Ethical Conundrums: Gerhard Reinke’s Wanderlust and Las Hurdes

You probably never saw it, but it was a funny show with something and nothing to say. Back in 2003, Jimmy Kimmel’s Jackhole Productions produced six episodes of a show for Comedy Central called Gerhard Reinke’s Wanderlust. Each week, its fictional German host (played by American Adam Gardner) toured some part of the world – usually some part of the third world. Gerhard Reinke was a hapless traveler. He succumbed to some sort of travel-related malady in nearly every show – from bugbites to embarrassing erections.

When a situation demanded caution, he was gullible. Where compassion would have been appropriate, he was shrewd. After cheerily explaining that, “Bolivia’s economic crisis makes it one of the cheapest places in the world!,” he rather cruelly haggles over seemingly low-value currency with a presumably poor woman selling a llama fetus in La Paz’s “witch’s market.”

Though his travel skills were severely lacking, Reinke fared little better as a television host. On the easier side of the show’s humor, his thick German accent led to some cheap laughs when he visited “Wenice Beach” California. But his challenged hosting skills could demonstrate a sharper satirical edge as well. As evidenced in his celebration of Bolivia’s troubled economy, his narration rarely matched the tone demanded of a situation. While Gerhard cheerily described the miseries caused by international economic inequality, he was deadly serious when dealing with insubstantial maladies or undertaking any of his projects (like searching for Bigfoot or writing erotic fiction). Fundamentally, these moments of tonal contradiction evidenced a self-centeredness that appears to trouble the ethical positions of both the tourist and media consumer in a global economy. At the same time, it is a comedy and as such it is better at critiquing than offering solutions.

In this way, it is reminiscent of Luis Buñuel’s 1933 film Las Hurdes: Tierra Sin Pan (English: Land Without Bread). This film, also a mockumentary travelogue, offers its audience a view of an economically disadvantaged peasants living in the Hurdes region of Spain. While not as obviously comic as Wanderlust, Buñuel’s humor relies on a similar tonal mismatch. The narrator of this film remains disinterested and at times even amused as he describes and comments on the terrible conditions of the film’s subjects. Gerhard’s relationship to his audience is a bit more complicated. Unlike the disembodied “voice-of-God” narrator of Las Hurdes, Gerhard is a transparently flawed host. Laughing at Buñuel’s narrator feels somewhat like laughing at myself. The laughter directed at Reinke is less reflexive – it is directed at the over-confident “German” doofus. Still, laughing at Gerhard is not entirely unproductive. Although he does not implicate the viewer as directly as does Las Hurdes‘ narrator, we still must accept Reinke’s position as viewer surrogate in our relationship to this media text. And unlike in Buñuel’s film, we here see the figure of the tourist in some of its worst excesses. This kind of misery-tourism might be subtly suggested in Las Hurdes, but it is a major and explicit theme in Gerhard Reinke’s Wanderlust.

In perhaps its most obviously comic moment, Las Hurdes shows a goat scaling a rocky cliff. “One eats goat meat only when one of the animals is killed accidentally,” explains the narrator. “This happens sometimes when the hills are steep and there are loose stones on the footpath.” A puff of smoke billows in from offscreen and the goat falls. The narrator has lied to us. The goat did not trip – it was shot. While the whole film seems to ask what the viewer’s responsibility might be towards disadvantaged Others, this moment suspends those questions to ask more fundamentally what and how we actually know about the people and things we witness from the other side of the screen.

Similarly, though with more broadly comic strokes, Wanderlust mixes a heaping dose of falsity into its documentary explorations. Every episode devolves into some kind of fictional narrative as Gerhard joins a Marxist revolutionary group or struggles with an affliction known as “pee shyness.” So although a good part of both texts ask us to think about our relationship to other human beings, these moments undercut their moral imperative by asking how we can even know the experiences of others in these distant places. There seems to be on the one hand an imperative to act based on the documentary evidence of human suffering. But there is also a more radical proposition that we can’t trust texts like the ones we are watching, which undercuts the moral certainty of the first proposition.

So which is the more powerful argument? Neither Las Hurdes‘s narrator nor Gerhard Reinke (or Luis Buñuel or Josh Gardner) will tell us. Despite the apparent intended message of Las Hurdes, it offers a message of resignation in the face of suffering. While the concern with other humans seems the more ethically defensible position, the proposition that these media themselves are untrustworthy denies such neat moralism. Disturbingly, the warnings against being overly trusting of such appeals seems to be the more powerful message here. So don’t worry too much about the Hurdes or the poor woman selling the llama fetus: they might as well be fictional.

In the Archives: Edgar Allan Faux (1877 then 1845)

They say humor is based on timing. Yes, as is everything else. Ask Elisha Gray about telephone patents. I was plugging along, working on a piece about the comedian Dana Gould, and still figuring out when I would finish writing about Mark Twain and the German language, when an article in my local newspaper caught my attention:

“Dead Poets Society founder visits 300th grave”

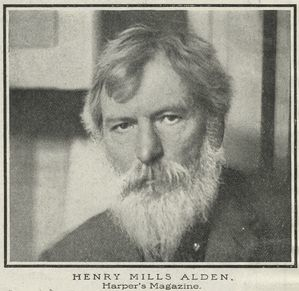

The fact that there’s an actual Dead Poets Society prompts visions of Ethan Hawkes’s teeth and an involuntary desire to kill Robert Sean Leonard. Swallowing my bile I learned that the current founder, Walter Skold of Freeport (Maine), has visited the gravesites of 300 poets “ahead of this weekend’s fourth annual Dead Poets Remembrance Day.”

What is “Dead Poets Remembrance Day”? Apparently, “with the help of 13 current and past state poets laureate,” Skold was able to dedicate October 7—“the day that Edgar Allan Poe died and James Whitcomb Riley was born—to heightening public awareness of the art of poetry.

The article posted October 5. That was Saturday. Making the actual memorial day a Monday. Today. My day to submit. So in honor of dead poets everywhere (and as one who writes the occasional verse and considers the artform dead, and therefore all practitioners the undead) let us examine the two poets tied to this day. What the article does not share is an appreciation for not just the day, but the year. On October 7, 1849, as Edgar Allan Poe lay dying of possibly drunken Rabies in a Baltimore medical college, James Whitcomb Riley was borning in Greenfield, Indiana.

In the Archives: Sprachen Studies (1917 then 1897)

So last month, when I recounted the recent Mark Twain Quadrennial, in Elmira, New York, I did not lie to you when I said my last name was a rarity outside of Brazil. But I might’ve misled. I’m not Hispanic. The name, phonetically confusing no matter the accent, originates from a very localized area in the Catholic part of Germany. Before social media made rabble of us all, my immediate network of genetic cognates stretched the length and width of America, but number well under forty (out of 313.9 million Americans without my last name). Once humans began twittering, a search for my surname generates hundreds of Andrés, Rafaels, Guilhermes, Edleides, and Gabriels. All of them write in Portuguese, and the best I can figure populated the Southern Hemisphere in the nineteenth century. Their ancestors did anyway. My ancestors begin with my great-grandfather, his wife, and my grandfather, barely a toddler in 1920, leaving Köln after fighting Americans for the Kaiser in the Great War. He set up his own machine shop outside of Boston, and began a tradition of not passing on family history to the next generation, and so in turn we know very little but apocrypha.

But apocrypha is a start. While we seek a connection with our distant Vaterland, all of us—North and South American—still sit under the shadow of a later holocaust with greater ethical concerns than the mobilized imperial reaction to the assassination of Franz Ferdinand in June 1914. Thankfully, none of us bear any of the guilt, even if there’s always the cinematic suspicion. For those of you too young to remember, Zie Germans were fun adversaries in popular media long after World War II and despite the atrocities committed on their own citizens. Hollywood couldn’t quit them as antagonists until 9/11 made clandestine sleeper cell guerrilla terrorism all the rage. Islamic extremists make for good long-form television, but not epic two-hour cinema. Meanwhile the pomp and circumstance of Nazi regalia still seems a popular attraction. And if the uniform gets a little thread-bare, Hollywood’s costume designers can go back a score and break out the Kaiser’s pointy helmets and Red Baron pilot goggles.

In the Archives: Thomas Nast and Santa Claus (1862-1890)

I can remember my first scholarly thought. Well, I should say that I can visualize the context of my first scholarly thought. Like a Polaroid of a younger me looking through a View-Master: I know that I saw something, and how, but can’t remember what.

I can almost replicate the place from memory, but will never replicate the time. Heraclitus, who was smarter than the average Greek, once wrote fragmentedly, “You cannot step into the same river, for other waters and yet others go ever flowing on.” True, but the Greeks widely preached the maxim to “Know Thyself,” and I remember helping my grandfather once, and being rewarded with a copy of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

To be precise it was The Annotated Huckleberry Finn, edited by Michael Patrick Hearn, copyright 1981 by Clarkson N. Potter, republished by Norton & Company. When my grandfather gave me the book it was still new scholarship, and I was no scholar, but the text fascinated me. Densely illustrated, the Potter edition uses marginalia to communicate the context of both the novel and Hearn’s Introduction like an analogue prototype for the internet. I was a babe in the woods, looking through the first book I ever owned that did not involve talking animals or a young sleuth by the name of Encyclopedia Brown. I was proud that someone thought me ready for such an impressive text, but make no mistake, the pictures helped. As a child I was not a strong reader, but I was wildly artistic. And the first page I opened had a caricature of two men, in nightgowns, with nineteenth-century facial hair, collecting clocks.

I don’t think I can reproduce it here for legal purposes, but Roman numeral lvi (56) of the Norton edition will show you the two figures identified as the authors George W. Cable and Mark Twain, drawn by Thomas Nast, on Thanksgiving, 1884.

There was no other description behind the cause of their act, collecting clocks at five before midnight, besides: “The two spent Thanksgiving at Thomas Nast’s home in Morristown, New Jersey.” I cannot fault Hearn’s lack of insight, because it sparked the first real academic inquiry in my young mind: What the hell is going on?

I can tell you that later I learned:

On Thanksgiving Eve the readers were in Morristown, New Jersey, where they were entertained by Thomas Nast. The cartoonist prepared a quiet supper for them and they remained overnight in the Nast home. They were to leave next morning by an early train, and Mrs. Nast had agreed to see that they were up in due season. When she woke next morning there seemed a strange silence in the house and she grew suspicious. Going to the servants’ room, she found them sleeping soundly. The alarm-clock in the back hall had stopped at about the hour the guests retired. The studio clock was also found stopped; in fact, every timepiece on the premises had retired from business. Clemens had found that the clocks interfered with his getting to sleep, and he had quieted them regardless of early trains and reading engagements. On being accused of duplicity he said: “Well, those clocks were all overworked, anyway. They will feel much better for a night’s rest.” A few days later Nast sent him a caricature drawing—a picture which showed Mark Twain getting rid of the offending clocks. (Mark Twain, a Biography, vol. II, part 1, 188)

But all this postdates my first academic thought. Before I knew Huck, Jim, the Mississippi River, or the author who sent them down it. I saw a picture and knew the name of the man who drew it. Thomas Nast. I remember I wanted to know more, and now I can share some of it with you, in context.

In the Archives: Artemus Ward’s Panorama (1869)

I hate word games. I suffer Scrabble, abhor Boggle, and you’ll never catch me cross words. I prefer etymology, and catch myself wondering about the subtleties of language the way you might answer, “I’ll take New York Times crossword for $200, __”. Consider an example: in English the first ordinal number might also serve as the numerical superlative. Given the ordinal role shows rank, or position, and the “-st” ending it shares with the hyperbolic “most” or “best,” I am comfortable maintaining that while “first” may be subject to the same controversies and debates the application of any superlative generates, it inspires the same level of awe upon discovery.

I felt this sense of awe when reading E. P. Hingston’s Prefatory Note, “Artemus Ward as Lecturer,” at the beginning of Ward’s posthumous publication Artemus Ward’s Panorama (1869). You may know the name Artemus Ward as the pseudonym of Charles Farrar Browne (April 26, 1834–March 6, 1867), the printed humorist and lecturer whose career influenced that of a young Samuel Clemens when he first wrote under the name Mark Twain. Thirty years after Ward’s death, when describing the American art of telling a story, Mark Twain would commend Ward as one of the best representatives at telling it humorously:

The humorous story is told gravely; the teller does his best to conceal the fact that he even dimly suspects that there is anything funny about it…the rambling and disjointed humorous story finishes with a nub, point, snapper, or whatever you like to call it. Then the listener must be alert, for in many cases the teller will divert attention from that nub by dropping it in a carefully casual and indifferent way, with the pretence that he does not know it is a nub…Artemus Ward used that trick a good deal; then when the belated audience presently caught the joke he would look up with innocent surprise, as if wondering what they had found to laugh at.

Later Twain summarized:

To string incongruities and absurdities together in a wandering and sometimes purpose-less way, and seem innocently unaware that they are absurdities, is the basis of the American art, if my position is correct. Another feature is the slurring of the point. A third is the dropping of a studied remark apparently without knowing it, as if one were thinking aloud. The fourth and last is the pause. Artemus Ward dealt in numbers three and four a good deal. He would begin to tell with great animation something which he seemed to think was wonderful; then lose confidence, and after an apparently absent-minded pause add an incongruous remark in a soliloquizing way; and that was the remark intended to explode the mine—and it did (How to Tell a Story, 1897).

Young Mark Twain followed Ward’s professional footsteps when the Sacramento Union sent him to report on the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii) in 1866, and he returned with enough anecdotes to fill lecture halls out West.

Twain’s now famous use of language in the advertisement could be described in his own, later, language of dropping studied remarks with the printed effect of a pause by contrasting font size. Contemporary programs studying Mark Twain still rely upon advertising “The Trouble to begin at 8 o’clock”, but where would Twain be without Ward?