Comedy, Tragedy and the Rise of Trump

Since Donald Trump became the presumptive nominee of the Republican Party for President of the United States in early May , pundits and commentators have attempted to understand how this once unthinkable scenario came about. In fact, since his strong showing in the Iowa caucus this winter, people have tried finding the culprit for the rise of the reality television personality.

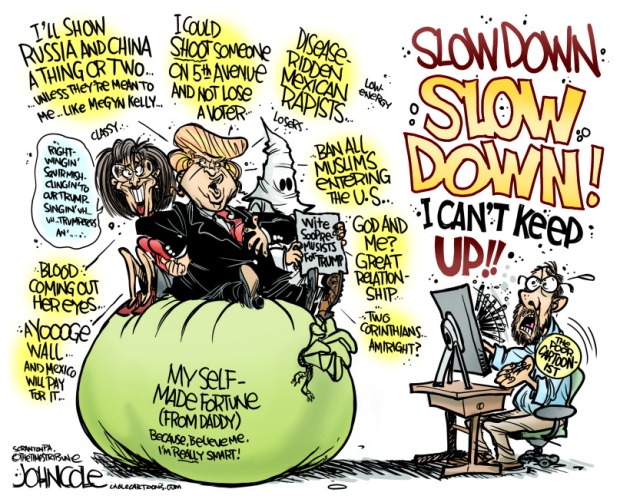

The old saying claims success has many fathers while failure is an orphan. In the case of Trump, however, it seems the failure of the political system has many fathers. During the past months President Obama has been blamed for the rise of Trump, so has the Republican Party, so has income inequality, and racism, and political science. The most usual suspect, however, remains the media. The case has been made that the media, and television especially, gave Trump unlimited airtime to peddle his particular brand of racism, xenophobia, nationalism, and conservatism. Leslie Moonves, executive chairman of CBS, articulated the relationship between media and Trump when he admitted that “it may not be good for America, but it’s damn good for CBS”.

The lavish media attention given Trump includes late-night comedy, the former Apprentice host has appeared on all three network’s late-night shows, and even hosted an episode of Saturday Night Live on NBC. Showbiz politics is nothing new in American politics; celebrity has been a part of presidential elections for decades as historian Kathryn Cramer Brownell has shown. I have previously written on this blog about late-night campaigning and how integral comedy has become to presidential communication. What makes the appearance of Donald Trump on Saturday Night Live for example so controversial, however, is that his statements are far outside the political mainstream. Balancing the quest for ratings with the risk of normalizing the rhetoric of Trump, while keeping the comedic integrity, has made for very different late-night appearances.

Donald Trump on the Late Show with Stephen Colbert in September 2015.

Happy Birthday, Samuel Langhorne Clemens. Not you, Mark Twain.

Tracy Wuster

November 30, 2015 will be celebrated as the 180th birthday of one Mark Twain—novelist, humorist, and all around American celebrity. I, for one, will not be celebrating.

You see, I recently finished up a book about Mark Twain, and I know, for a

fact, that Mark Twain was born on February 3,  1863. Or thereabouts. No one knows for certain, but that is as certain as we can be, so that is enough. And not so much born, but created, or launched…inaugurated…catapulted…

1863. Or thereabouts. No one knows for certain, but that is as certain as we can be, so that is enough. And not so much born, but created, or launched…inaugurated…catapulted…

That means that this February 3, 1863 will be Mark Twain’s 153rd birthday, which is not that fancy of a number, but it is getting up there for someone still so famous as to have people writing books about him—and more importantly, people reading books by him.

Sure, everyone knows that “Mark Twain” was really the pseudonym of Samuel Langhorne Clemens. Even early in his career, almost everyone knew that, often using the names interchangeably, as most Americans still do. Not as many people know the names Samuel Clemens used an abandoned before creating Mark Twain: “Grumbler,” “Rambler,” “Saverton,” “W. Epaminondas Adrastus Blab,” “Sergeant Fathom,” “Quintus Curtis Snodgrass,” “Thomas Jefferson Snodgrass,” and “Josh.” Selecting “Mark Twain” was clearly a wise choice, although the name would have had a second, nautical meaning for many nineteenth century folk.

Samuel Clemens mixed up the use of his given name and his chosen name—making the whole distinction a mush of confusion that is either a bonanza of psychological material or, alternately, meaningless. For most people, I would guess the distinction is meaningless trivia, which is fine. I’m just happy people still know and read books by Mark Twain. But, I for one, will still grumble when people wish Mark Twain a “Happy Birthday” each November 30th, and I will still try to correct them by pointing out that the “Mark Twain” they refer to really was born—or created—on February 3rd, 1863.

But what does it matter?

The John Oliver Effect, Humor, and Thesis Statements

I wish I had coined the phrase: “The John Oliver Effect.” I wish I had jumped onto the John Oliver bandwagon before this past June when I first wrote about it for Humor in America. I wish more people had read my post in June. Here is the link to it for those who want a second chance: John Oliver, FIFA, American Humor, and Topic Sentences. The title is a bit long. I see that now. This follow-up post is better since is shamelessly rides the crest of the “John Oliver Effect” wave. About 60 words into the post, and I have used it three times, including the title. I am seeking traction. John Oliver Effect.

The phrase was coined by Victor Luckerson for Time online (20 January 2015): How the ‘John Oliver Effect’ is Having a Real-Life Impact. At least I think he coined it. In any case, although he introduces it as “so-called John Oliver Effect,” implying that someone had already “called” it, the internet has decided that he coined it based on the multitude of sources that use it and cite him as the originator. I’m in, too.

In a compelling article, Luckerson examines how reactions to particular sketches on Last Week Tonight have encouraged specific responses in the public square. In an especially useful post following the same idea, Sara Boboltz, for the Huffington Post (HuffPost Comedy) discusses ten specific segments from the show: 10 Real-Life Wins for John Oliver. Although I certainly quibble with the tendency in both pieces to use the term “real-life,” I will avoid a tedious existential argument here and simply say that both writers successfully capture a crucial transition in television comedy history. The list of segments from Last Week Tonight with John Oliver that deserve substantive attention in the pubic sphere is growing. The show, in no uncertain terms, encourages and even demands responses from politicians, policy-makers, public figures, and, well, from all of us.

This follow-up post on the show reiterates my belief that the most important characteristic of Last Week Tonight with John Oliver is the essential quality of the writing. In particular, the thesis-driven approach to satirical humor that the show promotes is deepening the dialogue on any of a number of issues, and it does so with great skill and, so far, substantive success. It is television comedy in long-form, expository writing. What Last Week Tonight is proving that American audiences, indeed, can have an attention span greater than amphibians, current polling on the presidential race notwithstanding. Moreover, humor is effective in proving points. Who knew?

Comedian John Oliver poses for photographers backstage during the 41st International Emmy Awards in New York, November 25, 2013. REUTERS/Carlo Allegri (UNITED STATES – Tags: ENTERTAINMENT) – RTX15T8O

More and more viewers and critics are noticing. The show has earned four Emmy nominations for 2015: for “Outstanding Variety Talk Show Series”; “Outstanding Picture Editing for a Variety Series”; “Outstanding Interactive Program”; and “Outstanding Writing for a Variety Series.” It is the last one that has the most implications for the quality of the show and its long-term impact on American humor and satire. We will find out the results on the Emmys to air on Sep. 20th. Although the competition is formidable, the conclusion should be clear. Long form writing deserves its due.

In the much heralded–and very funny–Daily Show with Jon Stewart farewell episode, the brief banter between Stewart and Oliver was both funny and telling. The core joke, quite simply, was built around the definitive difference between the two shows and their approaches to humor and culture. Here is a link to the segment, wherein Oliver’s part starts five minutes into the seven-minute clip: John Oliver on Jon Stewart’s final Daily Show. The bit begins as Oliver goes on and on about his first day on set. Stewart tries to get Oliver to be more brief in his narrative, saying, “We’re gonna have to pick up the pace, just a smidgen.” To that Oliver responds, “No, no, no, no…we can’t. When something’s important, it’s worth taking the time to discuss it in depth. I’m talking fifteen, eighteen, even twenty minutes, if necessary. Otherwise, what are you really doing?”

This is a direct reference to the writing style of Last Week Tonight with John Oliver, wherein the thesis-driven segments run, generally, 15-20 minutes. The comic but pointed rhetorical question is a good one for any politically conscious humor: “What are you really doing?”

Clearly, Last Week Tonight is accomplishing something substantive. Allie VanNest in Parse.ly (8 Sep 2015, Measuring the Impact of ‘The John Oliver Effect’) demonstrates a clear impact of Oliver’s segment examining chicken farming. Here is a link to the segment on YouTube: .

VanNest includes a graph revealing the impact this particular segment had on public awareness. The data is not ambiguous here. VanNest acknowledges that the more seemingly obscure the subject is, the more easily the John Oliver Effect can be measured. Still, the graph below nonetheless offers a formidable indication of the potential of the approach that Last Week Tonight is taking.

I argued in the earlier piece that Last Week Tonight with John Oliver, though equally funny to any late-night peers, aspires to alter public debate in a much more clearly articulated manner than any of its predecessors. It is all in the thesis and the sustained argument, all supported by carefully considered evidence, all made palatable with humor. Here is my advice to writing teachers: use John Oliver to teach argumentative writing. Everyone will win with this approach. Call it the John Oliver Effect. It may actually change things.