Mort Sahl: Conspiracy Theorist

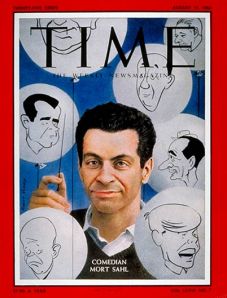

In 1960, Time magazine placed Mort Sahl on its cover, declaring him, “the patriarch of a new school of comedians” that included Mike Nichols, Elaine May, Lenny Bruce, and Jonathan Winters.

His brand of erudite political humor had made him the comic of the moment – and this was a fertile moment for American comedy. While careful to maintain his image as an iconoclast, Sahl nevertheless went to work writing jokes for the 1960 Kennedy presidential campaign. However, his comedy remained critical of Kennedy both during and after the election, at least until late 1963.

There were signs that Sahl’s popularity began to wane due to broad trends resulting from decreased demand for political humor and sharp satire after Kennedy’s death. However, most narratives of Sahl’s career, including his own autobiography, point to a more important factor in his retreat from the spotlight: his becoming a Kennedy conspiracy theorist. As part of his work on a syndicated television program, Sahl traveled to meet Jim Garrison (the subject of Oliver Stone’s JFK) who by 1967 claimed to have solved the mystery of Kennedy’s shooting. The CIA, by Garrison’s account, killed the president because of his efforts at ending the Cold War and weakening the CIA. Garrison deputized Sahl who, funded from his own pocket, delved into the investigation. These years proved particularly difficult for Sahl. Not only was he spending time and money investigating instead of performing, his reputation and performances as a paranoiac prevented bookings and disappointed audiences. Of course, by Sahl’s probably not entirely false account, his career was torpedoed by those who disagreed with or wanted to silence his opinions on this matter, including the powerful in the entertainment and political world.

When Sahl performed, his routines increasingly focused on the assassination. Audiences grew tired of his repeated performances reading word-for-word from The Warren Commission Report and staging sketches using directly-quoted government testimony. Holding the comic up as a prototypical post-Kennedy conspiracy theorist while explaining his downfall, John Leonard in 1978 wrote in The New York Times,

He went strange after the assassination of John Kennedy. And in that sense, too, he was a stand-in for the children of the 1950’s. It suddenly seemed that we were no longer the pampered children of the Enlightenment, getting better every day. Until that particular assassination, there was a European way of thinking about conspiracies (there has to be a conspiracy, because it would absolve the rest of us of guilt) and an American way (there can’t be a conspiracy, because then there’s no one to take the rap). Mort Sahl went European all the way into the swamp wevers of the mind of New Orleans Attorney Jim Garrison.

And the talk shows stopped wanting to hear him go on about the grassy knoll, the two autopsies, the washed-out limousine, Lee Harvey Oswald’s marksmanship, Jack Ruby’s friends. He wasn’t funny. He was also, eventually, unemployed, and bitter, as he made clear in his memoir, “Heartland” [sic].

Although vindicated to some extent by the eventual public mistrust of The Warren Commission Report and more provable conspiracies like Watergate, Mort Sahl’s career never recovered.

Sahl is not the only humorist invested in conspiracy theories. Dick Gregory’s commitment to civil rights and other social justice movements led him down similar paths questioning historical orthodoxy. In more recent years, comics like Dave Chappelle have played around with similar notions while shows including The Boondocks, King of the Hill,and South Park have all taken a turn at conspiracy theory-themed narratives. While different comics and shows are differently invested in these themes, it suggests a commonality regarding the political humorists’ mindset. If comedy’s cultural value arises in part from questioning and straining conventional logic, it only makes sense that it would question and strain conventional history as well.

(c) 2013, Phil Scepanski

REMEMBERING DICK GREGORY

Sam Sackett

I saw Dick Gregory once, and I want to commemorate that occasion while he is still alive. I hope he reads this.

Before I enter upon my narration, let me introduce myself and set the stage.

My mother did not tell me I was Jewish until I was 46 years old. I was not raised Jewish in any way. We ate pork and ham at home. I had never been inside a temple or synagogue. And yet I was thoroughly familiar with Jewish family life because I listened to the radio, especially the Jewish comedians like George Jessel (“Hello, Mama, this is Georgy”), Eddy Cantor, and Minerva Pius, who was Mrs. Nussbaum in Fred Allen’s Alley (“You were expecting maybe Greta Garfinkel?”). I don’t count Jack Benny; he was a comedian who happened to be Jewish, not a Jewish comedian. Gertrude Berg was not a comedian, but her portrayal of Jewish life in the soap opera The Goldbergs certainly had its effect. There were others whose names I have forgotten, but because of radio comedians I became thoroughly familiar with what English sounded like with a Yiddish accent. And long before I was 46 I was keenly aware both of antisemitism among the kids I went to school with and of the way in which Jewish comedians were gradually making Jews more familiar and hence more acceptable to goyim.

Now that I’ve introduced myself, let me set the stage. After the Civil War, the United States Army set up military installations throughout the western U.S. with the purpose of protecting settlers moving west from what we now know are Native Americans but were then called Indians. Many of the troops assigned to these forts were what were known as “buffalo soldiers” – freed slaves. After all, during the war the Union army had made use of “colored” troops – not, of course, integrated into white units, but as separate but equal units – and these soldiers had acquitted themselves well in battle. Around the outposts towns grew up, and as time went on some of them became almost civilized. The state college where I was teaching was located in such a town, and buffalo soldiers had served in the adjacent fort.