Mark Twain caused all kinds of trouble. In fact, he reveled in it.

He famously advertised his lectures with the tag line, “The Trouble Begins at 8,” and was apparently delighted to share that line with his favorite blackface minstrel troupe, the San Francisco Minstrels. Both Twain and the minstrel troupe played around with variations—”The Insurrection Begins . . . ,” “The Orgies Commence . . .,” “The Inspiration will begin to gush . . . ,” “The Trouble Commences . . .”—but both used the more famous version for years without interruption. One thing is sure. The phrase was indelibly associated with both: “trouble” was their trademark.

The San Francisco Minstrels were not what we expect when we think of blackface performance—at least, they weren’t what I expected when I first began researching them—for their popularity was based in part on their political satire. They were satirists who believed that the only possible fodder for a sacred cow was a stick of dynamite, and while they did indeed parody black people, they parodied everyone; they were what John Strasbaugh calls “poly-ethnic offenders” or what Chris Rock terms “equal-opportunity offenders.” And while some of their routines are ugly with racist underpinnings, other routines question these stereotypes as essential categories, challenging ridiculousness, corruption, and pretension wherever they see it. A surprising amount of their material has little direct connection to race at all. Known for end-men Charley Backus’s and Billy Birch’s free-wheeling improvisation on current events, the San Francisco Minstrels attracted nineteenth-century audiences in much the same way that Jon Stewart or Stephen Colbert do today: their satiric spin on current events, politics, and entertainment.

M. D. Landon once quipped that Charley Backus had been “censured by the Speaker of the California Legislature for making fun of his brother members. This broke poor Charley’s heart and he joined a minstrel company so’s to be where no one would grumble when he indulged in a little pleasantry”[1] Emma Benedict Shephard remembers that they “always managed to hit the public men or local politics in their questions and answers”[2] and Francis Smith, that “the San Francisco Minstrels [Hall was] packed on Saturday afternoons with Wall Street brokers, roaring over the personal jokes, those never-to-be-forgotten end-men, Billy Birch and Charley Backus, had prepared for them overnight.”[3]

Twain famously wrote in Pudd’nhead Wilson’s calendar that “It could probably be shown by facts and figures that there is no distinctly native American criminal class except Congress.” Charley Backus held a similar view. When asked if he would like to run for Congress, the blackface actor quipped, “No, indeed . . . I only have to play the fool a few hours on the stage, at night; but in Congress, I’d have to play that rôle all the time.”[4] It’s pretty easy to see why Twain enjoyed their performance style.

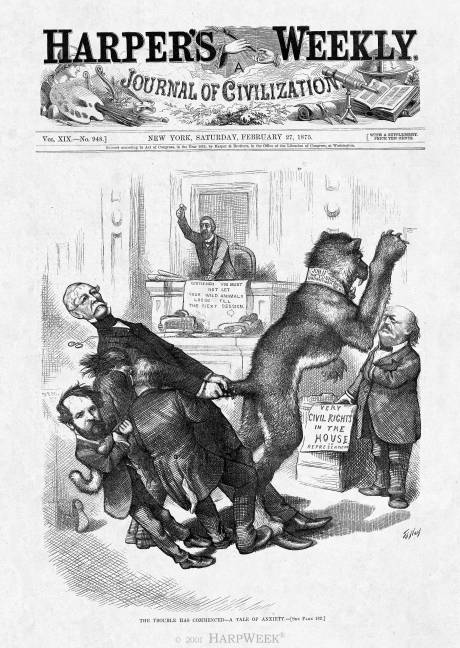

So when in 1875, Thomas Nast published a political cartoon in Harper’s Weekly that bears the caption, “The Trouble Has Commenced – A Tale of Anxiety,” there is little doubt that his audiences would have gotten the reference. The cartoon offers a caricature of Congressional debates over proposed Civil Rights legislation. Congressman John Young Brown of Kentucky was vigorously attacking the Republican efforts to pass the bill during a lame-duck session. Brown’s remarks got personal, and when Speaker of the House Blaine questioned his intent, Brown replied, “If I was to desire to express all that was pusillanimous in war, inhuman in peace, forbidding in morals, and infamous in politics, I should call it ‘Butlerizing.'”[5]

His insult was directed at Benjamin Butler, Congressman from Massachusetts and a former Union general notorious for his harsh occupation of New Orleans and his use of international law to argue that escaped slaves were “contraband” of war that he was not obliged to return to their owners, earning him the title of “Beast Butler.” When censured by Speaker Blaine, Brown apologized, saying that he intended “no disrespect,” and with comic timing born of the political theatre, he added “. . . to the House.”

Nast’s cartoon presents Butler as standing calmly under the threat of Brown’s beast, head thrown back, eyes on the attacker towering above him, reaching with his left hand into his right inner suit coat pocket, like a left-handed Napoleon or as though he’s reaching for a concealed weapon. The penchant for insult and witty repartee, the association with the Civil Rights act, Butler’s reputation as a general and a legislator, and the underlying threat of violence all make the cartoonist’s reference to Mark Twain’s and the San Francisco Minstrels’ “trouble” an obvious choice: here, in the halls of Congress and in the US at large, “The Trouble has Commenced.”

Butler’s association with the minstrel stage was established before this. About six years before, in December 1869, he’d had an infamous exchange with one of the other figures in this cartoon, Samuel S. “Sunset” Cox, pictured here as holding Brown’s tail in the lower left front corner. Cox, at that time fairly recently elected to Congress from New York, shocked members of the House with a “vigorous denunciation of Butler, whom he characterized as being better suited for an end man in a burlesque show than a seat in Congress.”[6] Butler, completely unruffled by Cox’s attack, caused a furor in the House and around the country by waving his hand casually and quipping dismissively, “Shoo Fly, Don’t Bodder Me!”

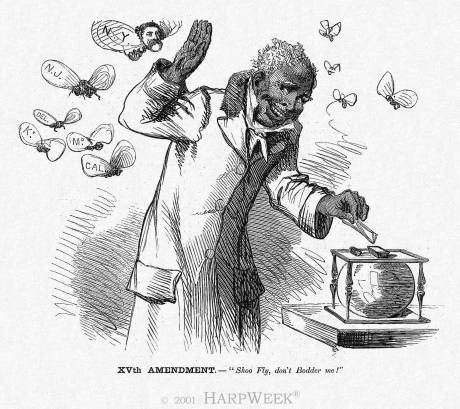

Shoo Fly was, of course, one of the nineteenth century’s most famous blackface minstrel tunes,[7] and its dismissive insouciance was taken up in a number of causes and contexts — as this cartoon from Harper’s on March 12, 1870 shows: XVth Amendment. This unsigned cartoon shows an African Amerian man casting his vote while shooing away merely mildly irritating flies—the states that voted impotently against ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment. Congressman Butler waved away the vituperative invective of his Democratic colleague in the same vein.

While it is not yet clear whether Butler’s “performance” of Shoo Fly pre-dates or makes use of the San Francisco Minstrels’ performance of it, as the exact dates are difficult to pin down, both occurred in December of 1869. Ever with their finger on the pulse of current events, the San Francisco Minstrels showcased the song (December 1869); Johnny Queen and Billy West of the San Francisco Minstrels performed Shoo Fly week after week to high acclaim, and by December 27, Birch and Backus redoubled the onslaught in clear response to the Butler-Cox incident, with a parody skit called “The Fat Men’s Ball — Shoo Fly–Weight don’t bodder me.”

That blackface minstrel images could be used in support of such causes may seem surprising to us, but blackface embraced ambiguity, contradiction, and pusillaninimity. While it certainly contained some of the worst racial derogation our country has seen, it also left room for contradictory and often subversive voices.

Blackface performance danced defiance like few other American cultural practices, insisting that race, social class, and social inequities all remain on the table simultaneously. Though this often meant that horrific racial caricatures were used as scapegoats for the elevation of white lower classes, it also meant that those caricatures are complicated by the appearance of their opposites on the same stage, by surprising moments of solidarity, when dancing defiance of unreasonable, corrupt power or condescending attack meant more than other differences. “Trouble” came in all guises: Twain, Nast, the San Francisco Minstrels, and others gleefully embraced it.

And their critique often seems surprisingly modern, surprisingly related to our own time: “Mr. Addison Ryman in the good old days of the San Francisco Minstrels used to give advice to young men on the threshold of life. ‘What does Mr. Samuel J. Tilden say? Make your money honestly, young man; and if you can’t make it honestly—go into railroads.’”[8]

Or sub-prime mortgages.

[1] Landon, Melvin D. [“Eli Perkins”]. “Scaring a Connecticut Farmer.” The Library of Wit and Humor, Prose and Poetry: Selected from the Literature of all Times and Nations, Volume 3 (1884). A[insworth] R[and] Spofford and Rufus E[dmonds] Shapley, eds. Philadelphia: Gebbie & Co., 1892, p. 191.

[2] Knapp, Mrs. Shepherd (Emma Benedict). Hic habitat felicitas : a volume of recollections and letters. . Boston : W. B. Clarke co., 1910.

[3] Smith, Francis Hopkinson, with Frank Berkeley Smith. Enoch Crane. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1916.

[4] Lowe, Paul E[milius], ed. After-Dinner Stories. Philadelphia: David McKay, 1916.

[5] “Beast Butler” reprinted from the Courier, in United States. Congress. House Select Committee on the Condition of the South. [Report of the Select Committee on that portion of the President’s message relating to the condition of the South]. Washington: Govt. Printing Office, 1875. p. 188.

[6] Trissal, Francis Marion. Public Men of Indiana: A Political History from 1860 to 1890. Volume 1. Hammond, Indiana: W. B. Conkey Co., 1922. p. 215.

[7] Though Shoo Fly has been mistakenly associated with Billy Birch of the San Francisco Minstrels, it was not. Attributed first to Helon Johnson, an African American blackface performer with Charles Hicks’s Booker and Clayton’s Georgia Minstrels, who allegedly taught the song to Birch in 1854 or 1865, the song was published and widely sung on the blackface stage by 1869. As is usual with the minstrel stage, it was “claimed” by many, and its composition has been variously attributed to Rollin Howard, Frank Campbell, T. Brigham Bishop, and Billy Reeves, but it seems have sprung from Afro-Panamanian or African American folk roots, and carried to America by Helon Johnson.

[8] The New Music Review and Church Music Review 7.74 (January 1908): 71.

©Sharon McCoy 24 October 2011

This blog is adapted from a section of the book manuscript I’m finishing, “Nothing but Trouble: Blackface in Mark Twain’s America.”

Check out Harper’s wonderful collection of online political cartoons from the nineteenth century at this link: Harper’s.

Editor’s Note: I have added the cartoons mentioned from HarpWeek. All copyright is maintained by that site. Images are used under fair use provisions. (TW)

[…] Mark Twain and Black Face […]

I came across your post when looking for information on Add Ryman. Copies of his work appear to be scarce. You might want to know that I am about to add his ADD RYMAN’S STUMP SPEECHES (New York Popular Pub., c1882 Dick & Stecher) to the Tarver Elocution Collection at Ohio State. No other copy is listed in WorldCat. Currently I am trying to find out if Ryman’s SPEECHES has the same text as Hughey Dougherty’s STUMP SPEAKER (one copy known). I suppose many of the bits in Ryman’s book were delivered in blackface, but I find support in their content for your point that humor of this sort by no means rested entirely on racism.

Best,

Jerry Tarver

Jerry,

I am not only appreciative, I am delighted.

The collection sounds wonderful–and you are right about my particular interest in this book. I have been looking for it for a long time, having seen references to it. Ryman fascinates me. I am writing a book on the San Francisco Minstrels and Mark Twain, and what I have been able to find of his contributions to their stage are intriguing to say the least.

Is there any chance that any of the Tarver Collection will be digitized? I will certainly want to come to the library and see the collection in person, but it would help enormously if I could see a copy of it sooner. I would, of course, fully cite the collection and the library.

I have not seen Dougherty’s book, but from what I remember of the songs by him that I have seen, I would guess that the two are materially different.

If you see this response, I would love to correspond with you in more depth. My email address is sdmccoy@uga.edu.

Warm regards,

Sharon

Jerry, I came across a toy made around 1880, and it has Gov. Add Ryman on the front and also on another part it says ” School Question San Francisco Minstrel. Did you ever come across any information about this toy which is made by Ives corp. in Conn.

Thanks John Evans

Hi, John,

You’d probably need to get in touch with Jerry directly, but I’d love to talk with you about the toy. I don’t have information about this toy, specifically, but one of my areas of research is the San Francisco Minstrels, along with other troupes in the post-bellum era and their ephemera; “The School Question” was one of Add. Ryman’s routines. You may reach me at sdmccoy@bellsouth.net. I’d enjoy talking with you.

Warm regards,

Sharon McCoy

John,

A fascinating find, but I’m sorry I can’t shed any light on it other than to say it’s certainly rare and well worth preserving to show how word got around before social media. In my area of interest, the elocutionists of nineteenth century America naturally relied primarily on paper items (cards, broadsides, photographs) for advertising. While one might think that metal or wooden objects would survive the elements more easily than paper, you have to remember the human tendency to break and discard. I hope you keep digging and let us know what you find. By the way, it’s great to see this thread alive again (Hi, Sharon).

Best,

Jerry

Reblogged this on Humor in America and commented:

Today, we are reposting Sharon McCoy’s piece from several years ago on Mark Twain and blackface minstrelsy. Enjoy.