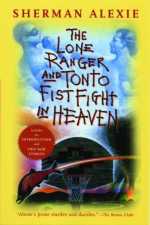

Even before I got cancer, my favorite kind of humor was the type you might call “painfully funny.” One of my favorite short stories, to read and to teach, is “The Approximate Size of My Favorite Tumor,” by Sherman Alexie. Jimmy Many Horses has spent his life “laughing to keep from crying,” as the old song goes, telling jokes to gain some illusion of control in bad situations, to claim his humanity in the midst of chaos, death, or inhumanity. Problem is, he can’t stop telling jokes, even when telling his wife about his visit to the doctor, giving him his diagnosis of terminal cancer:

“I told her the doctor showed me my X-rays and my favorite tumor was just about the size of a baseball, shaped like one, too. Even had stitch marks.”

“You’re full of shit.”

“No, really. I told her to call me Babe Ruth. Or Roger Maris. Maybe even Hank Aaron ’cause there must have been about 755 damn tumors inside me. Then I told her I was going to Cooperstown and sit right down in the lobby of the Hall of Fame. Make myself a new exhibit, you know? Pin my X-rays to my chest and point out the tumors What a dedicated baseball fan! What a sacrifice for the national pastime!”

While Jimmy’s wife needs him to be serious for a moment, to give her a chance to process her shock and grief, and while she might even have been willing to join him in jokes to cope later — Jimmy cannot stop and give her that time, even when she tells him she’ll leave him if he says one more funny thing. But even in the midst of his fury at this unwanted and useless “sacrifice” that has been pressed upon him, Jimmy’s joke is brilliant, both inside and outside the context of the story.

While Jimmy’s wife needs him to be serious for a moment, to give her a chance to process her shock and grief, and while she might even have been willing to join him in jokes to cope later — Jimmy cannot stop and give her that time, even when she tells him she’ll leave him if he says one more funny thing. But even in the midst of his fury at this unwanted and useless “sacrifice” that has been pressed upon him, Jimmy’s joke is brilliant, both inside and outside the context of the story.

The historical allusions to baseball and Hank Aaron’s supplanting of Babe Ruth’s home-run record (with his 755 career home runs) raise issues about the racism that plays a low-key but omnipresent role in the rest of the story. Even in 1973, when Aaron was getting close to breaking Ruth’s record, he received about 930,000 letters, the majority of them death threats or wishes that he would die, full of dehumanizing epithets: “You black animal, I hope you never live long enough to hit more home runs than the great Babe Ruth.” Another letter that has been widely quoted wishes on Aaron a disease primarily connected with Africa and her descendants: “Dear Hank Aaron, How about some sickle cell anemia, Hank?”

But cancer, as Jimmy reminds us, does not discriminate; it is not a respecter of race, class, or power. Cancer, like humor, is an equal opportunity offender. And cancer has become almost like a national pastime. You can’t go anywhere without running into those damned pink ribbons and pricey pink items commodifying death and infantilizing the very personal, protracted, and agonizing fight to survive against breast cancer, a phenomenon some angry breast-cancer survivors have labeled “pinkwashing” — all purchased with the best of intentions and the hope to find a cure. But that support ironically creates a sense of audience, of fandom and voyeurism, the pink ribbons becoming our admission tickets to the new national pastime. Cancer itself is like a bad joke that just won’t quit.

To me, it is this kind of humor that reminds us of who we are, how little we actually control, and why it all matters anyway. Robert Heinlein once wrote, “We laugh because it hurts, because it is the only thing that will make it stop hurting,” but I would have to disagree. Humor doesn’t make the pain stop. It only makes it bearable. Taking something in life that is chaotic and seems to have no boundaries and then finding the humor in it allows you to give it boundaries — to exercise the very human need to choose our own point of beginning and ending. Making a narrative gives us a sense of control –control over the story, anyway, and the power to spin it in a direction that momentarily puts us in the driver’s seat, and creates a sense of community, as we take our audience along for the ride.

Tig Notaro, a stand-up comedian, took the driver’s seat in August 2012, when she got up on stage and opened her set:

Hello. Good evening and hello. How are you? Is everyone having a good time? I have cancer. How are you? . . . just diagnosed . . . .

The laughter is scattered in the beginning, the audience uncertain of where Notaro is going or whether she is serious and if she is, whether they should laugh — after all, this is a stand-up comedy show. But as the routine progresses — ironically as Notaro reveals that she is, indeed, serious — the laughter gets fuller, more prolonged. And frankly, the set is hilarious and tragic, deep laughter with tears running freely.

But to me, the funniest and the most horrible moment in the set comes when Notaro announces that she’s ready to close with one of her usual, cheery, prepared routines on an experience we all share: getting stuck in traffic. One member of the audience shouts out — no, this is great, don’t stop. Caught up in the emotion, the sharing, the laughter, the audience wants her to continue, needs her to continue. The comedian actually finds herself apologizing for having no more tragedy to share as the laughter escalates. A powerful and disturbing moment.

The intimacy is real and yet distant, the “sacrifice” of the “fans” both consonant and dissonant with the sacrifice of the comedian. While most people in the audience probably have some experience with cancer, and some might even be in the midst of their own battles, in this dynamic their experience is mute and distant. They will go home with the memory of this night, and back to their own lives, distant from her struggle. But she will go home to continue living the “joke,” home to chemotherapy, mastectomy, and agonizing uncertainty that will drag on for years. And she will get stuck in traffic.

It is this surreal quality of the normal intertwined with the extremes of cancer that Anthony Griffith addresses so hilariously and poignantly in his “The Best of Times, the Worst of Times”. He tells the incredible story of the year he reached the pivotal moment of his career — being invited to perform on The Tonight Show — at the same time he was dealing with his child’s protracted and agonizing death from brain cancer. The disconnection between the light and breezy routines that were expected of him and the rage and despair and grief that still boils within him is heartbreaking. His anguished barbs about the cost of keeping up that mask are hilarious and gut wrenching. His personal mantra — telling himself to just “Man up, Nigger” and get on with life, because black people don’t see mental support professionals — is haunting, yet oddly empowering. While my own wariness of the mental health community is class-based and personal rather than racially based, during my own cancer struggle I found myself often saying, “Woman up, Bitch. Do it.”

Fierce laughter and the tears. We’re all full of shit. And we all get stuck in traffic.

© Sharon McCoy 4 December 2012

[…] Painfully Funny (humorinamerica.wordpress.com) […]

[…] dreary variety, it is sometimes unpleasant to be cheerful. Although as Sharon McCoy reminded us, painful humor is often the best kind (Matt Daube discussed another response in relation to recent, horrific […]

[…] living in a germ-filled world when you’re immuno-compromised, or even if you’re not) Painfully Funny (about the cancer humor of Sherman Alexie, Tig Notaro, and Anthony Griffith, and how the laughter […]

[…] Birthday, Max Shulman“; or “Happy Birthday, Muhammed Ali“; or my “Painfully Funny“; “Poetry Corner–Paul Laurence Dunbar: Changing the Joke to Slip the […]