Furries: A Convenient Comedic Fiction

My bar trivia team changes its name with each new tournament. Every few months, this becomes a ritual where I pitch a series of disgusting and/or esoteric names like Bridget Jones’s Diarrhea or Rod Torfulson’s Armada Featuring Herman Menderchuk and the group rolls their eyes as they reject my ideas. In the last go-around, I became insistent that we name ourselves after one of the gangs from the 1979 cult film The Warriors. For no particular reason, I especially wanted to be called The Baseball Furies. In a flash of brilliance and to my surprise, a teammate suggested that we be called The Baseball Furries – combining the fictional gang with the name for people whose sexual fetish is to dress up like a Care Bear.1

This was a good name for a trivia team, but considering their usual aversion to jokes that might offend, I was surprised that the team was amenable to this name. It was difficult for me to imagine naming our team after any minority group – sexual or otherwise. I had to conclude that everyone pretty much assumed there to be no furries in the bar, nor would there be any in our social groups that could possibly take offense.

Furries might exist somewhere, but nowhere, we assume, near us. It makes them a convenient reference for a laugh about other people’s perversion. And yet, our assumption that it is a minority group so small as to be nonexistent belies our and everyone else’s assumed familiarity with the practice. For a group that barely exists, there sure are a lot of people talking about furries. This is why the group is “fictional” – the amount of discourse that surrounds furry-ism immeasurably outweighs the reality of its practice. That it is other people’s perversion is key. Furry fetishism is so far off the radar of seemingly possible sexuality that it has come to stand in as a marker for sexual deviance in comedy. It is a common target for television comedies like The Drew Carey Show, Entourage, and Check It Out with Dr. Steve Brule. And in a comic twist on “rule 34,” furry culture is the topic of a lot of internet mockery.2

In an episode of 30 Rock, unlucky-in-love Liz Lemon finds a seemingly great guy who is single. Too good to be true? Yes – he’s a furry. This is reminiscent of the “all the good men are gay” sitcom trope where a woman falls for a gay man. One variation of this trope, which became the basis for Will and Grace, has a female character only realize at a humiliatingly late moment that her crush is gay. The key difference between Grace and Liz, however, is that while Will’s sexuality allowed the pair to easily reformulate their relationship as friends, Liz was so horrified at the prospect of furry-ism that it was borderline unimaginable for her to spend any more time with this man. And as the primary surrogate for the audience, it was implied that the we too should be comically horrified by the prospect of explorations in furry sexuality. That kind of experimentation was Jenna’s domain.

It is difficult to imagine, in the current media environment, having a character like Liz Lemon be horrified by a homosexual. Homer Simpson could get away with homophobia in 1997, as long as he learned tolerance by the end of the program. Although homophobia still exists in American comedy, the kind that would blatantly encourage a kind of abject dread is not terribly common in contemporary mass media. This is due to a host of factors, notably general changing social mores as well as more pointed calls for responsible representation by gay rights groups. Jokes constantly change their particulars while maintaining a common structure. That some gay jokes have shifted their target to furries is thus less notable than the fact that jokes have shifted from an identifiable group to a practically unidentifiable one.

And this is neither only nor simply an issue of redirected homophobia. Jeffrey Sconce provocatively suggests that “the unconscious is slowly dying out” in part because of, “the Internet’s ability to actualize any and all erotic scenarios in seconds.” From a Freudian standpoint, the lack of an unconscious would obviate the need for humor or sexual shame, so why do we seem stubbornly stuck with jokes at the expense of furries? Furry jokes demonstrate at least some aspect of the unconscious is alive and that it is desperately trying to Other furries in an attempt to normalize the things of which we are all silently ashamed. We need furries because they make your internet browser history seem less embarrassing. But beware. Once that stuff becomes normalized, there will be few places left to go for the thrill of perversion. Someday, we will all become furries.

1I am aware that sex is supposedly only a part of this subculture, but let’s be honest – that’s how everyone thinks about this group. Read on in any case, because this relates to my point.

2Rule 34 states that on the internet, if it exists, there is porn of it.

Ethical Conundrums: Gerhard Reinke’s Wanderlust and Las Hurdes

You probably never saw it, but it was a funny show with something and nothing to say. Back in 2003, Jimmy Kimmel’s Jackhole Productions produced six episodes of a show for Comedy Central called Gerhard Reinke’s Wanderlust. Each week, its fictional German host (played by American Adam Gardner) toured some part of the world – usually some part of the third world. Gerhard Reinke was a hapless traveler. He succumbed to some sort of travel-related malady in nearly every show – from bugbites to embarrassing erections.

When a situation demanded caution, he was gullible. Where compassion would have been appropriate, he was shrewd. After cheerily explaining that, “Bolivia’s economic crisis makes it one of the cheapest places in the world!,” he rather cruelly haggles over seemingly low-value currency with a presumably poor woman selling a llama fetus in La Paz’s “witch’s market.”

Though his travel skills were severely lacking, Reinke fared little better as a television host. On the easier side of the show’s humor, his thick German accent led to some cheap laughs when he visited “Wenice Beach” California. But his challenged hosting skills could demonstrate a sharper satirical edge as well. As evidenced in his celebration of Bolivia’s troubled economy, his narration rarely matched the tone demanded of a situation. While Gerhard cheerily described the miseries caused by international economic inequality, he was deadly serious when dealing with insubstantial maladies or undertaking any of his projects (like searching for Bigfoot or writing erotic fiction). Fundamentally, these moments of tonal contradiction evidenced a self-centeredness that appears to trouble the ethical positions of both the tourist and media consumer in a global economy. At the same time, it is a comedy and as such it is better at critiquing than offering solutions.

In this way, it is reminiscent of Luis Buñuel’s 1933 film Las Hurdes: Tierra Sin Pan (English: Land Without Bread). This film, also a mockumentary travelogue, offers its audience a view of an economically disadvantaged peasants living in the Hurdes region of Spain. While not as obviously comic as Wanderlust, Buñuel’s humor relies on a similar tonal mismatch. The narrator of this film remains disinterested and at times even amused as he describes and comments on the terrible conditions of the film’s subjects. Gerhard’s relationship to his audience is a bit more complicated. Unlike the disembodied “voice-of-God” narrator of Las Hurdes, Gerhard is a transparently flawed host. Laughing at Buñuel’s narrator feels somewhat like laughing at myself. The laughter directed at Reinke is less reflexive – it is directed at the over-confident “German” doofus. Still, laughing at Gerhard is not entirely unproductive. Although he does not implicate the viewer as directly as does Las Hurdes‘ narrator, we still must accept Reinke’s position as viewer surrogate in our relationship to this media text. And unlike in Buñuel’s film, we here see the figure of the tourist in some of its worst excesses. This kind of misery-tourism might be subtly suggested in Las Hurdes, but it is a major and explicit theme in Gerhard Reinke’s Wanderlust.

In perhaps its most obviously comic moment, Las Hurdes shows a goat scaling a rocky cliff. “One eats goat meat only when one of the animals is killed accidentally,” explains the narrator. “This happens sometimes when the hills are steep and there are loose stones on the footpath.” A puff of smoke billows in from offscreen and the goat falls. The narrator has lied to us. The goat did not trip – it was shot. While the whole film seems to ask what the viewer’s responsibility might be towards disadvantaged Others, this moment suspends those questions to ask more fundamentally what and how we actually know about the people and things we witness from the other side of the screen.

Similarly, though with more broadly comic strokes, Wanderlust mixes a heaping dose of falsity into its documentary explorations. Every episode devolves into some kind of fictional narrative as Gerhard joins a Marxist revolutionary group or struggles with an affliction known as “pee shyness.” So although a good part of both texts ask us to think about our relationship to other human beings, these moments undercut their moral imperative by asking how we can even know the experiences of others in these distant places. There seems to be on the one hand an imperative to act based on the documentary evidence of human suffering. But there is also a more radical proposition that we can’t trust texts like the ones we are watching, which undercuts the moral certainty of the first proposition.

So which is the more powerful argument? Neither Las Hurdes‘s narrator nor Gerhard Reinke (or Luis Buñuel or Josh Gardner) will tell us. Despite the apparent intended message of Las Hurdes, it offers a message of resignation in the face of suffering. While the concern with other humans seems the more ethically defensible position, the proposition that these media themselves are untrustworthy denies such neat moralism. Disturbingly, the warnings against being overly trusting of such appeals seems to be the more powerful message here. So don’t worry too much about the Hurdes or the poor woman selling the llama fetus: they might as well be fictional.

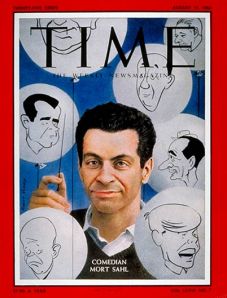

Mort Sahl: Conspiracy Theorist

In 1960, Time magazine placed Mort Sahl on its cover, declaring him, “the patriarch of a new school of comedians” that included Mike Nichols, Elaine May, Lenny Bruce, and Jonathan Winters.

His brand of erudite political humor had made him the comic of the moment – and this was a fertile moment for American comedy. While careful to maintain his image as an iconoclast, Sahl nevertheless went to work writing jokes for the 1960 Kennedy presidential campaign. However, his comedy remained critical of Kennedy both during and after the election, at least until late 1963.

There were signs that Sahl’s popularity began to wane due to broad trends resulting from decreased demand for political humor and sharp satire after Kennedy’s death. However, most narratives of Sahl’s career, including his own autobiography, point to a more important factor in his retreat from the spotlight: his becoming a Kennedy conspiracy theorist. As part of his work on a syndicated television program, Sahl traveled to meet Jim Garrison (the subject of Oliver Stone’s JFK) who by 1967 claimed to have solved the mystery of Kennedy’s shooting. The CIA, by Garrison’s account, killed the president because of his efforts at ending the Cold War and weakening the CIA. Garrison deputized Sahl who, funded from his own pocket, delved into the investigation. These years proved particularly difficult for Sahl. Not only was he spending time and money investigating instead of performing, his reputation and performances as a paranoiac prevented bookings and disappointed audiences. Of course, by Sahl’s probably not entirely false account, his career was torpedoed by those who disagreed with or wanted to silence his opinions on this matter, including the powerful in the entertainment and political world.

When Sahl performed, his routines increasingly focused on the assassination. Audiences grew tired of his repeated performances reading word-for-word from The Warren Commission Report and staging sketches using directly-quoted government testimony. Holding the comic up as a prototypical post-Kennedy conspiracy theorist while explaining his downfall, John Leonard in 1978 wrote in The New York Times,

He went strange after the assassination of John Kennedy. And in that sense, too, he was a stand-in for the children of the 1950’s. It suddenly seemed that we were no longer the pampered children of the Enlightenment, getting better every day. Until that particular assassination, there was a European way of thinking about conspiracies (there has to be a conspiracy, because it would absolve the rest of us of guilt) and an American way (there can’t be a conspiracy, because then there’s no one to take the rap). Mort Sahl went European all the way into the swamp wevers of the mind of New Orleans Attorney Jim Garrison.

And the talk shows stopped wanting to hear him go on about the grassy knoll, the two autopsies, the washed-out limousine, Lee Harvey Oswald’s marksmanship, Jack Ruby’s friends. He wasn’t funny. He was also, eventually, unemployed, and bitter, as he made clear in his memoir, “Heartland” [sic].

Although vindicated to some extent by the eventual public mistrust of The Warren Commission Report and more provable conspiracies like Watergate, Mort Sahl’s career never recovered.

Sahl is not the only humorist invested in conspiracy theories. Dick Gregory’s commitment to civil rights and other social justice movements led him down similar paths questioning historical orthodoxy. In more recent years, comics like Dave Chappelle have played around with similar notions while shows including The Boondocks, King of the Hill,and South Park have all taken a turn at conspiracy theory-themed narratives. While different comics and shows are differently invested in these themes, it suggests a commonality regarding the political humorists’ mindset. If comedy’s cultural value arises in part from questioning and straining conventional logic, it only makes sense that it would question and strain conventional history as well.

(c) 2013, Phil Scepanski

Watching TV Scramble: Editing Jokes After the Fact

As I watched last night’s Family Guy, my local Chicago station’s news teaser informed me of an unfolding tragedy to our West. Tornadoes were hitting parts of the Midwest and they were heading our way. As the second episode began, one character, Stewie, requested that they watch The Weather Channel because, “there are tornadoes in the Midwest and I like watching poor people scramble to save what little they have.” For those who didn’t initially notice it, the presence of an onscreen weather warning made the juxtaposition explicit.

This was not the first instance of Family Guy inadvertently finding extra sickness as their jokes took on new substance in relation to current events. The March 17 episode, “Turban Cowboy,” showed a character, Peter, drunk-driving his way through a crowd of runners to win the Boston Marathon. Later in the same episode, Peter unwittingly becomes involved with a terrorist organization, which leads to a gag in which he repeatedly, albeit accidentally, detonates bombs with his cell phone. After the attacks at the Boston Marathon less than a month later, these clips gained a lot of traction on the internet and Fox pulled the episode from its official internet sites and, at least for now, from future airing as reruns.

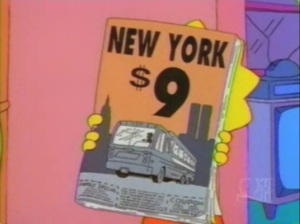

Over at Splitsider, Joshua Kurp lists similar situations in response to 9/11 with episodes of The Simpsons, Rocko’s Modern Life, Sex and the City, Friends, Married. . .With Children, and Spongebob Squarepants.

In these cases, where jokes get cut or entire episodes disappear from reruns, we witness a fascinating indicator of humor and television’s temporality in relation to more serious events in the “real world.” The inadvertent nature of these juxtapositions create a kind of dramatic irony that adds an extra element of humor to these episodes. But they also indicate interesting changes in what is considered to be acceptable discourse. Kurp’s article claims – and DVD commentary by writers backs him up – that many syndication markets pulled the 1997 Simpsons episode in which Homer visits New York and has a particularly hard time in the shadows of the Twin Towers. Even after its return, at least one joke remains edited for the sake of sensitivity. One man informs Homer that, “They put all the jerks in Tower One.” Entirely inoffensive in its original context, the concept that any “jerks” (aside from the hijackers) might have died on 9/11 has apparently become unfathomable. Of course, to say it out loud makes that idea sound ludicrous, but the construct that dichotomizes cowards and heroes in the wake of such events is a powerful tool of both psychological comfort and ideological reinforcement. That a joke made to the contrary – even one made in 1997 – cannot question that logic is apparently too radical for syndication.

For humor and media scholars, these prove especially interesting cases for thinking about the temporality of both. While often theorized as an essentially live medium, television in these cases seems to straddle a line between past-ness and present-ness as it shows documents from the past, but edits appear to deny their status as historical documents. The same might be argued of racist, sexist, or any other troubling -ist humor in other texts, but these are not judgments based on universal ethical or moral values. Instead, they reflect a fundamentally ahistorical reading of television comedy in relation to privileged instances of ideology.

(c) 2103, Phil Scepanski

The Mad Mad Mad Mad Comedy of Jonathan Winters

I’m generally not given to hagiography in the wake of celebrity death. Still, hearing about Jonathan Winters’  dying touched me. This is likely in part because he looked so much like my grandfather, but also because I really liked Jonathan Winters. I remember fighting to catch my breath watching the short-lived sitcom Davis Rules as a kid. If memory serves, Winters’ had advised his grandchildren that to dissuade people from sitting near you at the movies, you should stick Raisinets to your face and cry, “fungi fever.” It was the delivery that sold it. The Emmy voters agreed as he won Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Comedy Series for the sitcom that could not make it past 29 episodes.

dying touched me. This is likely in part because he looked so much like my grandfather, but also because I really liked Jonathan Winters. I remember fighting to catch my breath watching the short-lived sitcom Davis Rules as a kid. If memory serves, Winters’ had advised his grandchildren that to dissuade people from sitting near you at the movies, you should stick Raisinets to your face and cry, “fungi fever.” It was the delivery that sold it. The Emmy voters agreed as he won Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Comedy Series for the sitcom that could not make it past 29 episodes.

My favorite Winters moment comes from a less esoteric source: It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World. This film contains, with all due respect to the Stooges and Chris Farley, my favorite three and a half minutes of anarchic, destructive physical comedy in a visual medium.

In this scene, Winters’ captors condescend as they explain that he is about to be shipped off to a mental hospital. In fact, Jonathan Winters had, by this film’s 1963 release, spent time in what he referred to on his 1960 LP The Wonderful World of Jonathan Winters as “the zoo.” Mental illness haunted Winters throughout his life. Despite the challenges and stigmas associated with these issues, he had broken through by the 1960s. In an era where comedy engaging in profanity, political commentary, or innovation ran the risk of being called “sick,” Winters embodied the mentally ill connotations of the term – acting out the manic half of his real-life bipolar disorder with stream-of-consciousness routines that I trust the surrealists (along with a coked-up Robin Williams) appreciated. Introducing Winters on The Jack Paar Program in 1964, Paar made sly reference to Winters’ mental illness explaining, “If Jonathan Winters is ever accused of anything, he’s got the perfect alibi. He was someone else at the time.”

While stunt doubles seemingly accomplish much of the physical comedy in the above scene from It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World, Winters’ continual attempts to calm the situation even as the gas station lays in rubble, along with his voiceover’s underplayed threats (“uh huh, there you are”) speak to his particular angle on sick comedy in mid-century. Winters lay at one end of a spectrum occupied at the other end with the likes of Bob Newhart. If Newhart (in his routines and on his sitcom as a psychologist) calmly played sane while those around him demonstrated the world’s insanity, Winters was the comic driven to mania and dissociative disorder by an overly buttoned-down world. But Jonathan Winters’ discontent would not be repressed by civilization. The joy of his comedy then was that he broke from the attempt at control, tearing out of and tearing down the proverbial electric tape and gas station that could not contain him.

(c) 2013, Phil Scepanski

Meta-Racist Airplane Jokes: The Foolish Audience and Didactic Humor

What do you call a black man flying an airplane? A pilot, you racist.

It is not complicated, but this meta-joke activates a complex meaning-making process. The setup connotes a genre of racist jokes, inviting the listener to imagine what possible stereotype about black men will fulfill the question in an unexpected way. The answer of “a pilot” is surprising precisely because it is unsurprising. If orthodox racist jokes tend to fulfill psychoanalytic models in their ability to express otherwise forbidden acts of expression, this joke plays more on the surprise theory by inverting dramatic irony to pleasurably expose the listener’s own prejudices and ideally creating some positive self-awareness in the process.

Dramatic irony occurs when the audience knows something a fictional character does not. I read the above joke as an inversion of that particular form because the “audience” for this joke is the one kept in ignorance until the moment of the punchline. Though not necessarily given to social justice for every listener, this joke is ideally didactic in that it makes a pleasurable game of exposing the listener’s prejudices. Neither this form of humor nor its seeming aspirations to a small lesson in social justice are limited to verbal jokes though. To illustrate these points, I turn to an example that uses visual and verbal language to similar ends with relevant contemporary implications.

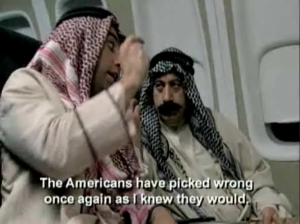

In 2003, Chappelle’s Show aired a sketch titled “Diversity in First Class.” Although given to left-leaning rhetoric, Chappelle’s Show was not above admissions of prejudice in certain situations. Taking place on a commercial airplane, the camera pans past a pair of men coded as Middle Easterners by their clothing and language. Engaged in a heated discussion, their performance displays aggression in both speech and hand motions. Clearly meant to invoke the image of Islamic terrorists, its original airdate less than 18 months after 9/11 framed its reading in terms of that national trauma. Subtitles further encourage reading the pair as a threat, adding verbal cues to the visual language connoting terrorism. But as the men continue, the subtitles reveal the true nature of their conversation.

By leading his expectations in one direction before dashing them, this contradiction between image and reality makes the viewer foolish. Not only that, but these Others discuss a well-known bit of Western pop culture, making their conversation familiar and laughably non-threatening.