Introspecting with John Ashbery

Yesterday (April 20, 2016) marked the 20th anniversary of National Poetry Month. This annual event, created by The Academy of American Poets, has become the largest literary celebration in the world. Click here to discover what poetic events are happening near you.

In that spirit of celebration, today’s piece is by a most celebrated poet. John Ashbery has published more than twenty volumes of poetry and won The Pulitzer Prize, The National Book Award, a MacArthur “Genius” Grant, and just about everything else I can think of.

Ashbery approaches the blank page the way a modern artist might approach a blank canvas. The words from his broad palette are applied with a bold hand. He’s incisive about human nature, sometimes poking fun at himself in a way that shows us our own funny human frailties as well.

This meandering stream-of-consciousness piece from the sixties is one of my favorites. Enjoy!

My Philosophy of Life Just when I thought there wasn’t room enough for another thought in my head, I had this great idea-- call it a philosophy of life, if you will. Briefly, it involved living the way philosophers live, according to a set of principles. OK, but which ones? That was the hardest part, I admit, but I had a kind of dark foreknowledge of what it would be like. Everything, from eating watermelon or going to the bathroom or just standing on a subway platform, lost in thought for a few minutes, or worrying about rain forests, would be affected, or more precisely, inflected by my new attitude. I wouldn’t be preachy, or worry about children and old people, except in the general way prescribed by our clockwork universe. Instead I’d sort of let things be what they are while injecting them with the serum of the new moral climate I thought I’d stumbled into, as a stranger accidentally presses against a panel and a bookcase slides back, revealing a winding staircase with greenish light somewhere down below, and he automatically steps inside and the bookcase slides shut, as is customary on such occasions. At once a fragrance overwhelms him--not saffron, not lavender, but something in between. He thinks of cushions, like the one his uncle’s Boston bull terrier used to lie on watching him quizzically, pointed ear-tips folded over. And then the great rush is on. Not a single idea emerges from it. It’s enough to disgust you with thought. But then you remember something William James wrote in some book of his you never read--it was fine, it had the fineness, the powder of life dusted over it, by chance, of course, yet still looking for evidence of fingerprints. Someone had handled it even before he formulated it, though the thought was his and his alone. It’s fine, in summer, to visit the seashore. There are lots of little trips to be made. A grove of fledgling aspens welcomes the traveler. Nearby are the public toilets where weary pilgrims have carved their names and addresses, and perhaps messages as well, messages to the world, as they sat and thought about what they’d do after using the toilet and washing their hands at the sink, prior to stepping out into the open again. Had they been coaxed in by principles, and were their words philosophy, of however crude a sort? I confess I can move no farther along this train of thought-- something’s blocking it. Something I’m not big enough to see over. Or maybe I’m frankly scared. What was the matter with how I acted before? But maybe I can come up with a compromise--I’ll let things be what they are, sort of. In the autumn I’ll put up jellies and preserves, against the winter cold and futility, and that will be a human thing, and intelligent as well. I won’t be embarrassed by my friends’ dumb remarks, or even my own, though admittedly that’s the hardest part, as when you are in a crowded theater and something you say riles the spectator in front of you, who doesn’t even like the idea of two people near him talking together. Well he’s got to be flushed out so the hunters can have a crack at him-- this thing works both ways, you know. You can’t always be worrying about others and keeping track of yourself at the same time. That would be abusive, and about as much fun as attending the wedding of two people you don’t know. Still, there’s a lot of fun to be had in the gaps between ideas. That’s what they’re made for! Now I want you to go out there and enjoy yourself, and yes, enjoy your philosophy of life, too. They don’t come along every day. Look out! There’s a big one... -- John Ashbery

Remembering Richard Brautigan

Richard Brautigan is best known for his novella, Trout Fishing in America. I like his poems. He is said to have bridged the gap between the beatniks and the hippies.

This Saturday (January 29th) would be his 89th birthday if he were still with us. Sadly, he took his own life with a handgun in 1984. He was 49 years old.

Brautigan’s poems are terse, highly conceptual (some of his abstract metaphors border on synesthesia), and often marked by his famously quirky gallows humor.

His unconventional verses resonate with me, but not with everyone. Here are a few. Decide for yourself:

The Mortuary Bush

Mr. William Lewis is an undertaker

and he hasn’t been feeling very good

lately because not enough people are

dying.Mr. Lewis is buying a new house

and a new car and many appliances

on the installment plan and he needs

all the money he can get.Mr. Lewis has headaches and can’t

sleep at night and his wife says,

“Bill, what’s wrong?” and he says,

“Oh, nothing, honey,” but at night

he can’t sleep.He lies awake in bed and wishes

that more people would die.— Richard Brautigan

Romeo and Juliet

If you will die for me,

I will die for youand our graves will

be like two lovers washing

their clothes together

in a Laundromat.If you will bring the soap,

I will bring the bleach.— Richard Brautigan

The Donner Party

Forsaken, fucking in the cold,

eating each other, lost, runny noses,

complaining all the time like so

many people that we know.— Richard Brautigan

15 Stories in One Poem

I hate to bother you,

but I just dropped

a baby out the windowand it fell 15 stories

and splattered against

the sidewalk.May I borrow a mop?

— Richard Brautigan

A Cigarette Butt

A cigarette butt is not a pretty

thing.

It is not like the towering trees,

the green meadows, or the for-

est flowers.

It is not like a gentle fawn, a

singing bird, or a hopping

rabbit.

But these are all gone now,

And in the forest’s place is a

Blackened world of charred trees

and rotting flesh—

The remnants of another forrest

fire

A cigarette but is not a pretty

thing.— Richard Brautigan

Critical Can Opener

There is something wrong

with this poem. Can you find it?

— Richard Brautigan

15%

She tries to get things out of men

that she can’t get because she’s not

15% prettier.— Richard Brautigan

Waiting Potatoes

Potatoes await like edible shadows

under the ground. They wait in

their darkness for the light of

the soup.— Richard Brautigan

Cannibal Carpenter

He wants to build you a house

out of your own bones, but

that’s where you’re living

any way!

The next time he calls

you answer the telephone with the

sound of your grandmother being

born. It was a twenty-three-hour

labor in 1894. He hangs

up.— Richard Brautigan

San Francisco

This poem was found written on a paper bag by Richard Brautigan in a laundromat in San Francisco. The author is unknown.

By accident, you put

Your money in my

Machine (#4)

By accident, I put

My money in another

Machine (#6)

On purpose, I put

Your clothes in the

Empty machine full

Of water and no

Clothes

It was lonely.

Gertrude Stein’s Serious Play

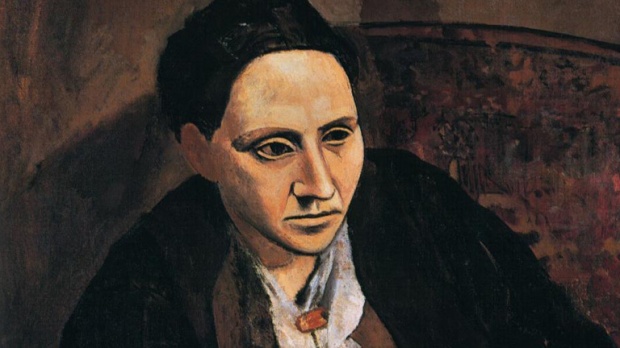

Photographs of Gertrude Stein are typically humorless.

Take this almost stern-looking image of her at work or this one with her Baltimore friends, Etta and Claribel Cone, who later visited Stein in Paris and were inspired, through her, to bring the remarkably large and impressive Cone Collection at the Baltimore Museum of Art of Cubist and Impressionist art to Baltimore.

Or this famous Picasso portrait of the author, which seems to capture the pensiveness and glumness of her era.

Even Kathy Bates’s portrayal of Stein in Woody Allen’s well-timed comedy Midnight in Paris is one of the least funny impersonations in the film.

Yet her poetry is nowhere near this sober.

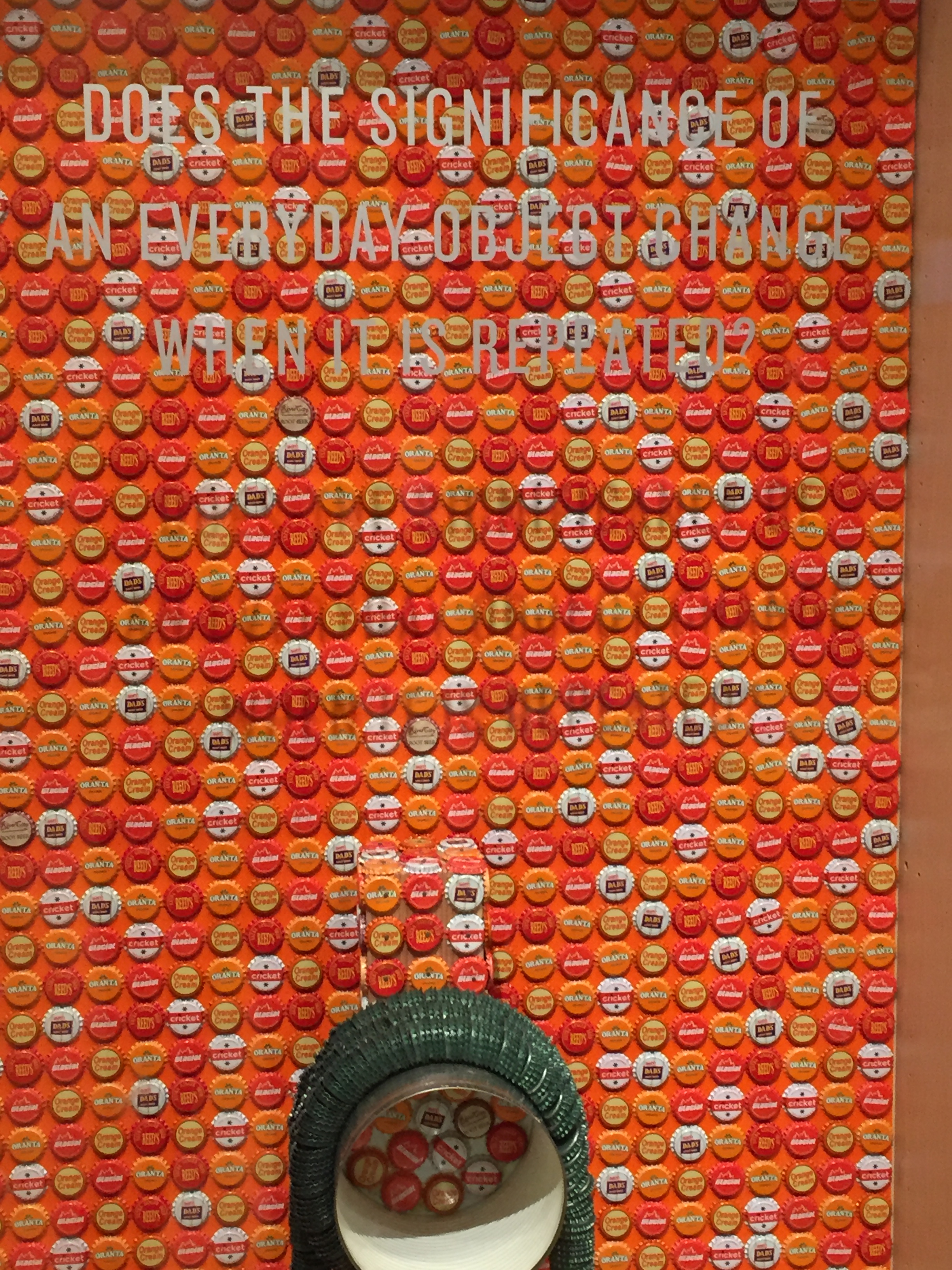

Below is a short appreciation of a few of her poems. Like conceptual art, they create meaning through grammatical disorientation, repetition, and odd angles. And like conceptual art, their strangeness can really make a reader mad unless that reader is prepared, as very few museum-goers are, to find this all amusing and then begin to dissect the puzzle.

Image from the Baltimore Museum of Art:

And as you read you may also wonder (my students often do) whether this writing is nothing more than pretentious word vomit––a clever if silly mind game––or does it contain pleasant, even human levity–even a touch of soul.

And as you read you may also wonder (my students often do) whether this writing is nothing more than pretentious word vomit––a clever if silly mind game––or does it contain pleasant, even human levity–even a touch of soul.

Does the humor, if it’s there, come from our own ability to laugh at ourselves, having discovered through her poetry that we are too precious about and at the same time not careful enough about language? Should we feel serious about overturned grammar, or should we feel playful about it, or both? Should we laugh at repetition or feel that it’s meaningful, or both?

Image from the Baltimore Museum of Art:

Nearly seventy years after her death, this kind of poetry is rich with the heaviness of her time: world wars; gender prejudice, even from those she mentored and guided; anti-semitism–even perhaps her own self-directed variety; stark inequalities between classes; and perhaps understandably bleak, bleak views of life among artists. Although her words carry this heritage and the mark of her time, she breaks open language and almost seems to free it from its literal certitudes. In this respect she is like Emily Dickinson; both were masters of language, yet in their baffling play, they almost seem to prefer giddiness and silence.

Nearly seventy years after her death, this kind of poetry is rich with the heaviness of her time: world wars; gender prejudice, even from those she mentored and guided; anti-semitism–even perhaps her own self-directed variety; stark inequalities between classes; and perhaps understandably bleak, bleak views of life among artists. Although her words carry this heritage and the mark of her time, she breaks open language and almost seems to free it from its literal certitudes. In this respect she is like Emily Dickinson; both were masters of language, yet in their baffling play, they almost seem to prefer giddiness and silence.

Image of Gertrude Stein’s deceptively dreary home while studying as a medical student in Baltimore:

Susie Asado

Gertrude Stein, “Susie Asado” from Selected Writings of Gertrude Stein. (New York: Peter Smith Publishing, 1992). Copyright © 1992 by Calman A. Levin, Executor of the Estate of Gertrude Stein. Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Gertrude Stein.

Source: The Norton Anthology of Modern and Contemporary Poetry Third Edition (W. W. Norton and Company Inc., 2003)

A Substance in a Cushion

The change of color is likely and a difference a very little difference is prepared. Sugar is not a vegetable.

Callous is something that hardening leaves behind what will be soft if there is a genuine interest in there being present as many girls as men. Does this change. It shows that dirt is clean when there is a volume.

A cushion has that cover. Supposing you do not like to change, supposing it is very clean that there is no change in appearance, supposing that there is regularity and a costume is that any the worse than an oyster and an exchange. Come to season that is there any extreme use in feather and cotton. Is there not much more joy in a table and more chairs and very likely roundness and a place to put them.

A circle of fine card board and a chance to see a tassel.

What is the use of a violent kind of delightfulness if there is no pleasure in not getting tired of it. The question does not come before there is a quotation. In any kind of place there is a top to covering and it is a pleasure at any rate there is some venturing in refusing to believe nonsense. It shows what use there is in a whole piece if one uses it and it is extreme and very likely the little things could be dearer but in any case there is a bargain and if there is the best thing to do is to take it away and wear it and then be reckless be reckless and resolved on returning gratitude.

Light blue and the same red with purple makes a change. It shows that there is no mistake. Any pink shows that and very likely it is reasonable. Very likely there should not be a finer fancy present. Some increase means a calamity and this is the best preparation for three and more being together. A little calm is so ordinary and in any case there is sweetness and some of that.

A seal and matches and a swan and ivy and a suit.

A closet, a closet does not connect under the bed. The band if it is white and black, the band has a green string. A sight a whole sight and a little groan grinding makes a trimming such a sweet singing trimming and a red thing not a round thing but a white thing, a red thing and a white thing.

The disgrace is not in carelessness nor even in sewing it comes out out of the way.

What is the sash like. The sash is not like anything mustard it is not like a same thing that has stripes, it is not even more hurt than that, it has a little top.

A Little Called Pauline

A little called anything shows shudders.

Come and say what prints all day. A whole few watermelon. There is no pope.

No cut in pennies and little dressing and choose wide soles and little spats really little spices.

A little lace makes boils. This is not true.

Gracious of gracious and a stamp a blue green white bow a blue green lean, lean on the top.

If it is absurd then it is leadish and nearly set in where there is a tight head.

A peaceful life to arise her, noon and moon and moon. A letter a cold sleeve a blanket a shaving house and nearly the best and regular window.

Nearer in fairy sea, nearer and farther, show white has lime in sight, show a stitch of ten. Count, count more so that thicker and thicker is leaning.

I hope she has her cow. Bidding a wedding, widening received treading, little leading mention nothing.

Cough out cough out in the leather and really feather it is not for.

Please could, please could, jam it not plus more sit in when.

An Afternoon with Mairéad Byrne

An Afternoon with Mairéad Byrne

Poet Mairéad Byrne came to us on a cold, windy, April Fool’s Day. Her poem “Spring” perfectly illustrated her presence on campus:

March

March

March

March

March

March

March

March

March

March

March

March

March

March

March

March

March

March

March

March

March

March

March

March

March

March

March

March

March

March

March

april

After a long winter, April and the promise of sunshine and warmth made us almost giddy as we filed into the auditorium. During her reading, students seemed a bit more . . . aware; faculty seemed a bit more . . . cheerful. We had endured 31 of the darkest days on record, and now Mairéad Byrne, our April, was reading from her collection You Have to Laugh: New + Selected Poems (2013), a compilation of witty and clever musings rife with a propensity toward sadness (“Crop”) and self-deprecation (“Things I’m Good At”; “I Went to the Doctor”). If you are new to her, Byrne is an Irish emigrant living in Providence, RI, and teaching at RISD (below: her faculty profile video).

Humor in a Sonnet’s Essence

A friend and I have been puzzling about whether sonnets are, by nature of their form and conventions, essentially funny poems. Popular views of the sonnet are that this fourteen-line poem deals with unrequited love, lovesickness, heartbreak, relationship problems, or themes of political love—none of which seem like particularly funny topics on the surface. Yet so many poets have had a good time making fun of these very tropes, creating their own sonnet parody genre in the process. But in reviewing a handful of these mocking sonnets, I wonder if they reveal opportunities for humor in the sonnet form itself and, if we go back to the original poems they mock, perhaps subtler instances of humor in those ostensibly “serious” sonnets.

The sonnet parody is very simple: it makes fun of the sonnet’s rules and themes. About ten years ago, I had a short conversation at a poetry performance with the conceptual poet Kenneth Goldsmith. When he learned that I was interested in sonnets, he took out a piece of paper and with deadpan irony wrote out the following:

8

6

“That’s my sonnet,” he said (or something like that). His “joke” is based on the mathematical conventions of the sonnet, a poem which frequently contains eight lines that build in a certain direction (the octave) followed by six lines that resolve or release that theme (the sestet). Many poets poke fun at the technical strictures of the form, which John Keats went so far as to call “chains,” yet they were chains that he, along with William Wordsworth, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and Edna Saint Vincent Millay, found paradoxically freeing.

Goldsmith’s joke was not a put-down; I got the impression that deadpan irony simply underlies his poetic philosophy. A trailblazer in the intentionally humorous, newer art of conceptual and collage poetry, Goldsmith seems to find depth in the light play—and delight in the silliness—of the poetic arts. His tone is lighthearted, though, as I recall, and even affectionate towards the silliness.

Similarly, Billy Collins’s two sonnet parodies are at the same time love songs to sonnets. His poem “Sonnet” is itself a lesson in sonnet form:

Sonnet (2002)

All we need is fourteen lines, well, thirteen now,

And after this next one just a dozen

To launch a little ship on love’s storm-tossed seas,

Then only ten more left like rows of beans.

How easily it goes unless you get Elizabethan

and insist the iambic bongos must be played

and rhymes positioned at the ends of lines,

one for every station of the cross.

But hang on here while we make the turn

into the final six where all will be resolved,

where longing and heartache will find an end,

where Laura will tell Petrarch to put down his pen,

take off those crazy medieval tights,

blow out the lights, and come at last to bed.

-Billy Collins, The Making of a Sonnet, edited by Eavan Boland and Edward Hirsch (New York: Norton Anthology, 2008), 73.

“Come at last to bed” is a deceptively simple ending for the poem, one that exposes a problem in most sonnets—as well as an opportunity for humor. The problem: a sonnet is a piece of paper, an out-of-time meditation that stands in the way of two lovers meeting. Collins suggests that the poet’s writing keeps him from real contact with the beloved. Frequently, the sonnet’s speaker writes from a place of loneliness; real connection with the beloved, either physical or emotional, depending on the poem, is somehow blocked.

About half of William Shakespeare’s 154 sonnets deal with thwarted or frustrated love, precisely because final coupling is kept in suspense in the sonnet form, or deemed impossible. Yet the tormenting experiences of heartache, however agonizing in the moment, are so hackneyed in our literature that there emerges a kind of joke in their repetition. Consider this seldom-studied sonnet by Shakespeare:

Sonnet 120

That you were once unkind befriends me now,

And for that sorrow, which I then did feel,

Needs must I under my transgression bow,

Unless my nerves were brass or hammered steel.

For if you were by my unkindness shaken,

As I by yours, you’ve passed a hell of time;

And I, a tyrant, have no leisure taken

To weigh how once I suffered in your crime.

O! That our night of woe might have remembered

My deepest sense, how hard true sorrow hits,

And soon to you, as you to me, then tendered

The humble salve, which wounded bosoms fits!

But that your trespass now becomes a fee;

Mine ransoms yours, and yours must ransom me.

Love blows are used for bartering and ransoming in this poem, and are compared to an economic exchange or a wartime practice. The poet builds the tit-for-tat banter until it falls apart in a reductio ad absurdum: if both lovers owe one another for wrong doing, shouldn’t they just throw out their accounting books and open a new leaf? The middle of the poem, around the placement of what Collins reminds us is the Italian turn, or volta, is perhaps the one genuinely tender moment in the poem: “O! That our night of woe might have remembered my deepest sense, how hard true sorrow hits.” The rest of the poem, including the mutually negating ending, is a kind of game with its own implicit sense of the ridiculous. And the blame-and-shame game reveals itself to be, within the argument of this poem, absurd.

Uncharacteristic of Shakespeare, this particular sonnet has no obvious sexual imagery. Yet, back to Collins’s last line, the word “bed,” the very last word of the Collins poem, reminds us of another world of opportunity for humor in sonnets: their frequent and often awkward use of sexual innuendo. John Updike’s conceptual sonnet parodies this truth:

Love Sonnet (1963)

In Love’s rubber armor I come to you,

b

oo

b.

c,

d

c

d:

e

f——

e

f.

g

-John Updike, The Making of a Sonnet, 328.

In his book on poetic form, Paul Fussell likens the movement from octave to sestet in the Petrarchan model to sexual arousal and release. The topic is treated with seriousness and a sense of the erotic in many examples (consider Robert Frost’s sonnet “A Silken Tent,” which can be read as a metaphor for arousal and at the same time a commentary on the pressure and release contained within sonnet form), yet this is the very trope that poets later parody. As Updike’s minimalist commentary seems to suggest, the sonnet, when stripped of its elegant imagery and rhymes (Updike retains just the rhyme coda), is no more than an adolescent reverie about sex. With its flowery language shed, a kind of funny silliness is uncovered in the sonnet form, a form which dates backs nearly a millennium. (The Tumblr site “Pop Sonnets”, which comically turns Taylor Swift, Beyoncé, and Snoop Dog songs into Shakespearean sonnets, speaks to the pop-song romance of the sonnet.)

Yet most great sonnets are about more than adolescent ideas of sex, and their humor is also at times more complex. William Carlos Williams, who resisted writing sonnets for a long time, finally came up with his own somewhat comic offering:

Nude bodies like peeled logs

sometimes give off a sweetest

odor, man and woman

under the trees in full excess

matching the cushion of

aromatic pine-drift fallen

threaded with trailing woodbine

a sonnet might be made of it

Might be made of it! odor of excess

odor of pine needles, odor of

peeled logs, odor of no odor

other than trailing woodbine that

has no odor, odor of a nude woman

sometimes, odor of a man.

Whether this is a sonnet, formally speaking, is debatable. Like Updike, Williams seems to strip the poem down to sensory and sensual details, so bare in fact that they lose their erotic context and become, just a little, funny.

But humor seems to be a key element of the tender––and ubiquitous––humiliation that underlies all love stories, happy or sad. The lover must become ridiculous and submit to a ridiculous pattern of longing, as unsexy as it is concerned with sex. Consider Gertrude Stein’s approach to the sonnet. Her “Sonnets That Please” distill the form to the essence of the lovers’ banter, and we see, as we do looking closely at all of these examples, the inherent humor in what it means to be in love—the age-old pattern of heartbreak and heart yearning to which we give ourselves, in spite of humiliation. The humanity of it, the regularity of it is as tender as it is recognizable and therefore, somehow, funny.

Sonnets That Please (1921)

How pleased are the sonnets that please.

How very pleased to please.

They please.

Another Sonnet That Pleases

Please be pleased with me.

Please be.

Please be all to me please please be.

Please be pleased with me. Please please me. Please please please with me please please be.

-Gertrude Stein, Bee Time Vine (Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1953 and 1969), 220.

Poetry Corner: James Tate

Tracy Wuster

As a poor-quality young poet, my verses were overwrought, melodramatic, and a bit odd. Then I discovered James Tate, and I decided that if I was to be a poet, then an odd humor would be my game. Years of teenaged notebooks were filled with poems cribbed from Tate–aping his tone, style, and playful surrealism. Then I discovered that I didn’t want to be a poet. I’d leave that to my older brother.

After a few short films that might have been influenced by Tate, I ended up in grad school studying humor. No poetry, per se, in my research, but I like to go back to Tate once in awhile to rediscover some of that absurd magic that shaped–and might continue to shape–my experience of language.

With our poetry editor away for a few months, I decided to step in with a couple of my favorite poems by Tate. I also found this article–James Tate: “The Cowboy” How to be funny and sad. BY STUART KRIMKO–which discusses one of Tate’s poems in terms of humor. Here is Tate reading some of his poems, with a biography. And two of Tate’s poems.

Teaching the Ape to Write Poems

They didn’t have much trouble

teaching the ape to write poems:

first they strapped him into the chair,

then tied the pencil around his hand

(the paper had already been nailed down).

Then Dr. Bluespire leaned over his shoulder

and whispered into his ear:

“You look like a god sitting there.

Why don’t you try writing something?”

James Tate, 1943

from Absences. Copyright © 1970 by James Tate.

The List of Famous Hats

Napoleon’s hat is an obvious choice I guess to list as a famous hat, but that’s not the hat I have in mind. That was his hat for show. I am thinking of his private bathing cap, which in all honesty wasn’t much different than the one any jerk might buy at a corner drugstore now, except for two minor eccentricities. The first one isn’t even funny: Simply it was a white rubber bathing cap, but too small. Napoleon led such a hectic life ever since his childhood, even farther back than that, that he never had a chance to buy a new bathing cap and still as a grown-up–well, he didn’t really grow that much, but his head did: He was a pinhead at birth, and he used, until his death really, the same little tiny bathing cap that he was born in, and this meant that later it was very painful to him and gave him many headaches, as if he needed more. So, he had to vaseline his skull like crazy to even get the thing on. The second eccentricity was that it was a tricorn bathing cap. Scholars like to make a lot out of this, and it would be easy to do. My theory is simple-minded to be sure: that beneath his public head there was another head and it was a pyramid or something.

From Reckoner, published by Wesleyan University Press, 1986. Copyright © 1986 by James Tate

Langston Hughes on Hard Laughter

Langston Hughes’s roughest book of poetry is also an homage to laughter.

In 1925 Langston Hughes lived with his mother on the north side of S Street, a few short blocks from Dupont Circle in Washington, D.C. The tiny two-story square row home, painted in deep brown trim today, is set back from the sidewalk. A meandering path leading up to the house meets, at the sidewalk’s edge, the meandering path of the house next door; they bend together in the rough shape of a heart. The first story of the home has a large single window, broad and revealing like a storefront display. The second and top story, where Hughes most likely lived and wrote, seems squat, pared down, resting atop the broad window. The house itself is inconspicuous, quiet, and low––slyly hidden by the grander-seeming homes surrounding it.

Langston Hughes lived in many places during his pivotal year in Washington, but, walking by this house one day recently, I found myself wondering if it was here that the seeds were planted for his 1927 book of poems, Fine Clothes to the Jew, a book famous among a small group of scholars for its controversial release but that remains unknown to many.

Langston Hughes lived in many places during his pivotal year in Washington, but, walking by this house one day recently, I found myself wondering if it was here that the seeds were planted for his 1927 book of poems, Fine Clothes to the Jew, a book famous among a small group of scholars for its controversial release but that remains unknown to many.

Today the book is out of print. Google Books does not “preview” it, most libraries do not carry it, and even The Library of Congress cannot locate their lone copy. A small number of first editions are available on-line for upwards of a thousand dollars. The book is worth far more. (Two Collected Works of Langston Hughes editions, Arnold Rampersad’s and Dolan Hubbard’s, contain the poems from Fine Clothes to the Jew.) The book received scathing reviews when first released, mostly from Hughes’s fellow literati in Harlem, for its seemingly unabashed and degrading depictions of African Americans.

In situation and appearance, Langston Hughes’s mother’s home resembles the paradox in the reception history of Fine Clothes to the Jew. The house is removed, easy to miss, simple, and confined in the heart of a bustling city. Yet the house is also solid and stern, its gazing window luminous. Likewise the poems in this book are hard, describing people who live hard lives in the brusque city or lonely, rural south. Actually, written in six parts alternating between the city and the country, Fine Clothes doesn’t describe these people; rather, each poem is spoken in the voice of a different, struggling soul—the prostitute, the pimp, the abusive husband, the abused wife, the player, the played, the child, the worried parent, the broken-hearted, and the philanderer—to name just a few of the characters. A burdened consciousness of race and ethnicity is made overt notably in the book’s title, which pairs beauty or opulence (fine clothing) with the ugliness of bigoted social perceptions.

Joker Poe, Part 2: The Poet as Prankster

In my last post, I suggested that Edgar Allan Poe was essentially a practical joker. That is, although he remains best known today for tales of terror and mystery, of the Grotesque and Arabesque, Poe in his own time was very much a satirist or humorist. Not infrequently, the joke is on us, the readers, who are duped into believing the most incredible things, as becomes embarrassingly clear in “The Balloon-Hoax” or “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar,” for example. After all, Poe was the philosopher who was able to explicate “diddling” – that is, tricking or swindling – as “one of the exact sciences.” In his various hoaxes, satires, and “diddles,” Poe proved himself to be an accomplished prankster, which unsurprisingly stood him in good stead in the bumptious literary marketplace of his era.

Less obvious, perhaps, is the way that Poe the Poet might also be considered a practical joker. Poe’s poetry, unlike his more well-known prose tales, is generally thought to represent the Romantic ideals of supernal beauty. In the best poems, Poe’s mastery of sound and sense helps to produce poems of haunting loveliness, as in “The Raven” or “Annabel Lee.” But, then, it should also be observed that many of his poems appear to be crudely imitative; Poe concedes that his earlier poems were essentially attempts to reproduce Byron, for instance. Some might be labeled failed experiments, while others appear to be downright awful. Who can listen to “The Bells” more than once without going mad? The pealing repetitions are so intensely jangling to the nerves that one can only conclude that such was the poet’s intention. The point of the poem is to drive us crazy! But even in Poe’s most successful poems, there is a lurking sense that Poe is putting one over on us. The reader of Poe’s poems must always be on guard, as one cannot shake the vague suspicion that the poetry may be an ornate armature upon which to hang a joke in poor taste. However, we can identify at least one poem in Poe’s corpus that is unquestionably also a practical joke: “O Tempora! O Mores!”

“O Tempora! O Mores!” is one of Poe’s earliest poems, although it was not published until years after his death. Its title, deriving from Cicero’s famous lament and translated “Oh, the times, Oh, the manners [or customs]!,” is already suggestive of humor in a modern context. The phrase is generally reserved for those satirizing the jeremiads of the era. Studying the poem more closely, we see that the jaunty doggerel appears to lampoon a single character, a handsome salesman or clerk who has charmed his lady customers, but who the poet recognizes as an unintelligent and unworthy “ass.” The poem was written sometime in 1826, when Poe was only 17 years old, and in my own reading I had taken it to be a satirical critique of the crass, commercial culture of the United States in the nineteenth-century. That is, like the biographer Kenneth Silverman, who noted the poem’s “scorn toward the clerk as a plebian vulgarian, and its contempt for the world of merchandising,” I saw the young poet in “O Tempora! O Mores!” as a Romantic bemoaning the unrefined, boorish, middle-class values of the day. Like nearly everyone else, I was perplexed about the final word of the poem, in which the speaker names his object of ridicule, “Pitts.” But, in the end, I was able to file this away as mildly interesting juvenilia.

However, I heard a fascinating talk by renowned scholar Richard Kopley at the 2014 MLA convention, which shed light on the backstory of the poem. (An abstract of the talk appears in The Edgar Allan Poe Review 14.2 [Autumn 2013]: 250–251.) Alas, I can offer only a teaser here based on my faulty memory of the presentation, but Professor Kopley is currently working on a scholarly biography of Poe, which I have no doubt will be well worth the wait. For now, let me just say that the poem “O Tempora! O Mores!” was the acid coup de grâce of an elaborate practical joke.

In the Archives: Mark Twain’s Infectious Jingle– “A Literary Nightmare” (1876)

Tracy Wuster

Mark Twain’s “Literary Nightmare” (1876), published in the Atlantic Monthly, represents an early example of a “viral” piece of popular culture. The “Viral Text” project at Northeastern University is tracing 19th-century newspaper stories as they circulated, and “A Literary Nightmare” might be a unique example–being a story about a viral text–in this case, a poem–and its infectious effects, which in turn helped spread the original poem, Mark Twain’s story about it, and the very genre of poetry across the nation and, possibly, around the world. The story even inspired a song. And was being discussed as late as 1915.

The poem presented the key example of “horse-car poetry” that enjoyed a brief vogue as popular doggerel. A discussion of the phenomenon of “horse-car poetry” was printed in Record of the Year, A Reference Scrap Book: Being the Monthly Record of Important Events Worth Preserving, published by G. W. Carleton and Company in 1876. The story, beginning on page 324, details how a New York rail line posted a placard on fares that became a poetic sensation, leading to Mark Twain’s use of the lines in his story. The phenomenon of “horse-car poetry” then, according to the Record of the Year, spread to other cities and countries, causing an “epidemic” that aroused passions and even violence. The Record of the Year contains one story of a woman literally possessed by the sketch, reading in part:

The entire scene is worth reading at the link above.

Mark Twain’s extended comic sketch details the hypnotic, yet meaningless, power of humorous writing to infect one’s mind like a virus. Entitled “A Literary Nightmare” (February 1876), Twain’s piece starts with a verse of poetry:

“Conductor, when you receive a fare,

Punch in the presence of the passenjare!

A blue trip slip for an eight-cent fare,

A buff trip slip for a six-cent fare,

A pink trip slip for a three-cent fare,

Punch in the presence of the passenjare

CHORUS

Punch, brothers punch with care!

Punch in the presence of the passenjare!”

These lines, the narrator “Mark” writes, “took instant and entire possession of me.” For days, the only thing in his mind are the lines of verse—they keep him from his work, wreck his sleep, and turn him into a raving lunatic singing “punch brothers punch…” After several days of torture, he sets out on a walk with his friend, a Rev. Mr. ——- (presumably his good friend Rev. Joe Twichell). After hours of silence, the Reverend asks the narrator what the trouble is, and Mark tells him the story, teaching him the lines of the jingle. Instantly, the narrator puts the verse out of his mind. The Reverend, on the other hand, has “got it” now.

You can read the sketch in its entirety below.