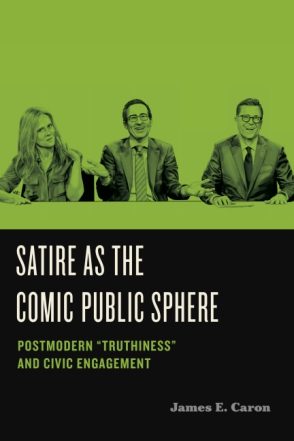

An interview with Jim Caron, author of Satire as the Comic Public Sphere: Postmodern “Truthiness” and Civic Engagement

Tell us about your start in humor studies. How and when did you begin pursuing it as a subject? who or what has influenced you as a scholar of humor?

My original topic for my dissertation was a folkloric look at the tall tale as a genre, but that morphed into the tall tale as a form in antebellum American comic writing and an influence on Mark Twain. So, in my academic career, I have always been interested in cultural artifacts that make people laugh.

However, the real turning point was being selected in 1989 for a National Endowment for the Humanities summer seminar on humor held at Berkeley and run by an anthropologist, Stanley Brandes. Those six weeks converted me to an interdisciplinary point of view. I spent more time in Kroeber Library (the anthropology collection) than any other library on the campus, mostly being fascinated by ritual clowns in traditional societies (my earlier folklore penchant had turned into an anthropological one). I’ve tried to maintain an interdisciplinary approach ever since.

.

Tell me about the genesis and creation of this project. What questions did you set out to answer, and how did your project develop to answer them?

The first impetus for the book came from submitting a proposal on satire to a projected collection of essays in the MLA teaching series. The proposal was rejected, but my interest in the topic had developed out of my Year’s Work reviews for Studies in American Humor because over the years I had tracked a growing set of publications on satire. Satire in the first decade of the twenty-first century was becoming a hot topic, which meant that for some time prior to writing the book I was immersed in the scholarly conversation about satire.

The second push came from a comment Judith Lee made about an introductory essay I had written for a special issue of StAH on postmodern satire. In the essay, I referred to satire as a special kind of comic speech act, and with her usual perspicacity, Judith said that that idea could be expanded. The foundation work I had done for the rejected proposal was then turned to use for the book, and the introductory essay on postmodern satire became the first draft of parts of the book.

I wanted to understand satire as a postmodern project in some of the artists that I had been faithfully watching on TV or in comedy specials. The entanglement of contemporary satire with the news was always a stimulus to my thinking. I also wanted to address the issues surrounding satire that I had zeroed in on when I wrote the proposal for the MLA collection: satire’s efficacy as a reform agent; satiric intent versus audience uptake; the importance of cultural context for understanding what the satirist intended and what the audience understood. I don’t see how one can tackle satire and not become enmeshed in these issues, and I use the examples in the book to work through them.

.

Your book—Satire as the Comic Public Sphere—develops a new approach to thinking about how satire, especially satire in the current media landscape, might operate. What do you hope that readers take from the book about how to understand satire?

The approach is new in part because I use speech act theory as a heuristic for contemporary examples of satire that play with the news, so I hope others find that tactic useful. The news as a focal point for some satire, however, points to the big claim in the book: that the best way to think about satire since the Enlightenment is to understand its connection to Jürgen Habermas’s concept, the public sphere. Satire parodies the public sphere and functions as its comic supplement. I think that framework makes sense, and I hope it persuades folks. Also, that framework enables understanding that satire functions as comic political speech, not political speech, which is how many scholars treat it. I suspect that there will be lots of resistance to that distinction, so I’ll be interested how it is processed in future scholarship.

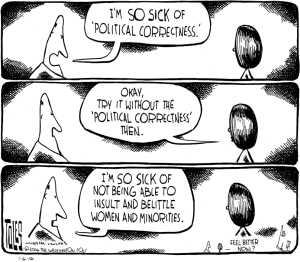

The idea of a “truthiness satire” in a postmodern aesthetic provides a way to think about the recent cultural moment in which people, in particular politicians, offer “alternative facts” as competition in the public sphere to evidence and empirical science. Some folks call the resulting situation “post-truth,” but that misunderstands what has happened, implying that no one is interested in the truth any more, or that it can’t be formulated in a meaningful way. That position is essentially a bastardization of postmodern skepticism, which questions transcendental claims for a Truth, but does not doubt that facts exist and should be marshalled in any public sphere debate. I refer to the dismissal of facts and evidence as the “anti-public sphere,” and ridiculing it is the job of truthiness satire. The book is meant to demonstrate the poetics of that ridicule. I also probe the legitimate limits of that ridicule: when does the symbolic violence of satire descend into mere rants or screeds?

Finally, the first part of the book offers an extended definition of satire that is meant to be useful for other cultures besides American and for other time periods besides now. I hope that readers understand the dual goals of the book: one general and not time-specific, the other very time specific.

.

What influence do you hope your book might have on conversations in humor studies? In other fields?

Of course, what I really want is to alter forever the course of scholarly thinking about satire [insert laughter here]. My hope is that the definition worked out in the first part of the book spurs some thinking about satire in general as well as satire’s function in what some call “the project of modernity,” which includes postmodernity.

For the book’s second part, I hope that my examinations of contemporary satirists like Stephen Colbert, Samantha Bee, and John Oliver are persuasive, that demonstrating the dynamic relationship among the discourse of the public sphere, satire as discourse of the comic public sphere, and truthiness as the discourse of the anti-public sphere shows just how and why satire has become so prominent and so important in recent times.

My approach centers on the aesthetics of satire as well as its communicative force in the public sphere, but satire as a cultural artifact has an appeal across disciplines, including rhetorical theory, communication theory, political science and sociology as well as cultural studies, so I hope the book can contribute to conversations in those fields as well as humor studies. That would be in keeping with my original interdisciplinary interest in what makes people laugh.

.

What trends do you see (or wish you saw) in humor studies? What do you hope for the future of the field?

As a contributing editor and associate editor of StAH for about fifteen years, what I’ve seen is a huge and still growing interest in comic artifacts of all sorts by a wide range of disciplines. That has been exciting to witness and to be a part of.

The scholarly trend has moved away from a focus on literary comic artifacts to other media, especially film, TV, and standup. Gender studies and ethnic studies have also been growing in their influence. Earlier historical periods are somewhat overshadowed by examinations of the now and the recent past. The internet beckons as a largely unexplored territory: we are still trying to get a handle on humorous or satiric memes, for example.

I see the study of cultural artifacts that make people laugh as a growth area (to use market terms) for some time to come. The variety of disciplines that are investigating those artifacts is wonderful, and I don’t envision that letting up. There are now several journals devoted exclusively to scholarship on comic artifacts, and I would not be surprised if others showed up in the future. Moreover, there is still much work that can be done in earlier historical periods. Just trying to keep up with recent artistic production will provide work for many scholars as we conduct our various kinds of research across disciplines.

What’s next for you?

I have another book project centered on satire, partly finished. (I seem to be stuck to satire as though it were a tar baby, though I am not complaining.) My research question: what did satire in the US look like before Mark Twain came along and altered everything? There is a long tradition in the scholarship on American humor in the nineteenth century that sees everything through the lens of Mark Twain, and I want to explore another perspective. Mark Twain is like Mount Rainier in Washington state, so dominating the terrain that is it difficult to escape his shadow.

My research in this project centers on the 1850s, and I am happy to say that there is more satire there than is usually discussed, a perfect example of what might still remain to explore in earlier historical contexts. The star of that book will be Sara Willis Parton and her persona Fanny Fern.

Want to hear more? Jim spoke on this panel for the New Book Talks with the AHSA that focused on New Books on Satire.

When Archie Met Sammy

I recently stumbled across a very entertaining and thought provoking list of 100 jokes that shaped modern comedy. The article is a fun read, and if you take the time to watch the video clips it is a good way to spend your entire weekend. As a scholar working on the intellectual history of the 1970s sitcom All in the Family, I was happy to see the show represented on the list. The joke representing the sitcom was from the classic episode Sammy’s Visit (originally aired February 19, 1972 on CBS), in which Sammy Davis Jr. forgets his briefcase in Archie Bunker’s (Carroll O’Connor) cab and comes to pick it up from his home on 704 Hauser St.

Archie: Now, no prejudice intended, but, you know, I always check with the Bible on these here things. I think that, I mean if God had meant for us to be together, he’d-a put us together. But look what he done. He put you over in Africa, and put the rest of us in all the white countries.

Sammy Davis Jr.: Well, he must’ve told ’em where we were, because somebody came and got us.

The joke managed to not only dress down Archie, but make a direct link between slavery and the continuing bigotry in America. The issue of Archie as a “lovable bigot”, a term used by Laura Z. Hobson to criticize him six months earlier in the New York Times, was also addressed head-on in the episode. The Bunker’s black neighbor Lionel Jefferson (Mike Evans) tries to explain Archie to their guest.

Lionel: But he’s not a bad guy, Mr. Davis, I mean, like, he’d never burn a cross on your lawn.

Sammy: No, but if he saw one burning, he’s liable to toast a marshmallow on it.

The episode is widely considered one of the most memorable sitcom episodes, and was ranked 13th on TV Guide’s 1997 list of the “100 Greatest TV Episodes of All Time”. Yet, the episode almost did not come to be. When Davis guested the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson in the spring of 1971, some months after the premiere of All in the Family, he lauded the new, controversial show and introduced the idea of himself guest starring on it. Norman Lear, the creator of the show, and John Rich, the director for the first four seasons, both agreed that wasn’t going to happen but appreciated the kind words and welcomed the promotion. Davis, however, kept pushing the idea. His manager tried to convince Lear and Rich, while Davis himself told the press a guest spot was in the works. Finally, Lear and Rich bowed to the inevitable and set about to find a way to incorporate the star into the show.

It was the writer Bill Dana who came up with the idea of Archie encountering Davis while moonlighting as a cab driver. Carroll O’Connor described the episode as a fun adventure but at the same time noted that it was atypical, being mostly “gags and jokes” and not “applicable” to anything broader the way All in the Family shows usually were. John Rich and Norman Lear, both pleased with the episode, also vowed never to do another celebrity guest episode. The show is great fun and ends with Davis kissing Archie on the cheek, as they are posing for a photograph. It is unclear whether Dana or Rich, who both claim credit, came up with that iconic television moment, which received what Rob Reiner called one of the longest laughs in history.

A final note to the story of when Archie met Sammy: Bill Dana, who wrote the show, was highly praised and perceived to be the favorite for an Emmy. As it happened, however, his agent’s secretary mistakenly sent the necessary paperwork to the Writer’s Guild instead of the Television Academy. Without even receiving a nomination, Dana watched as the show took home ten awards, including Outstanding Directing for Sammy’s Visit. There is a humorous side to such a silly mistake costing Dana, a comedy legend in his own right, an Emmy, though I doubt he saw it that way.

“There you go again”: Humor in Presidential Debates

In early August, Fox News and Facebook organized the most watched primary debate ever, in Cleveland, Ohio, where 17 Republican presidential hopefuls gathered in two debates in hope of emerging as the star of the field. The pundits are still out on who exactly ”won” the debate, curiously there seems to be something of a correlation between the ideology of the pundit and whom they declare the winner. Among much post-debate think-pieces, media bickering, and inappropriate comments by Donald Trump, the perhaps best, and certainly funniest, piece was a bit by Funny or Die featuring kids reenacting the debate.

Since presidential debates became a staple of the election season following the 1976 debate between Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter, they have been the source of much comedy fodder. Saturday Night Live has over the years, since 1976, provided such gems as this Bush-Clinton-Perot debate, focused on Arkansas as backwater, this Gore-Bush sketch, Will Ferrell as Bush became a long-time favorite, and the instant classics of Tina Fey as Sarah Palin, like this. The Funny and Die bit, however, highlights the inherent humor in the actual debates. For while it might be more fun to just catch Dave Letterman’s recap of the debates than actually watching hours of political posturing, even the politicians drop some funny lines.

Historically, the presidential debates debuted with the 1960 Kennedy-Nixon debates, but as both Lyndon Johnson and Nixon then avoided debates in their 1964, 1968 and 1972 runs respectively it wasn’t until the 1976 campaign they returned. Since then they have been a crucial part of any election cycle, including the primary cycles. The humor in presidential debates consists mainly of inadvertent gaffes or advertent zingers. The perhaps foremost example of the first category dates back to the 1976 debate where incumbent president Gerald Ford claimed there was no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe. Max Frankel of the New York Times, serving on the panel of moderators, can barely conceal his grin as he in disbelief asks if the president is actually saying Eastern Europe is not within the Soviet sphere of influence. The blunder by Ford enhanced the impression of him as somewhat dim, and was used to great extent by the Carter campaign. A more recent example of a humorous debate mistake would be Rick Perry’s inability, in a Republican primary debate in 2012, to remember the third government agency he would do away with if elected to the White House. Falling back on his Texan charm Perry tried to brush it aside with a nonchalant “oops”, which only made the whole exchange sillier. Speaking of silly, Mitt Romney’s attempt at humor when proposing to cut funding to PBS, saying that he likes Big Bird (of Sesame Street fame) but would still axe it, also misfired as it gave more than ample ammunition to editorial cartoonists, meme-ers, and comedians all over the country.

When the candidates in the debates are consciously humorous it is more often by a joke on the opponents account, a zinger. These certainly seem to have decreased in recent years, and the defining debate zinger remains one from 1988. Irritated of continuing criticism of his inexperience, vice presidential candidate Dan Quayle in the 1988 vice presidential debate explained that he had as much experience as John F. Kennedy had when he sought the presidency in 1960. His opponent, long-serving Texan Senator Lloyd Bentsen, saw his chance for a put down and clearly took pleasure in delivering the zinger of the century. “I served with Jack Kennedy, I knew Jack Kennedy, Jack Kennedy was a friend of mine. Senator, you’re no Jack Kennedy”, Bentsen replied with a smile hardly hidden. Increasing the comedy, Quayle’s face dropped to the floor and clearly hurt he said the comment was uncalled for. Bentsen’s comment was immediately viewed as bold; if he wasn’t crossing a line he was at least approaching that line. The risk with crossing the line is that you come off as mean, which is a reason most of the best zingers hail from vice presidential debates – the designated hatchet men. Back in 1976 Republican vice presidential candidate Bob Dole showed off a sharp wit, repeatedly making cracks about his opponent Walter Mondale and presidential candidate Jimmy Carter. Viewers found Dole lacking in seriousness and coming off as a wisecracker, making him unappealing.

Ross Perot, debating with Bush and Clinton in 1992, similarly highlighted his comedic chops with repeated jokes and zingers. As a candidate from outside the political establishment the strategy was risky, it was crucial for him to appear presidential, and ultimately a failure. “It’s nice that someone has some humor and lightens things up, but now it seems like every opportunity he had to speak he had a quick one-liner”, was the verdict of one focus group. The risk of not appearing responsible and mature enough for the White House actually led the naturally witty John F. Kennedy to tone down his humor in the 1960 debates. As Kennedy was struggling with the perception of him as too young and his reputation as witty aldready widely appreciated the strategy seemed good. Still, sense of humor remains a key factor for voters in determining the character of a candidate, not to mention likability. Moreover, a well delivered zinger or joke is almost certain to reach a larger audience by making it to post-debate coverage – especially on television and today YouTube. To find a balance is vital, yet difficult.

The only president who ever truly mastered humor in presidential debates was Ronald Reagan. “The Great Communicator” had a good sense of humor and a background in delivering lines and presenting himself appealingly. In 1980, as Jimmy Carter laid out his case against Reagan, he smiled confidently and good-naturedly said “there you go again” before defending himself. The almost laughing Reagan uttering the “there you go again” is as close to iconic as presidential debate moments get. It was a part of Reagan’s debate strategy to throw Carter off with humor and smiles. When facing Mondale four years later, Reagan delivered another classic when he ironically answered a question by promising not to make his opponents age an issue of the campaign – his own age was of course what had been questioned in recent weeks. The joke not only drew large laughs from the crowd but from the moderator and Mondale, again highlighting Reagan’s affable personality. By mixing self-deprecation with irony and a message, Reagan showed off presidential debate humor at its best; if even the opponent is getting a good laugh you know you’re doing something right. Apropos irony, we still have some twenty debates in the 2016 cycle to look forward to!

For more commentary on the 2016 elections, check out the interdisciplinary election podcast Campaign Context at www.campaigncontext.wordpress.com.

John Oliver, FIFA, American Humor, and Topic Sentences

John Oliver got rid of Sepp Blatter. That would be a bold statement if I cared at all about Sepp Blatter or FIFA. I do not. I do care, however, about John Oliver, my favorite funny person from Great Britain (currently; it is a long list). More importantly, for this venue, is the contribution that John Oliver with his work on Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (HBO) is making to American humor. As one who has been distraught over the loss of The Colbert Report and the impending departure of Jon Stewart from The Daily Show, I have been worried that we were facing the end of a golden age in American television political and social satire. I think it will last a bit longer, and I am sure that John Oliver is key to its future.

John Oliver got rid of Sepp Blatter. That would be a bold statement if I cared at all about Sepp Blatter or FIFA. I do not. I do care, however, about John Oliver, my favorite funny person from Great Britain (currently; it is a long list). More importantly, for this venue, is the contribution that John Oliver with his work on Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (HBO) is making to American humor. As one who has been distraught over the loss of The Colbert Report and the impending departure of Jon Stewart from The Daily Show, I have been worried that we were facing the end of a golden age in American television political and social satire. I think it will last a bit longer, and I am sure that John Oliver is key to its future.

The Nightly Show with Larry Wilmore is solid, and Trevor Noah may prove to reinvigorate the Daily Show, so my worries may be overblown. It is Last Week Tonight, however, that holds the most promise. Quite simply, it transforms the basic formula codified by The Daily Show under Jon Stewart (and applied to a specific parodic context by Colbert) and makes it decidedly more argumentative. Last Week Tonight is thesis-driven humor, which marks a dramatic shift in ambition, or, perhaps, confidence. In either case, Oliver will not admit it.

Oliver is nonetheless catching fire. On a recent appearance on CBS This Morning , Charlie Rose asked one question that seemed clear and concise (if you can believe it): “What is the intent of this ‘dumb’ show?” (Oliver had already called it “dumb” based on the introductory clips).

“Just to make people laugh.” OK, John, you get a pass since this is the standard answer for any such discussion of humor. Why a duck? Because ducks are funny, that’s why. But you are lying.

Oliver’s self-deprecation notwithstanding, the fact is that no one in American television has ever put together satirically charged arguments in segments ranging from 12 to 20 minutes (easily 2 to 4 times as long as standard Daily Show bits) that are focused on one issue with such depth and humor. Never. There are easier ways to make people laugh.

In the interview, Oliver would not assert a more elaborate purpose and underplayed any major role for satire itself. As to whether satire served a deeper purpose in his work, he simply said, “I have no idea. Ideally, satire would do no better than anyone.” He went on to explain the show’s long form, weekly approach: “It’s some slow cooking, what we do.”

Yes, slow cooking. It took a year to get Sepp Blatter. That is the pace of satire. C’mon, John, admit it.

To begin a closer look at the Last Week Tonight formula, let’s stick with Blatter and the two episodes that most directly skewer FIFA, the first of which aired on 8 June 2014 and the second on 1 June 2015. A brief look at these two episodes should provide a good indication of the power of Oliver’s thesis-driven comedy and the potential of long-form television satire. Both episodes feature FIFA as the main topic, and each segment runs just over 13 minutes. Here are links to each:

The key to Oliver’s approach could be understood best, perhaps, by considering it as a model for clear, argumentative writing. In fact, I urge all freshman composition instructors in the nation to drop all textbooks and simply use Last Week Tonight to teach the modes of argumentative writing. Let’s consider the most basic element of building effective arguments: Write clear and concise topic sentences. Note the few examples below:

–“FIFA is a comically grotesque organization.” (8 June 2014).

–“There is a certain irony in FIFA setting up any kind of justice system given the scandals that have dogged it over the years.” (8 June 2014).

–“The problem is: all the arrests in the world are going to change nothing as long as Blatter is still there.” (1 June 2015)

–“When your rainy day fund is so big that you’ve got to check it for swimming cartoon ducks, you might not be a non-profit anymore.” (8 June 2014)

–“Peanut butter and jelly are supposed to go together; FIFA and bribery should go together like peanut butter and a child with a deadly nut allergy.” (8 June 2014)

–“That is perfect because hotel sheets are very much like FIFA officials; they really should be clean, but they are actually unspeakably filthy, and deep down everybody knows that.” (1 June 2015)

Note the clarity of the argumentative position in each statement above. They assert positions, all followed by multiple levels of support within the show (follow the links). That, dear readers, is how you build good essays! It is also how to build fresh, ambitious humor.

To be or not to be Charlie

Teresa Prados-Torreira

To be or not to be Charlie, that has been the question many academics and commentators have pondered for the last two weeks. At first glance it seems obvious that the answer to this dilemma should be a wholehearted affirmation of the need to stand in solidarity with the French magazine, with the murdered cartoonists, and in support of free speech. But the content of Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons, their irreverent depiction of Mohammed and Muslims, have resulted in a cascade of critical essays online and elsewhere.

“Why would anyone want to be identified with a racist organization such as Charlie Hebdo? ” wonders a colleague. Many observers have pointed out that the provocative images of Muslims as hook-nosed, dark-complexioned, sinister people with criminal intentions echo the anti-Semitic cartoons of yesteryear, and nurture the idea that Muslims are alien undesirables.

“But why are Muslims so thin skinned when it comes to religion?” complains another colleague.

For most Christians living in the Western world religion is not the defining factor of our identity. The fact that I was raised Catholic and still feel a cultural connection to Catholicism hardly affects my everyday life: Neither my social, political or professional life are determined by my Catholic upbringing. That is definitely different in the case of European Muslims who find themselves stigmatized, distrusted and powerless in their own countries. For faithful Muslims in France, religion is not a colorful ritual, something warm and fuzzy that is to be evoked during the holidays because it brings families together. Their religious background is at the crux of who they are and how they treated.

Joker Poe, Part 5: The Jingle Man

“Ha! ha! ha! – he! he! – a very good joke indeed – an excellent jest. We will have many a rich laugh about it at the palazzo – he! he! he! – over our wine – he! he! he!”

These giggling words are among the last uttered by Fortunato, the rather unfortunate victim of a deadly practical joke in Edgar Allan Poe’s memorable tale, “The Cask of Amontillado.” In that short story, the narrator Montresor directly discloses neither the “thousand injuries” he’d received from Fortunato nor the final “insult” that led him to vow revenge, but he does present his plan as the solution to a puzzle: “I must punish, but punish with impunity. A wrong is unredressed when retribution overtakes its redresser. It is equally unredressed when the avenger fails to make himself felt as such to him who has done the wrong.” In other words, Montresor must take his revenge upon Fortunato in such a way that the victim knows all, while the perpetrator is in no danger of being caught. Montresor’s elaborate charade with the wine, the catacombs, the trowel, and the stones reveals his ingenious solution. As is well known, Poe himself took great pride in his analytical, puzzle-solving abilities, and Montresor’s plot reveals a certain gift for ratiocination that Poe valued. At the final moment, after Fortunato has been almost completely immured, Montresor calls his name. “There came forth in return only a jingling of the bells.” And thus is buried another “jingle man.”

In this series of posts, “Joker Poe,” I have argued that Poe is best viewed as a literary prankster, a practical joker who employed his prodigious intellect, his acute awareness of the marketplace, and his gifts for writing to satirize the culture and society of his era. In a sense, his own readers are suckered in by his tales, poems, and criticism, while Poe himself is likely having a chuckle at their expense. Poe was the great theorist of “Diddling,” which he considered as one of the exact sciences, and he insisted that no diddle—a swindle, confidence-game, or prank—is complete without a “grin,” but only one that the diddler himself wears, seen by no one else. Poe’s propensity for diddling extended to his literary career, which can be seen not only in those works which are clearly hoaxes, but also in his poetry, his tales, and his criticism. Not surprisingly, Poe made enemies, some of whom have not been so sanguine in accepting the thousand injuries and uncounted insults visited upon them by the grinning diddler.

After Rufus Griswold, whose calumnious portrait of Poe in an obituary caused outrage but likely led to Poe’s eventual enshrinement in a popular-cultural canon, perhaps the most famous of the fabled detractors of Poe during his lifetime was also America’s leading public intellectual, Ralph Waldo Emerson. The phrase “jingle man” is well known in American literary studies, not to mention infamous in Poe Studies, as Emerson’s dismissive appraisal of Poe. That the Sage of Concord might dislike Poe is not surprising, since Poe was probably as ardent an opponent of Emersonian transcendentalism as anyone other than Herman Melville, and Poe’s invectives were especially caustic when it came to the Boston literati, many of whom appeared to be well-nigh slavishly devoted to Emerson’s thought. Poe also criticized Emerson himself as belonging to “class of gentlemen with whom we have no patience whatever—the mystics for mysticism’s sake.” In a follow-up to Poe’s eccentric little series on “Autography,” in which he proposed to analyze the handwriting of famous authors, Poe humorously suggested that “[t]he best answer to his twaddle is cui bono? […] to whom is it a benefit? If not to Mr. Emerson individually, then surely to no man living.”

Joker Poe, Part 3: Horrific Humor

In my previous entries in this series, I have discussed the ways in which Edgar Allan Poe might best be thought of as a literary prankster, a “diddler” or a practical joker, who delighted in “putting one over” on his readers. This flies in the face of the wildly popular depiction of the nineteenth-century poet and littérateur. To his legions of fans and to the multitudes of merchants making commercial hay (and no small amount of money) off of Poe’s mythic image, Poe remains best known and best loved today as dark, brooding, alcoholic, madman-genius. However, to the great disappointment of my own students, all biographical evidence suggests that this image is largely false. Yes, Poe had his occasional problems with the bottle, although in this he was not all that far from the norm in his besotted epoch, and yes, he wrote some stories about madness, mayhem, mystery, and mortality, although he wrote far more burlesques, hoaxes, satires, and spoofs. Above all, Poe was a canny magazinist, an astute judge of the appetites of the reading public, and he used his own literary talents and business acumen to give the people what they wanted.

One of the things that readers desperately wanted, as Poe knew better than most, was a shock, especially in the form of tales combining elements of the bizarre, extravagant, terrifying, and weird. If Poe is best remembered today for his tales of terror, it is in part because he recognized that such tales would be the most popular in his own time. For example, after one publisher objected to the gruesomeness or bad taste of “Berenice” (a rather disturbing tale, it’s true, but well worth the read!), Poe explained that “to be appreciated, you must be read,” and he pointed out that such stories are “invariably sought after with avidity.” What kind of stories are so popular? “The history of all Magazines shows plainly that those which have attained celebrity were indebted for it to articles” whose nature consisted of the following: “the ludicrous heightened into the grotesque: the fearful coloured into the horrible: the witty exaggerated into the burlesque: the singular wrought out into the strange and mystical.” In other words, Poe asserts, excessive, over-the-top stories are what the people demand. So, again, if Poe became a master of horror, it is because Poe knew that horror sells.

How does this relate to my argument that Poe is best viewed as a literary practical joker? Poe’s burlesques, hoaxes, bizarreries, and practical jokes are obviously examples of his perverse sense of humor. But what about those stories that are “clearly” meant to be read as works of horror, mystery, or suspense? It is not for nothing that Poe is widely considered a master of Gothic fiction, right? (My use of the scare-quotes is an obvious giveaway, indicating my skepticism over whether any of Poe’s work could “clearly” be so described.) I would assert that even Poe’s apparently Gothic tales of terror are, on one level or another, also examples of satire, humor, or hoaxing. That is, even in his apparently serious fiction, Poe’s impish, satirical, and critical attitude prevails. This is not to say that we need to re-categorize Poe’s tales of terror as comical pieces, but it is to suggest that the prankster’s spirit infuses all of Poe’s work. As an example, I would like to look at “The Fall of the House of Usher,” one of Poe’s most famous and celebrated works of Gothic horror. Notwithstanding its gloomy atmosphere, mysterious characters, and horrifying climax, the story of Roderick and Madeline Usher’s frightening downfall is thoroughly suffused with playful humor. Continue reading →

Top 4 Reasons to Teach Sherman Alexie

“Humor was an antiseptic that cleaned the deepest of personal wounds.” – Sherman Alexie, The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven

When I was a college freshman, a beloved English professor first introduced me to author Sherman Alexie. I have had the opportunity to pay it forward and teach Sherman Alexie (most notably his novel Flight) to freshman students for the past 6 years. Here are my top 4 reasons you should be doing the same.

1. He’s funny.

We teach in a modern, text-filled world where laughing out loud and rolling on the floor laughing are common phrases that now appear in our inboxes, piles of essays to grade, and classroom discussions. While this reliance on slang always reminds me to make a note, ‘AVOID SLANG’ in my syllabus, I am pleased to present an author who creates a safe space for readers to ‘lol’ and/or ‘rotfl’ and aim to generate a similar environment in my college classroom.

I usually introduce Alexie with a brief biography and a lot of excitement – I affectionately create an ‘S.A. Opening Day’ complete with an interactive Prezi on the Spokane/Coeur d’Alene Indian from Wellpinit, Washington. In recent years, I have begun our discussions with clips from Time’s 10 Questions Series and Big Think’s Interview with Sherman Alexie below. While these videos help to promote different works, they also provide a context for young readers to see and hear from the author directly. When I ask for first impressions, students comment on Alexie’s passion about subjects like banned books, Native American history, and novel writing. They applaud his frankness and his ability to tell it like it is. Mostly, though, they talk about his humor. They continue to do so while reading his novel Flight.

2. He’s seriously funny.

In the midst of reading, students always exchange tales of laughter – they dog-ear pages to later share with classmates. Interestingly enough, students also inquire about another side of Alexie’s humor. They begin to question if they should be laughing at some of the outrageous stereotypes, politically incorrect statements, and explicit innuendos – and they dog-ear these pages as well. While they may not be aware of it, Alexie helps students become more active readers and critical thinkers. He helps them to formulate differences between types of humor such as slapstick, dark humor, and satire. Through satirical portrayals, he presents serious issues many of my students face on a daily basis such as alienation, peer pressure, and stereotyping.

In class, students create an ongoing list of ‘seriously funny moments’ from the novel, and explore these instances in their final papers. They use humor as a tool to talk about thoughtful social and cultural issues, an idea garnered from the pages of Alexie’s own work. For their final essays, they answer one or more of the following questions in an effort to explore, expand upon, and showcase their understanding of humor’s impact on society: How do humorists (like Sherman Alexie) use humor to get us to think about the world?; How does the type of humor in Alexie’s work impact, change, progress, and/or regress our worldview?; How, if at all, might this type of humor used in Alexie’s work help us to prioritize our values?; and How, if at all, might the instances of humor in Alexie’s work help us to change American society?

3. His writing is accessible.

I am a big proponent of challenging my students’ abilities – their writing skills, reading comprehension, and critical thinking – in my freshman English course. On the other hand, students often have a different agenda. With such a varied student population with an even more diverse set of skills in each classroom, I find their motivation to learn on a broader spectrum than ever before. Alexie’s writing, through culture references, simple sentence structure, and descriptive language, connects his characters’ thoughts to his readers’ world. Often, lofty diction and complicated sentence construction can alienate young readers. After a semester of trying to challenge their comprehension and deciphering skills, Alexie is a breath of fresh, easy air. Through his writing, he illustrates that language should promote critical thinking about sober, cultural issues plaguing the current American landscape.

His writing is also a great model for students. I often ask them to write and speak what they know – to avoid using the right-click feature found on their computers that allows them to replace their vocabulary with less familiar, obtuse words. I want them to focus on effectively communicating their ideas onto the page, and Alexie acts as a bestselling example.

4. He helps develop empathy in readers.

Call it what you will. Whether it is social consciousness, social awareness, or social understanding, Sherman Alexie has a true gift of facilitating empathy for other human experiences. As my freshman students study, humor, specifically the kind utilized by Alexie, helps to create a shared experience. These shared experiences produce stories, which are often told in the classroom, and build understanding and tolerance across different cultural boundaries. Alexie explores Native American stereotypes – the drunken Indian, the noble savage – and shows their harmful effects on the psyches of young men growing up both on and away from the reservation. He discusses cultural boundaries and often shatters preconceived notions of Native Americans, all in an effort not to acquire sympathy, but instead to illustrate the destructive force of willful ignorance. True understanding of another’s pain, isolation, and successes combats this deliberate cultural obliviousness. His interview with Bill Moyers, “Sherman Alexie on Living Outside Borders” is a poignant example for this discussion.

We spend a great deal of time on historical context as the novel presents it. History is important to Alexie, and it is often the place to begin a discussion on empathy. We discuss historical injustices, legendary battles, and prominent figures, such as Jackson’s dismissal of the Supreme Court ruling for the Cherokee nation, leading to the Trail of Tears, Custer’s Last Stand, and Crazy Horse. My young students grapple with an historical understanding of these cultural experiences, and in weekly reflections, they often discuss with their own values, ignorance, and biases, senses and stories of personal betrayal, alienation, and cultural seclusion. Considering different histories and perspectives aids in the development of a more informed, empathetic, and socially conscious society. While habitually reliant on bland, disingenuous phraseology regarding their emotions, twenty-first century readers learn through Alexie’s affirmation that true emotions and deep, sincere empathy builds lasting, valuable human connections.

© 2014 Tara Friedman

Tara E. Friedman currently teaches English and Professional Writing at Widener University in the outskirts of Philadelphia. She is ABD at Indiana University of Pennsylvania and hopes to complete her dissertation on female resistance and agency in select late nineteenth and twentieth century American novels and graduate in 2014 with her PhD in Literature and Criticism. While she has presented on critical thinking and writing center theory and pedagogy at the CCCC, her other research interests include nineteenth century British novels, the sixties in America, and American humor.