Risk vs. Reward: When are Jokes too Risky?

The “reward” for humor is obvious—the payback for the humorist is when the audience laughs. The payback for the audience is also the laugh—it brightens an otherwise difficult day, relaxes as the laughter happens, and lets an audience leave the show, piece, or joke a bit happier than they were before. However, being the humorist is not without risk. What induces laughter in one person can offend another—this has been the legacy of humor since ancient times. Thus, those to whom humor is a profession must walk a fine line between taking a risk and reaping a reward.

Mark Twain found this out during his Whittier Birthday speech, delivered on 17 December 1877. In the speech, he told a story about four drunken miners whom he described such that without doubt, the characters referred to Whittier, the guest of honor, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Oliver Wendell Holmes—often described as the “Boston Brahmins.” The joke fell through, and Twain was embarrassed by the reactions of the audience and the public when the speeches were published in the Boston Globe the following day. The Cincinnati Commercial asserted that Twain “lacked the instincts of a gentleman,” and even in the less conservative West the Rocky Mountain News called the speech “offensive to every intelligent reader.” Twain published an abject apology a week later, and even after 25 years the criticism still stung. Sometimes parodying a cultural icon is just too risky.

Twain’s 1877 faux pas illustrates just how difficult it is to gauge an audience’s reaction to material that the artist considers humorous. At this year’s Modern Language Association in Vancouver, three fine presenters delivered papers on the topic of “Comic Dimensions and Variety of Risk.” Jennifer Santos read her paper on Holocaust jokes in Epstein’s King of the Jews, Roberta Wolfson presented on the Canadian television show, Little Mosque on the Prairie, and John Lowe read his essay on Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint. Each presenter focused the talk on reception of the humor and the acceptable amount of risk a comedian or humorist can take and still reap the “reward” of laughter. Aside from hearing three wonderful examinations on a variety of humorous subjects, this panel generated discussion of the broader issue of risk versus reward every purveyor of humor must determine for any written or spoken performance. Who is allowed to joke about possibly sensitive events? From whom are we willing to accept a joke that takes a risk of offending?

Calling All Social Critics and Comedians!

As I finalize my selections for a course on American Counterculture from the 1960s to present day, I slyly grin at the allotment of time dedicated to the late great cultural rebel George Carlin. The truth is, I miss him. I never had the opportunity to meet him or see a live show, but I’ve watched and read so much on, about, for, and from Carlin that he feels like an ostracized yet beloved great uncle. As with Lenny Bruce before him, Carlin’s work demonstrated the honesty, passion, and brilliance of his predecessor. A look at a compilation of The Best of George Carlin proves this:

From the 1970s until his death in 2008, the self-proclaimed lover of language elucidated his countercultural propensities in albums such as FM & AM and Class Clown – the latter containing what would later become know as his infamous “Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television” shtick. His jokes pertaining to religion, politics, drugs, war, government, human interactions, and relationships were legendary and established Carlin’s unapologetic career in comedy. Through humor, he begged audiences in a 2004 CNN interview to “first of all, question everything you read or hear or see or are told . . . [a]nd try to see the world for what it actually is, as opposed to what someone or some company or some organization or some government is trying to represent it as, or present it as, however they’ve mislabeled it or dressed it up or told you.”

As social critic and thinker, Carlin used humor as his vehicle – he did not mean for audiences to be purely and purposelessly entertained. I use Carlin to introduce students to humor as counterculture but also to show how to clearly support claims with evidence, how an informed participant is better than an unenlightened observer, speaker, and writer. His genius – as well as his comedic charisma – will hopefully illustrate the power of passion and awareness in a course dedicated to both.

Noticeably absent from my selections are women who were/are social critics and comedians. After watching Women Who Kill, a 2013 Showtime special highlighting Amy Schumer, Rachel Feinstein, Nikki Glaser, and Marina Franklin, I couldn’t help but wonder if what was presented in this 59 minute show was the best I could find. I patiently watched each comedian present her ideas on dating, abuse, children, weight, and fashion with clever language and verbal trickery, but finished the show having laughed, felt, or thought very little.

I realize the pressure of the ‘Carlin comparison’ – no human, male or female, can match the genius of George, but the sustenance from his shows, and the shows of the likes of Bruce and Hicks, seems to be deficient in modern comedy, especially that showcased by females. Many comedians use a new sensationalism – similarly to what the modern world now relies on for entertainment purposes – which seems more grating than gift. In an article titled “Laughter the Best Medicine: Muslim Comedians and Social Criticism in Post-9/11 America,” author Amarnath Amarasingam explores the role of Muslim standup comedians who challenge misperceptions about culture, religion, and relationships and could do well to be defined under Gramsci’s classification of “organic intellectuals” (467). Comedians such as Azhar Usman and Maz Jobrani challenge societal expectations and push the limitations of previously held thought. Through discussions of social criticism, their humor is welcomed among the drivel so disliked by many, including Carlin himself.

© 2014 Tara Friedman

Watching TV Scramble: Editing Jokes After the Fact

As I watched last night’s Family Guy, my local Chicago station’s news teaser informed me of an unfolding tragedy to our West. Tornadoes were hitting parts of the Midwest and they were heading our way. As the second episode began, one character, Stewie, requested that they watch The Weather Channel because, “there are tornadoes in the Midwest and I like watching poor people scramble to save what little they have.” For those who didn’t initially notice it, the presence of an onscreen weather warning made the juxtaposition explicit.

This was not the first instance of Family Guy inadvertently finding extra sickness as their jokes took on new substance in relation to current events. The March 17 episode, “Turban Cowboy,” showed a character, Peter, drunk-driving his way through a crowd of runners to win the Boston Marathon. Later in the same episode, Peter unwittingly becomes involved with a terrorist organization, which leads to a gag in which he repeatedly, albeit accidentally, detonates bombs with his cell phone. After the attacks at the Boston Marathon less than a month later, these clips gained a lot of traction on the internet and Fox pulled the episode from its official internet sites and, at least for now, from future airing as reruns.

Over at Splitsider, Joshua Kurp lists similar situations in response to 9/11 with episodes of The Simpsons, Rocko’s Modern Life, Sex and the City, Friends, Married. . .With Children, and Spongebob Squarepants.

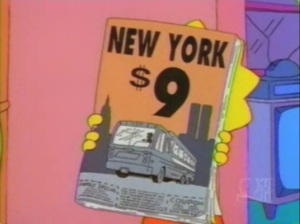

In these cases, where jokes get cut or entire episodes disappear from reruns, we witness a fascinating indicator of humor and television’s temporality in relation to more serious events in the “real world.” The inadvertent nature of these juxtapositions create a kind of dramatic irony that adds an extra element of humor to these episodes. But they also indicate interesting changes in what is considered to be acceptable discourse. Kurp’s article claims – and DVD commentary by writers backs him up – that many syndication markets pulled the 1997 Simpsons episode in which Homer visits New York and has a particularly hard time in the shadows of the Twin Towers. Even after its return, at least one joke remains edited for the sake of sensitivity. One man informs Homer that, “They put all the jerks in Tower One.” Entirely inoffensive in its original context, the concept that any “jerks” (aside from the hijackers) might have died on 9/11 has apparently become unfathomable. Of course, to say it out loud makes that idea sound ludicrous, but the construct that dichotomizes cowards and heroes in the wake of such events is a powerful tool of both psychological comfort and ideological reinforcement. That a joke made to the contrary – even one made in 1997 – cannot question that logic is apparently too radical for syndication.

For humor and media scholars, these prove especially interesting cases for thinking about the temporality of both. While often theorized as an essentially live medium, television in these cases seems to straddle a line between past-ness and present-ness as it shows documents from the past, but edits appear to deny their status as historical documents. The same might be argued of racist, sexist, or any other troubling -ist humor in other texts, but these are not judgments based on universal ethical or moral values. Instead, they reflect a fundamentally ahistorical reading of television comedy in relation to privileged instances of ideology.

(c) 2103, Phil Scepanski