimo. Reveal this fact to grownups and they will seem surprised, but tell this same thing to a boy of ten and he will only signal satisfaction at learning that someone has had the good sense to name the different kinds of snow that he is already familiar with. Every boy growing up in Minnesota knows that all snow is not the same. While boys may not know all the different names for these snows, they do know them by sight and all of their different uses.

There is the kind that crunches beneath your boots when the temperature is right; it’s good for snowballs, but is so light that it has only a medium capacity for joy and destruction when aimed at your brother. There is the heavy, wet kind that soaks your mittens through and is a lot better for the same thing. And then there is the dry hard-packed kind that is especially good for cutting into blocks when you need to make a snow fort. This is the kind that has a light layer to the top that gets picked up by the wind and is wistfully swirled about all around in snow devils. It sparkles in the light and gives off the prettiest rainbow luminescence when the angle of the sun is just right.

Young boys know a lot of other things as well, things that military men call tactics and ordnance. Boys know about these things, too, but they don’t know what their proper names are. But know them they do, and they can tell you exactly how far a snowball of a given kind will go when it is launched. How it will behave when it hits its target. How its target will behave when he gets hit. They can anticipate their enemy’s firepower as well, and plan the best escape route once they have launched their joyful weapons of destruction. Boys know a lot about snow, tactics and ordnance.

When I was a boy I loved the winter, but there was one time in particular that was the best of all. That was Christmas vacation. Everything about it was perfect; no school, snowy days and nothing to do.

“A University Course” on the Value of Satire in a Crazy World

Life, fundamentally, is absurd. Every day we encounter opinions, actions, experiences, or events that make us wonder whether we are crazy, whether the world is — or whether there is sanity to be found anywhere.

Satire provides a vehicle for holding such contradictory world views in simultaneous suspension — a way of shifting the ground to contain the uncontainable, to allow the simultaneous expression of unresolvable and sometimes ambiguous opposites. While some argue that students struggle with recognizing satire or analyzing it successfully, I think that the struggle is more than worth it — and I find that once students move away from the idea that there is one right answer, they truly enjoy the power of satire to open their minds to new possibilities, uncertainties, or perspectives, without the overwhelming despair that sometimes comes from a “serious” or “straight” presentation of difficult material or moral conundrums. As I have argued in a previous posting, the power of satire lies not in its unambiguous moral target, but in its propensity to force us to make a choice about what that target (or those targets) might be. To both force critical thinking and allow us to laugh painfully, or laugh it off — if we so choose. Because sometimes, laughing is the only way that we can keep moving, keep functioning in an upside-down world.

In the late spring of 1923, W. E. B. Du Bois found himself in such a place. About six months earlier, the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill “died” in the Senate, the victim of a filibuster and a deeply divided nation, after four years of Congressional debate and re-working of the bill in committee and on the floor of the House. The bill had been introduced by Congressman Dyer of Missouri in 1918, and its defeat was marked that spring by a lynching in his home state, the communal and extra-legal murder of James T. Scott in Columbia, Missouri. Scott was an African American employee of the University of Missouri, and the lynching was noted nationally for the presence of students — and particularly, 50 female students — though reports state that none of them actually “took part,” but were spectators. While Du Bois had often responded to previous lynchings with a trademark sarcasm and satirical outlook, the defeat of the Dyer Bill and the lynching of Scott seem to bring a new level intensity to his satire — a satire marked by both despair and desperate hope.

The tenderness of this drawing by Hilda Rue Wilkinson, with its peaceful evocation of family and normalcy makes a stark contrast with Du Bois’s opening salvo.

The cover of that June’s issue offers no clue as to the intensity of the subject matter on its opening page. The drawing is peaceful, a mother and her daughter with flowers against an open and non-threatening backdrop of hills, trees, and sky. It is an intimate moment, and the mother frankly and calmly returns the spectator’s gaze, while the little girl seems off in her own thoughts, undisturbed by the watcher. The title of the magazine, The Crisis, jars a little, its meaning in opposition to the peaceful, domestic feeling of the artwork.

But that moment of dissonance becomes cacophony when the page is turned, revealing a scathing and brilliantly, horrifically, and shockingly funny satire entitled “A University Course in Lynching,” penned by W. E. B. Du Bois.

The page is clearly marked “Opinion” in bold letters rivaling the title of magazine, Du Bois opens the editorial by proclaiming that “We are glad to note that the University of Missouri has opened a new course in Applied Lynching. Many of our American Universities have long defended the institution, but they have not been frank or brave enough actually to arrange a mob murder so that students could see it.” He notes that the lynching of James T. Scott took place in broad daylight and that at least 50 women were in attendance, most of them students. Du Bois goes on to satirically praise the University’s efforts in a style that recalls Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal”: “We are very much in favor of this method of teaching 100 per cent Americanism; as long as mob murder is an approved institution in the United States, students at the universities should have a first-hand chance to judge exactly what a lynching is.”

He describes the case in brief detail, stating that “everything was as it should be” for a teachable moment. Scott “protested his innocence” against that charge that he had “lured” and sexually assaulted a 14-year-old girl “to his last breath.” The father has “no doubt” of Scott’s guilt, but “deprecates” the violence of the mob. What Du Bois does not say here was that the girl’s father, an immigrant professor at the University, actually tried to speak up and stop the lynching, but chose to be silent when the crowd threatened to lynch him as well. Du Bois concludes:

Here was every element of the modern American lynching. We are glad that the future fathers and mothers of the West saw it, and we are expecting great results from this course of study at one of the most eminent of our State Universities.

Suddenly, this little girl and her mother are in a different world.

A world upside-down. A world in which communal murder is officially condoned, due process is suspended, and lynching is not a phenomenon of a wicked South, but of the West.

My students notice different things every time I teach this satire. Partly because Du Bois’s piece also mentions a lynching at the southern University where I teach, my students often focus on that aspect, on the power of the satire to enlighten them about history they did not know, history that hits close to home. This week, however, my students focused Continue reading →

Jim’s Dilemma

Your pa, he says to me that I need to come and help you understand why he had to go away, why he had to join the Missouri Colored Regiment.[i] Says I was good at explaining and good at leaving my own self, and so I might as well be the one. But you knows what your pa’s doing, don’t you? You knows that he joined up so’s you all be free when he come back. That’s cause you listen good, child.

Your pa, he never did understand, though, about why I went away. Never did let me tell the whole story. Always said I loved that white boy better’n him. Never did understand. But that’s my fault, I reckon. Or maybe that’s just the way it goes.

Ole missus, that’s Miss Watson as was, she moved in with her sister, see? And I hads to go with her; didn’t have no choice, though that meant I was 20 miles or more from your nanny and your pa and your aunt ‘Lizabeth what as died before you was born, 20 miles instead a just a few. Used to come see them most every night, but after that— Johnny—your pa—had to be the man of the house whiles I was gone—much as slavery lets you to be a man. But love that white boy more’n him? Huhn! I tell yah—first words I says to that white boy, I says

“Name’s not ‘nigger,’ boy. Name’s Jim. And I lay I’ll teach you to know it.” Those was the first words I said to him.

Huh? You’re right. Told you, you’s a smart boy, and I admit it. Them’s the first words I thought when that little white trash moved in and got dressed up in all the fancy clothes and done called me out my name though he just crawled right outten a hogshead his own self. What I said aloud was “Yassuh, young massa?” Man’s gotta know where the corn pone comes from. It’s a tough world, it is, child, and don’t you forget it.

The boy weren’t so bad, though, as white folks go. Fact is, I believe he had a good heart in there when it weren’t messed up and confused. He told some of the story round about here, when that Tom Sawyer would let him talk. And Huck, he told the truth so far as he could, I guess. As he says, we all gots some stretchers in us. But he was the only white man I ever know that even tried to keep his word to old Jim. Only white man I ever know that thought a word was a something to keep, when talking to a black man. Most of them’d sooner lie than look at you. But you know, they don’t really like looking now, do they?

Huck, he weren’t so bad, though. And he did try. But with a dad like his’n and that Tom Sawyer always raisin’ Cain and messing with his head, calling him chucklehead when he got a fair point an’ such truck as that. Huck never had no chance. But he tried, and I got to give him credit for trying. He was a good boy, take it all in all.

I done told you the story lots a times, about the time I runned.[ii] Had to. You know that. The devil he got in me. And old missus, she got scared. Was gonna sell me down to Orleans, she was. Never woulda seen your pa or ‘Lizabeth again. I lit out mighty quick, made a good plan, too, but there’s people everywhere, on account of they thought Huck done been killed. They was crawling all over both sides of the river.

I took my chance in the dark—you knows the story—how I hid in the driftwood, then latched onto the raft. I needed to get far away, and I knowed it. Heard all day from where I was hiding in that cooper’s shack about how Huck‘s killed on the Illinois side. Knowed oncet they realized I was gone, they’d blame me for it. Ridden by witches and with the devil’s own coin, they’d never believe it weren’t me, and they’d know I’d lay for Illinois. Where else a man going to go? It’d be like that black Joe in Boone County what killed that white trash with de axe, or that Teney in Callaway that they said killed that woman.[iii] I’d never a seen the inside of a jail.

But I didn’t have no luck. When the man come toward me with the lantern, there weren’t no use for it; I struck out for the island. Had to lay low, ‘cause they was hunting Huck, and pretty soon, they was hunting me, too. Couldn’t get much to eat. Knew I needed to swim for the Illinois shore afore I was too weak from hunger, but they was hunting too hard. And push come to shove, I kept thinking ‘bout your pa, and about poor little ‘Lizabeth, and somehow I couldn’t leave. My head was just a busting and so was my heart. Lit myself a fire to keep warm, made sure it didn’t smoke, but I kept seeing ‘Lizabeth’s eyes looking into mine. Wrapped the blanket round my head to shut them out, but that didn’t make no matter. Finally done fall asleep, though.

First thing I saw when I wakes up was that there dead white boy, big as life. Thought he was a ghost at first, I did, come to haint old Jim, who only tried to help him when his pa come back. Old Jim, who never told the missus bout all the times he sneaked out in the night to cat about. Slaves never have no luck—you remember that, child—it’ll save you lots a disappointment in this life. But no ghost ever blim-blammed like that, and so I knowed it was really him, his own self. That child could talk the hind leg off a donkey, he could. I kept quiet and let him run on, thinking mighty hard.

He had a gun, see. And people thought he was dead. Or was that just one a him and Tom Sawyer’s jokes again? It weren’t the first time white folks thought they was dead, though this’d be the first time a body had cared that Huck was gone, first time in his whole life. But there he was with a gun, a-chatterin and a-jammerin on. Was he a-hunting me? Hunting old Jim after he had his lark and made folks think he was dead?

Then he busts into my thoughts. Tells me to make up the fire and get breakfast, just like he owned me. That boy playing me, I thinks to myself, but I gots to know. Maybe he’s just a-hunting. So I axed him some questions, and found out he been there since the night he was killed. So whatever he’s a-playing at, he ain’t a-hunting old Jim. I tells him I’ll make a fire if he’ll hunt us up something for to cook on it.

I was expecting him to come back with some squirrel or some mud-turkles or such truck, or maybe a rabbit iffen I was lucky, and I hoped he had a knife with that gun, but I looked round for a sharp stone, just in case. When he come back, he come back with all kinds of stuff, a catfish and sugar and bacon and coffee and dishes, if that don’t beat all. I was set back something considerable, ‘cause I knew right away what it meant. Continue reading →

All Things with Humor

Richard Talbot

Fathers can show sons lots of things: how to buy your first house, how to replace a broken pane of glass, how to cut your meat when you are out in public, but how many fathers show their sons how to die?

In the summer of 1977, he told us that he had cancer. I remember the day when he arrived home with the news. Mom and I were sitting out on the front steps on a warm, sunny July afternoon. Mother sat next to me as I made tape recordings capturing the sounds of meadowlarks in the field across the street. Dad pulled into the driveway and got out of the car. He came up the walk smiling bravely as he approached. When he got four feet from her, he stopped. Shrugging his shoulders like a man who had just won second prize, he said, “It’s malignant.”

Thirty-five years of marriage afforded them such shorthand communication. Mom rose and fell into Dad’s arms. They said nothing more. She buried her face in the crook of his neck and cried softly. Meadowlarks warbled in the distance.

By this time, my father had been in AA for four years. It was his plan to take this way of living into whatever time he had left.

Earlier that day, when Doctor Duthoy had told Dad that he had cancer, my father asked, “Okay, how long have I got to live?”

“Paul,” the doctor replied, “we take these things one day at a time.”

That’s what Dad knew how to do. That’s the AA way and that’s exactly what he did.

Usually there are five stages that we go through when we learn that we have cancer: first, there’s denial, then bargaining, and then anger. This is followed by depression and finally, acceptance. Dad skipped the first four stages and went immediately to the acceptance.

For this, he was judged to be extraordinary by all who knew him.

There is a certain look, a demeanor that is carried by those who don’t have the cancer. Dad’s visitors fell into this approach when they spoke with him. Like undertakers they’d come, with saddened faces, with folded hands, and they would always say pretty much the same thing:

“Oh, Paul, we’ve just learned that you’re sick. We are so sorry.”

“Well, I’m not dead yet,” was his constant reply. “I think you’re the ones that look ill.”

He seemed awfully brave to those people. He was, in fact, not being brave at all. He had simply accepted his situation, and was going on, doing whatever he could do with the day that had been given to him. With humor, indefatigable humor, he would reply to his sympathizers, “Yeah, the doctor said he’d have to remove my testicles to stop the spread of the cancer. I told him that I wanted them replaced with pickled onions.”

Stunned confusion would wash across the faces of his listeners. He’d go on, “This way, whenever I go past a McDonald’s, I’ll get aroused.” (He didn’t use the word “aroused.)

His silly punch line would shatter the moment and into each other’s arms they would fall, laughing, seeing that all was not lost. Then they would talk. He made his listeners feel comfortable. They each thought he was magnificent.

Finding the Flow: Mark Twain, the River, and Me

While writing Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Twain had some trouble finding his flow. The manuscript was clearly important to him, and clearly troubling. His early mentions of it in letters are ecstatic — the writing was moving swiftly and clearly. But soon he hit snags. He ended up putting the manuscript away several times and writing three other books before it was finished. One of these books, Life on the Mississippi, has clear ties to Huck, but there are several significant scenes in his European travel “buddy” book, A Tramp Abroad, that also resonate strongly with his most famous novel. One of the funniest, and one of my favorites, involves crashing a raft.

Until this past Sunday, I had never really appreciated, except in a distant and intellectual way, Twain’s fascination with rivers. Even though I’ve been kayaking numerous times, and I’ve always had fun, I’ve never before tackled it with such a strong sense of my own mortality, the inscrutable flow of the current, and the exhilarating and hilarious terror of crashing. And now, frankly, I find myself even more puzzled by readings of the novel that focus on the idyll of the river and see the tension and the terror coming solely from the society’s intrusions on that peace.

A river, really, is a fucking scary place.

Those moments of calm, drifting slowly along with the current, fill you with the delusion that you understand the flow, that you’ve surrendered to it, that it will in some way take care of you.

What utter horseshit.

The river is a powerful and inexorable force, utterly oblivious to your puny self, and it is best that you never forget that — at least while you’re actually still in its reach. It is just as happy to have you smash into a boulder as it is to have you flow gently and peacefully in its lullaby.

Sunday was a lovely, lovely day. As I embarked on the annual Mother’s Day “Broads on the Broad River” trip, I remember thinking that it could not be more idyllic. The weather was perfect, sunny but not too hot, a constant breeze flowing; the company, of the best sort. I let myself go with the flow of the current, looking for the arrows in the water that mark the safe passages between the rocks in the rapids, floating with exhilaration when I hit them just right and shot through. And I laughed, too, when I missed the sweet spot and bumped over the rocks instead. The first small waterfall, pictured here, was easy this year, and I grew cocky as I made it through without dumping. The even smaller waterfall downriver, though — one that I wasn’t expecting — was another story.

Sunday was a lovely, lovely day. As I embarked on the annual Mother’s Day “Broads on the Broad River” trip, I remember thinking that it could not be more idyllic. The weather was perfect, sunny but not too hot, a constant breeze flowing; the company, of the best sort. I let myself go with the flow of the current, looking for the arrows in the water that mark the safe passages between the rocks in the rapids, floating with exhilaration when I hit them just right and shot through. And I laughed, too, when I missed the sweet spot and bumped over the rocks instead. The first small waterfall, pictured here, was easy this year, and I grew cocky as I made it through without dumping. The even smaller waterfall downriver, though — one that I wasn’t expecting — was another story.

Heavy rainfall had changed the river that I thought I remembered. Our group had gotten spread out, and I learned of the second waterfall only when I saw a distant friend ahead suddenly disappear. Her head reappeared downriver, and I marked the spot I thought I had seen her navigate the hazard.

Boy, was I wrong.

Only when I was on the crest did I realize how poorly I’d chosen my spot. Looming right in front of me with remarkable insouciance was a gigantic fucking boulder, lying crosswise, right in my path. I turned the kayak as fast as I could, to try to shoot the narrow space between the bottom of the fall and the rock, congratulating myself when I succeeded.

Dumb.

As soon as I shot out of the ironic shelter of that rock, the full force of the river hit the kayak broadside, throwing me and all of what Huck would call my “traps” into the current. I got my head above water, and ducked again just in time to keep from getting brained by my own overturned boat, maniacally spinning its own dance in the current.

Believe it or not, it wasn’t my life that passed before my eyes at that moment, it was this picture from Mark Twain’s A Tramp Abroad. (Twain scholars are truly weird people.) Here, the two friends sit blithely on their raft, with umbrellas to protect them from the sun, bathing their feet in the cooling water, and there is Sam, smoking away, like nothing will ever go wrong. But to me, now, it seems that there is a pensive gleam in his eyes, absent from his friend’s blank and vacuously smiling face.

As a child, Sam almost drowned in the Mississippi river numerous times. His brother Henry died on it, as did countless others he knew, and the slave trade was active up and down its waters. Mark Twain could have had no illusions about the ephemeral nature of the river’s idyll, whether the inevitable disruptions came from man or from the oblivious beast of the river itself. He had to be fully aware of the inevitability of the crash, of one’s helplessness in the current, of the hubris and strength with which we go against the current for a time or mistakenly believe we actually have control. Or peace.

In Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, the raft crash comes at a turning point in the novel. It is abrupt and terrifying, and it comes almost right after Huck has realized at last the magnitude of the crime he is committing by traveling with Jim. Further, he realizes at last that Jim has children of his own and an agenda of his own beyond helping this young white ragamuffin escape his father. But even then, Huck protects Jim from some slave catchers by telling them a lie, because Jim has praised him for being the only friend he has now, and for being “de on’y white genlman dat ever kep’ his promise to ole Jim” (124). But fog, the river, and a careless steamboat pilot result in a violent crash that separates them and changes the course of the novel.

In the complementary raft-crash scene of A Tramp Abroad, however, the moment is brief and fleeting — a minor but significant incident in the course of the novel. Here, in chapter nineteen, Twain’s narrator revels in his hubris and takes exuberant credit for the crash: Continue reading →